Have you ever had a question even the Internet couldn’t answer? Some members of the Illinois State University community did. And we put Illinois State University’s faculty experts to work answering their inquiries.

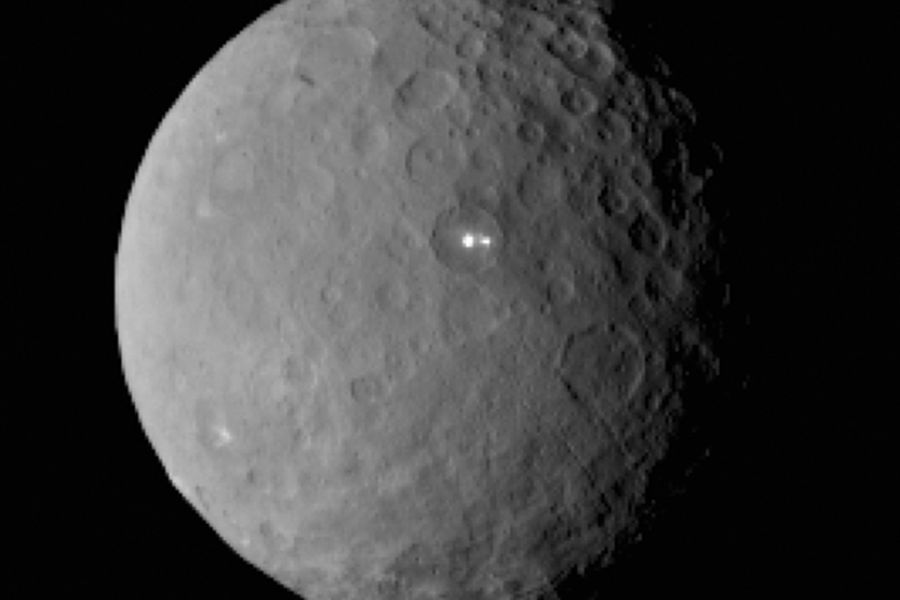

What are those two shining lights on planet Ceres?

—Mark Wesolowski ’91, Chicago

Astronomers, like all scientists, are explorers. Visiting new worlds guarantees unexpected mysteries, with each new discovery initially challenging to explain. The two bright spots, in a crater on the dwarf planet Ceres, are the latest example. Finding and solving such mysteries is one of the reasons we explore the far reaches of our solar system.

The bright spots on Ceres are sunlight reflected from the edge of an impact crater. Yet what reflects this light? Is it piled ice or salt, recently churned up from beneath the surface of Ceres by a meteor impact? Or is the ice reflected by something else? Only further exploration of Ceres will tell.

We see a similar phenomenon on Umbriel. This is one of the heavily cratered moons of Uranus. There, irregular patches of sunlight shine from the Wunda Crater. Perhaps the bright spots on Ceres will help us better understand what is also happening on Umbriel.

I hope that the Dawn space probe reveals the source of these lights as the probe gets a closer look at Ceres. We might discover that water, in the form of buried ice, is common throughout our Solar System. Then again … maybe not. Solving mysteries like this is why we explore the many and varied worlds that orbit our sun.

Tom Willmitch, director, Illinois State University Planetarium

Why can’t I tickle myself? I’m one of the most ticklish people I know! My friends (and wife) can’t tickle themselves either. How come?

—J Thomas (Tom) Stoltz ’90, Bangkok, Thailand

What you think you are seeing or feeling is not the real world. It is being preprocessed by your nervous system.

Your nervous system does not work like a storage device. It is not a camera, taking in everything around you. Your brain only pays attention to important things—when something is novel or new. Anything that is familiar, your brain sees as useless or unnecessary information.

When you are performing an action, your brain sends signals to your muscles, and the muscles move. But that is not all—a copy of that signal, called an “efference copy,” is kept and subtracted from signals of your sensory system. If your actions happen as expected, the efference copy matches the sensory information and no sensory information reaches the brain.

I touch the computer mouse, and it is only the computer mouse. But say you reach down for your computer mouse, and there is a spider on it. That is very different than what you expect. You feel that spider. Your “efference copy” does not match; your brain realizes the difference and pulls your hand back.

When we try to tickle ourselves, we have an expectation of what will happen. The expectation is met. That means the efference copy matches, so the tickling sensation does not reach the brain. No reaction.

On the flip side, the expectation has to come from our own nervous system for the brain to have a chance to ignore it. If we see someone coming to tickle us, we will still laugh because it was not our brain that sent the signal, so there is no efference copy, and the message reaches the brain. You laugh.

Wolfgang Stein, associate professor of neuroscience, School of Biological Sciences

This woodblock print, titled “A Plum,” is by the 20th-century Japanese printmaker Junichiro Skein (1914–1988).

My fiance (Dan Jones ’07) and I were recently doing a spring cleaning of our basement and found a piece of art that belonged to his grandfather. I’ve tried to do some research on the artist but don’t really know where to start. Any information on the background of this piece would be much appreciated!

—Kristen Massey ’06, St. Louis

This woodblock print is by the 20th-century Japanese printmaker Junichiro Skein (1914–1988). It is titled A Plum. I found it on artnet.com under auctions. You could find the exact price this print sold for if you pay for a (one-day pass) to the auction database. His auction prices for woodblocks range from a few hundred dollars to a few thousand.

All I did was guess the lettering of the signature until I found a likely match. I knew it was Japanese because of the insignia.

Barry Blinderman, director, University Galleries

Who invented soft soap and why?

—John Klein (father of Alec Klein ’15), Vernon Hills

(Editorial note: Ah John, we love the John Cusack movie The Sure Thing as well, and that is arguably one of the best quotes in the movie. Perhaps we’ll never really know why liquid soap was invented, but we can talk about why liquid soap looks the way it does.)

The origins of soap as a cleaning agent can be traced back to the ancient world (~600 B.C., Greek city states). However, liquid soaps were not commercially available until the late 19th century. The most well-known liquid soap at this time was Palmolive soap (from palm and olive oils) developed by a researcher named B.J. Johnson.

As the chemistry of soaps has become more evolved, liquid soaps may contain chemical compounds known as saponified vegetable oils. It is also possible that they may contain chemical agents like sodium laury sulfate as an emulsifying detergent to dissolve oil and dirt for cleaning. There are numerous other ingredients, such as oils, anti-bacterial agents like triclosan, fragrances, and colors—both natural and synthetic—to suit the interest of the consumer.

When all combined these chemical agents create liquid soap, the material has an oil consistency, primarily due to the properties of the emulsifying detergent that’s being used as the key ingredient.

Shawn Hitchcock, professor of organic chemistry, Department of Chemistry

What effect do you think branding had on the last presidential election, and do you think it will have an impact on the next?

—Tina Krumdick ’85, Lisle

We used to understand branding as a one-way activity engaged in by the communicator in question, whether a person or organization. The more traditional ways of responding to political attacks (via press conference, or occasionally, defensive advertising) have trouble repairing this damage because of lack of access to their opponent’s best resource: the social network feed.

Social media has changed branding, especially in contested campaigns where each party’s objective is to make their opponents seem less preferable. The candidate with the better social media network and message designs can define his/her opponent’s public image in ever more efficient ways.

A good example of this is Republican nominee Mitt Romney’s statement that as governor of Massachusetts he sought and obtained “binders full of women” in order to improve hiring of women in his administration. He said this in order to compare his efforts favorably with what President Barack Obama had not achieved in terms of gender equity. This small phrase became a widespread social media meme taken to show Romney as viewing women as some sort of objective commodity, which was precisely the exact opposite of Romney’s intent.

Incidents such as this provide evidence that social media have the potential to increase the number of people exposed to political content and potentially galvanized for causes and candidates. It also raises concerns that it may not help improve our level of political discourse and civility.

Joseph Blaney, professor of communication and associate dean, School of Communication and College of Arts and Sciences

What is the probability of a Chicago Cubs World Series Championship in 2015?

—Brian Bernardoni ’91, Justice

There are multiple methods to calculate a probability. A classical approach is equally likely outcomes. There are 30 teams in Major League Baseball, and if each has the same chance of winning the World Series, the probability is one divided by 30. This calculation results in .033 or a 3.3 percent chance.

Somewhat related to this approach is relative frequency. Since the Cubs have not won the World Series since 1908, the relative frequency is less than 1 out of 100. At a much more technical level the often misapplied law of averages is better interpreted as each year begins anew. Still less than 1 percent.

As of early morning May 25, the Cubs had the ninth best record in baseball, 3.5 games behind the Cardinals. Sorry—my bias is emerging! Based on this record and a sophisticated analysis/prognosis, the consensus of the Sports Book in Las Vegas is a 7.7 percent chance. Follow the money for the most realistic estimate.

Robert Shoop, instructional assistant professor, Department of Management and Quantitative Methods

To submit a question for one of Illinois State’s experts, email Kevin Bersett or tweet the question to @ISUResearch. Please provide your name, affiliation with the University if applicable, and town of residence.