Sometimes it takes a while to convince others of your opinion. For Professor of Anthropology Fred Smith, it took nearly 20 years for science to come around to his point of view.

Smith, a human paleontologist who studies the form and structure of Neandertals and early modern humans, has long been saying that modern humans have more than a touch of Neandertal in them, genetically and anatomically speaking. Turns out, he was right.

Much is known about the Neandertals. Once stereotyped as a hulking, dull-witted group that died out around 30,000 years ago, scientists now study them as skilled tool-makers who were well-adapted to the cold weather of Europe in the Pleistocene era.

“Speaking as paleontologists, we have a pretty good handle on Neandertals,” said Smith, who has been studying their fossil remains for more than 40 years.

“Physically, Neandertals may be gone, but genetically, they are still with us.”

With his work taking him to almost every known Neandertal site in Europe and Western Asia, Smith has examined about 12,000 bones from as many as 400 individuals. A majority of his published works are grounded in three of the most important Neandertal sites – Krapina in Croatia, where early Neandertals lived, Vindija, also in Croatia, home to later Neandertals, and the original Neandertal discovery site in Germany.

Though scientists know much from the fossils they uncover, the question has always been what the relationship was between Neandertals and the early modern humans who replaced them in Europe. The answer in the 1970s and ’80s resulted in two opposing views.

One idea, known as the Multi-Regional Model, was that Neandertals evolved into humans, or were at least an ancestor of modern humans. The other idea, known as the Recent African Origin Model, proposed that modern humans came up from Africa and replaced Neandertals, wiping them out completely.

Advanced dating techniques and other information has rendered the Multi-Regional Model highly improbable. “It became pretty evident that Neandertals were in Europe until pretty late,” overlapping with early humans, said Smith. So most scientists accepted the Recent African Origin Model. But something didn’t sit right with Smith and others.

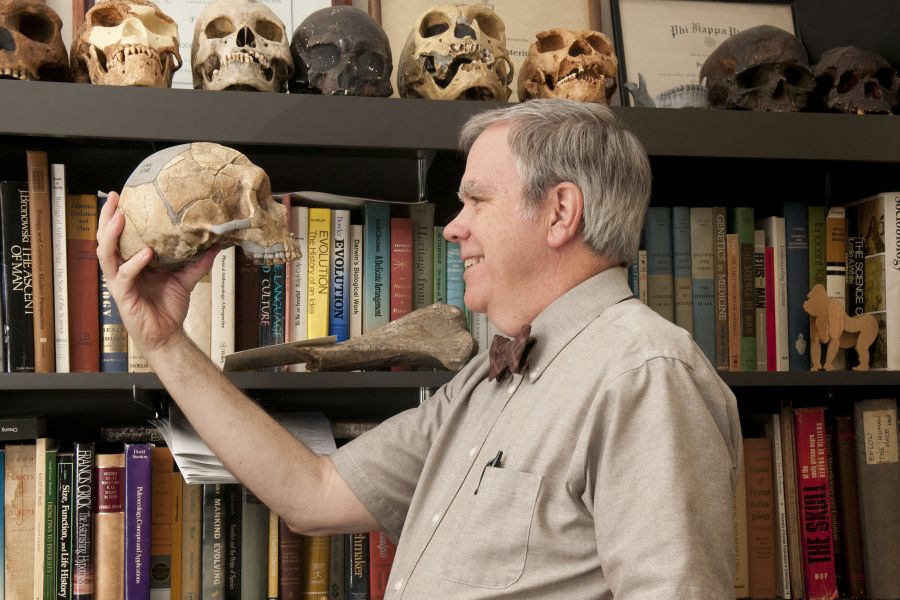

“Early modern Europeans have a high frequency of a projection in the back of the skull called an occipital bun,” said Smith, holding the cast of a young man’s skull who lived thousands of years ago. “Now in Neandertals, there is that same projection.” Smith reached out for a different cast, this time with a much flatter forehead, but with the same pronounced bump in the back of the skull. “If you look at early modern humans in Africa or western Asia, they don’t have these buns. I think the most likely explanation is that this shows some input from Neandertals into that modern human gene pool.” Occipital buns are only one of a series of anatomical details that Smith believes modern Europeans derived from Neandertals.

Smith developed his theory, a variation of the Recent African Origin Model, which he called the Assimilation Model, in the late 1980s.

“The Assimilation Model argues that yes, modern humans do come out of Africa, but as they move into these areas where Neandertals live – like western Asia and Europe – the population dynamics of their interaction are very complex, and some Neandertal elements are assimilated into the ultimately larger, human gene pool.”

When he proposed the idea in the late 1980s, the Assimilation Model was either ignored or rejected. “I got some attention, and that was fine with me,” said Smith. “I’m primarily a university teacher, and I didn’t have time to go around selling the idea. Occasionally it would bother me, but I’m not very pushy and was not out there promoting it all the time.”

It was a small thing that made the scientific community turn its head to Smith’s theories. In fact, several billion strands of small things, known as DNA.

In the late 1990s, scientists began to study the more simplistic mitochondrial DNA, but those showed no conclusive genetic evidence of Neandertals in the early modern bones analyzed. “At first, it didn’t look good for the Assimilation Model,” said Smith.

Then, in 2006 and later in 2010, the Max Planck Institute published studies of much more detailed nuclear DNA samples. The results showed that somewhere between 1 and 4 percent of modern, living, Eurasian genes stem from Neandertals.

“It’s a relatively small, but not insignificant amount, which is exactly what the Assimilation Model said,” noted Smith. “Physically, Neandertals may be gone, but genetically, they are still with us.”

The change in opinion hasn’t changed Smith, who has been writing, publishing and teaching constantly over his 40-year career. These days, there are more nods of agreement when he addresses a crowd, such as when he recently gave the JAR Distinguished Lecture in Anthropology in Albuquerque, N.M.

Smith said he is looking forward to a new edition of his book on the origin of modern humans that he originally wrote and published in 1984 with the late Frank Spencer. The new version is due out in 2013. Later this year, Smith will give the keynote address to a colloquium on later human evolution at the University of Tübingen in Germany. “I will certainly be pushing assimilation there,” he said.

Smith hopes the new DNA evidence will combat what he calls a prejudice against Neandertals. “I consider Neandertals people. As far as I’m concerned, if you met one today, you would be able to tell there was something different, but it’s not seeing a bipedal cow. These were people,” he said.

The drive to push stereotypes and demean Neandertals is part of an urge Smith calls “the other” factor. “It’s the idea that there is ‘us’ and there is ‘them,’” he said. “There is a need to ensure that ‘they’ are not perceived like us, and that we are better than they are.”

Smith made comparisons to the modern-day Europeans taking over land of the Native Americans. “Neandertals were the indigenous people in Europe. And when it comes to new populations coming into an area, the indigenous people always get the short end of the stick,” he said.

Neandertals were genetically made to survive cold weather, said Smith, and to spend more energy maintaining their own bodies than reproducing in large numbers. “Modern humans came in, wave after wave, for 4,000 years,” he said. “Demographically and genetically, Neandertals were just swamped. Modern humans were like a weed species. They just came in and took over everything.”

With the acceptance of the Assimilation Model, Smith hopes people can take away the additional idea of how all modern-day humans are alike. “For all these years, we have been seeming to focus on ‘racial’ difference – on black, white, brown, red, yellow,” said Smith. “When in reality, these are relatively minor, adaptive differences among recent groups of people. Modern humans are all mostly derived from the African variant of Homo sapiens. We are all fundamentally Africans.”

Africans, with a touch of Neandertal.