There was a time when money literally grew on trees. It might seem like a dream, and a sweet one at that, but Illinois State’s Assistant Professor of Anthropology Kathryn Sampeck has unearthed a time when people used cacao beans – the basis of chocolate – as currency.

While on sites several years back in what is now western El Salvador, she became intrigued with a group known as the Pipil, who thrived in the 1400s. “The Pipil had the same culture as the Aztecs and the same dynastic state organization, but this area had a vast production of cacao beans,” said Sampeck. While translating early documents from the area, known as the Izalcos, she found an annual export of 1.2 billion cacao beans coming out of one port alone.

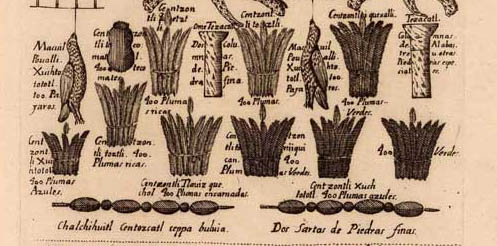

The Pipil went beyond a simple talent for exports. With the proliferation of the coveted beans, the Pipil used an intricate system of currency, with cacao as the small denominations. “Think of it as pocket change,” said Sampeck. “It was part of a shift to a monetized economy, one of the first in Mesoamerica. These were the first people to rely on money in a major way. We don’t even see this with the Aztecs.”

The Pipil’s monetary system thrived in the late 1400s and early 1500s, just before the Spanish Conquistadors overran the area. “People like to attribute the introduction of a money system to the Spanish, but in essence, the Pipil were the first bankers of the Pre-Columbian era,” said Sampeck.

Curious to know more, Sampeck followed the money – or the documents on money – to a fellowship with the John Carter Library at Brown University where she could study rare colonial manuscripts and books. “There are entries that explain what a cacao might buy,” she said, noting someone with ten cacao beans could purchase a hen. Of course, the cacao was one of the lowest forms of payment. “To get the big ticket items, you needed to pay in bolts of cotton cloth or copper axes,” she added.

What made cacao beans unique is that they never stopped being consumed during their transition to currency. “There is evidence of people drinking cacao as early as 4,000 B.C.E. with cacao residue found in vessels,” said Sampeck. As the beans evolved to a form of currency, the cacao drink – the main way people consumed the bean – became more exclusive. “You might think of it the way they make those $10,000 cupcakes inlaid with real gold today,” said Sampeck. “It happens, but it’s obviously not for everyone.”

The arrival of the Spanish in the early 1500s helped propel cacao beans as currency due to a currency crisis in Europe at the time. “There were no government-run mints in Europe, so those that did mint money usually minted large denominations. That’s great, but how do you give change if you only have the equivalent of a $100 bill?” said Sampeck. She noted the Spanish in the Izalcos region quickly adopted the Pipil’s cacao-bean currency, and helped push the cacao to Europe, where it was slowly catching on as a drink for the upper classes. By the late 1600s, shops that served cacao drinks appeared in different parts of Europe.

Through her research, Sampeck is now following how cacao was used as a commodity through Europe and the American colonies. “Cacao was not a huge portion of the colonial market, especially not compared to rum and sugar,” she said. ““But those who did trade in it could have clients who were miles away. This spread out network shows how chocolate helped unite colonists through their tastes. Cacao created bridges within and between colonies.”

Of course, these days, Americans spend around $13 billion a year on chocolate. It is a far cry from the Pipil’s pocket change, and perhaps a debt all chocolate lovers owe them.