Editor’s note: This story was originally published in Illinois State alumni magazine in February 2002.

For Donald F. McHenry, the world is his office.

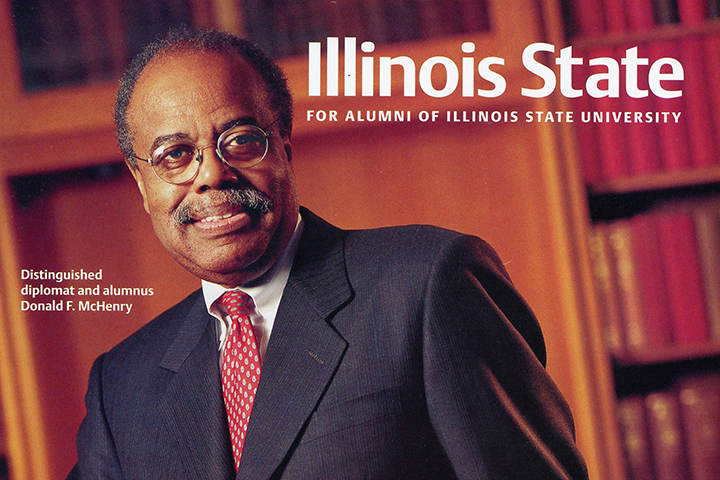

McHenry—a 1957 Illinois State University graduate, who received a Distinguished Alumnus Award in 1990—served as President Jimmy Carter’s top envoy to the United Nations during the explosive diplomatic era dominated by the Iranian hostage crisis and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Since then, McHenry has served as a diplomatic troubleshooter for the White House, State Department, and United Nations. These assignments have spanned making recommendations to the U.N. secretary-general about curbing violence in Algeria to being dispatched by President Bill Clinton on missions to Nigeria, a politically turbulent oil-rich African nation. In the aftermath of the 1998 bombings of two U.S. embassies in Africa—the suspected handiwork of terrorist Osama bin Laden—McHenry served on a commission that probed security and other issues related to U.S. embassy operations worldwide.

McHenry’s international portfolio also includes operating a “small boutique” consulting firm whose clients include multinational corporations, as well as membership on five corporate boards—including AT&T and Coca-Cola—whose interests span the international marketplace.

Donald F. McHenry, a 1957 Illinois State University graduate,

received a Distinguished Alumnus Award in 1990.

A distinguished professor in the practice of diplomacy and international affairs at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., McHenry also chairs a $370 million, 10-year Ford Foundation program aimed at extending graduate study opportunities to students from countries around the world with the exception of the United States and Europe.

This rich range of global activity explains in part why former Secretary of State Cyrus Vance in his memoirs described McHenry as “extraordinarily able” and a diplomat who exhibits “active and strong leadership.”

However, McHenry’s childhood in East St. Louis was a long way from the corridors of power in Washington and other foreign capitals.

“The East St. Louis that I grew up in,” McHenry recalled, “was relatively poor—but it’s worse now.”

McHenry credits his single mother’s strong influence for encouraging his educational pursuits.

“We didn’t play in the streets,” McHenry explained. “We went to the library and music events.”

At Illinois State, McHenry studied social science, which led him to politics. That interest was sparked by McHenry’s admiration for Adlai Stevenson, an Illinois governor and one-time Bloomington resident, who twice was the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate in the 1950s and served as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations from 1961 to 1965—a post McHenry held 14 years later. McHenry also was a champion collegiate debater, a skill that was a big asset for a future diplomat.

McHenry attended Illinois State at the dawn of the Civil Rights revolution just after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the desegregation of public schools. As a student, he helped launch and lead a local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the nation’s oldest civil rights group.

After graduating from Illinois State, McHenry earned a master’s degree in speech and political science from Southern Illinois University and pursued doctoral studies at Georgetown University.

He joined the State Department in 1963 and met Adlai Stevenson when he won a temporary assignment with the U.S. mission to the United Nations. Early in his diplomatic career McHenry dealt with colonial issues and by 1966 headed the office handling those matters.

However, as his career blossomed, he found himself taking on special assignments for Secretary of State Dean Rusk—assignments that took him to far-flung locales, including Colombia, Peru, and Iran.

When President Lyndon Johnson tapped William Rogers, President Eisenhower’s attorney general, for a three-month diplomatic troubleshooting mission involving the thorny issue of Southwest Africa, McHenry was part of Rogers’s team.

When President Richard Nixon appointed Rogers secretary of state, McHenry received a phone call asking him to join the transition team.

This led to a 1969-71 posting in the Office of the Counselor of the State Department, where McHenry was involved in National Security Council affairs.

But, as the United States became more deeply embroiled in the quagmire of Vietnam, McHenry said, things became increasingly “uncomfortable” for him. By day he diligently worked at the State Department. However, by “night” he opened his house to anti-Vietnam protesters from universities who needed a place to stay in Washington.

In 1971 McHenry went on leave without-pay from the State Department, joining the Brookings Institution and the Council on Foreign Relations, prestigious Washington, D.C.-based “think tanks,” and began teaching at Georgetown University. He was part of an exodus from the State Department by a group of young and talented diplomats who sharply disagreed with U.S. policy in Southeast Asia. Among McHenry’s disaffected colleagues were Richard Moose, who later served as undersecretary of state for management; Anthony Lake, national security advisor in the Clinton administration; and Richard Holbrooke, who was President Clinton’s U.N. ambassador.

Finally, in 1973, McHenry resigned from the State Department, taking a post at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. As the 1976 presidential campaign neared, Carnegie’s broad range of international experts—including McHenry—began providing foreign policy guidance to the Ford and Carter presidential campaigns.

“After the election,” McHenry said, “I was asked to work with the transition team dealing with staffing at the State Department and other foreign affairs agencies and to help get early policies in line.

“Many of us who had left the State Department and had scattered in different directions,” McHenry explained, “found our way to transition offices” after Jimmy Carter won the election.

So, McHenry again found himself working at the State Department, from November 1976 until January 1977, with every intention of returning to the Carnegie Endowment. But then his life changed.

Rep. Andrew Young, a Georgia Democrat, a former colleague of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was appointed United Nations ambassador by Carter. Vance wanted men of experience to be part of Young’s team of five ambassadors at the U.N. Consequently he lobbied for McHenry, who served as deputy U.S. representative to the U.N. Security Council from 1977 to 1979 and as U.S. permanent representative to the United Nations from 1979 to 1981.

“I had plenty of contact with President Carter,” McHenry said, citing several tough diplomatic wrangles in which he was a participant. These included the struggle for Namibian independence in Africa and a testy 72-hour Kennedy Airport standoff with the Soviets over the return to Moscow of Ludmila Vlasova, wife of Alexander Godunov, a Soviet ballet dancer who defected to the United States.

Despite his rigorous global schedule, McHenry has remained close to Illinois State University. He has pledged his personal papers, which chronicle his career, to Milner Library—a tremendous boon to future researchers.

McHenry also serves as honorary co-chairperson of Redefining “normal,” The Campaign for Illinois State University. He will host a wide-ranging discussion of global issues in March as part of the campaign kickoff festivities.

“It is clear that a modern university needs resources,” McHenry explained, referring to the importance of the comprehensive fund-raising effort. “A state university can’t run simply on the resources provided by the state. The funds provided by the campaign will allow an emphasis on new projects—projects that will be attractive to faculty and to high-caliber students.”

When Donald McHenry recalls his days at Illinois State University, he simply smiles and says, “It was a good place to be.”

Lessons learned

Donald F. McHenry learned many lessons from two of his foreign policy heroes.

Joseph Sisco was a brusque career diplomat who capped his distinguished career as undersecretary of state. Early in his career, McHenry heard Sisco grumble an adage that stuck with him: “Don’t tell me something can’t be done. You just haven’t found the way.”

McHenry fondly added: “I learned a hell of a lot from him.”

Harlan Cleveland served as assistant secretary of state under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. From Cleveland, McHenry learned the importance of teamwork.

Cleveland, according to McHenry, was an “idea man,” a visionary. He knew he wasn’t good at infighting, a staple of the Washington landscape. So, he felt comfortable working with someone like Sisco, who, according to McHenry, was “combative” and “hated to lose.”

“Cleveland taught me,” McHenry said, “that you don’t need all the strengths in one person. You might need two or three people to complement each other. People should be big enough to be comfortable with that.”

Paying the price

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks on the United States and the military campaign to root out and destroy Osama bin Laden’s terror network harbored in Afghanistan, Donald F. McHenry sees telltale signs of the Cold War.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan took place on McHenry’s watch as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Now, Afghanistan again is an international battleground.

“We’re paying the price for some past policies,” McHenry opined, “policies we saw simply through a Cold War lens.

“There was an error at the end of the Cold War,” McHenry added. “We dropped Afghanistan like a hot potato. There was a vacuum after the Soviet defeat.”

The Soviets saw a threat in Afghanistan—religious fundamentalism—that could infect the Moslem peoples of the old Soviet Central Asian republics. Now those same extremists are sheltering bin Laden, the assumed godfather of an international terror network that toppled the World Trade Center and left a gaping hole in the Pentagon, killing thousands on the ground and others aboard three airliners turned into missiles.

McHenry believes a U.S. policy of multilateralism—coalition building—will be a key ingredient to successfully coping with the terrorist threat.

“The U.S. can’t survive by itself,” he explained.

McHenry’s long and varied diplomatic experience also cautions that terrorism may be reduced—but not eliminated—and that to do so the U.S. will have to moderate its language in the interests of coalition building, while recognizing that it’s facing a long and difficult process that will take much more than military action to be successful.