Holocaust Remembrance Day begins the evening of May 4. Amid those attending the ceremonies and remembrances to honor the millions slaughtered in the Holocaust will be those who carry the burden of memories they never experienced—the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of those who survived.

Illinois State University faculty look at Holocaust survivors’ guilt as it is passed from generation to generation, and comment on the idea that no one could see the Holocaust coming.

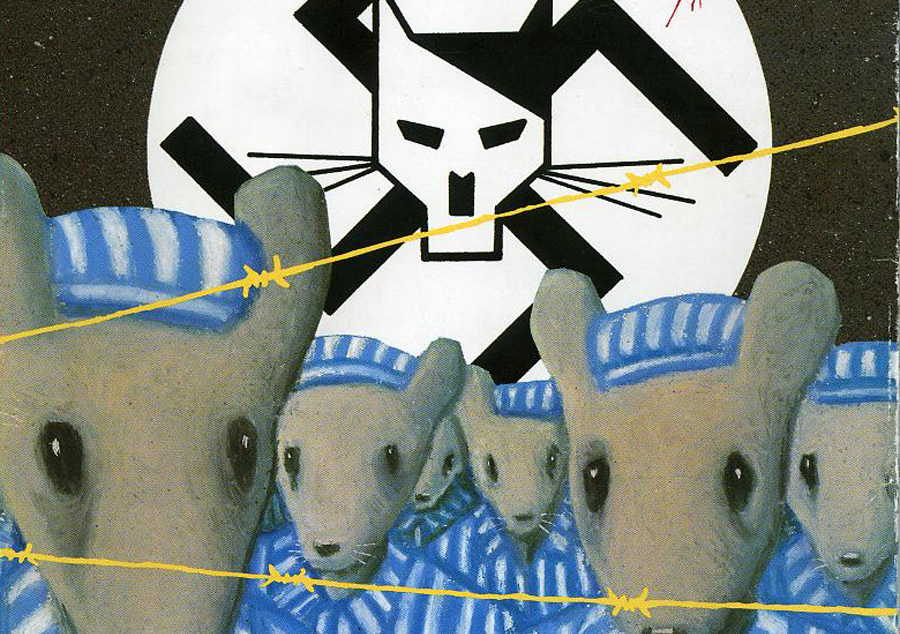

The concept of Holocaust survivors’ guilt was immortalized in the graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman, which just celebrated its 35th anniversary. “Maus is the story of Spiegelman’s parents, really his father Vladek’s story,” said Professor of English Jan Susina. “It is a powerful story about the Holocaust, but it is also a powerful story about parents and children.”

In the novel, Spiegelman lets Vladek tell his story through flashbacks. His father takes the reader to Poland where Jews—including him and his wife Anna—were rounded up and forced into ghettos where they nearly starved, before being sent to Auschwitz. At that death camp, they faced starvation and the gas chambers, while watching others being worked to death.

The heroic tale of survival that Vladek weaves starkly contrasts the frail, weak father Spiegelman knows, who refuses to mourn his wife’s suicide, obsessively hoards money, and counts pills in fear of another Holocaust. “On top of growing up with this broken man, Spiegelman feels he can never measure up. He says in Maus, ‘Nothing I do will ever compare to surviving Auschwitz,’” said Susina.

Professor of Psychology Raymond Bergner said survivors’ guilt is peculiar in that it is “guilt without perceived wrongdoing.” While most guilt can manifest itself in different ways throughout life, Bergner noted survivors’ guilt carries a burden of its own. “Survivors don’t feel guilty because they did something wrong. They feel guilty because they lived,” he said. Bergner noted the guilt is compounded when parents lose a child, or see children die. “They believe they have lived their fair share of life when children died before they had a chance to live.”

It is only in hindsight we see writing on the wall. For the Jews living in that time, there was no writing, and there was no wall. — Katrin Paehler

The guilt of surviving can be passed on for generations, said Bergner, who mentioned a former Illinois State student. “His parents survived the Holocaust and came to Chicago,” said Bergner. “His father told his three children, ‘If even one of you gets a college education, then all our suffering will have been redeemed.’” After the student’s older siblings declined to go to college, he was the only one left to fulfill his father’s dream. “So he came to ISU, even though college just wasn’t for him. There was this terrible, terrible burden to redeem his parents’ suffering.”

Bergner, who mentions survivors’ guilt in his lecture on post-traumatic stress disorder for veterans, said extreme trauma—whether on the battlefield or in a death camp—can shake the foundations of a person’s beliefs. “People believe in a just world, where everyone gets what they deserve,” said Bergner. “When they survive and others die—and they believe they are no more deserving than the others—they’ve gotten something they don’t deserve. And that is something they feel guilty about.”

For many survivors, it was older and younger relatives who perished in the death camps and at the hands of the mobile killing squads of the Nazis. “Students always ask why people didn’t resist or leave,” said Professor of History Katrin Paehler, who teaches the history of the Holocaust. “I talk about family connections, and that resistance is a young man’s and woman’s game.”

Paehler often tells students of Jewish resistance fighter Abba Kovner, a youth leader in the Jewish ghetto of Vilna in the Soviet Union. Kovner took resistance fighters from the ghetto and they actually survived in the forest. “Kovner once said that as he was taking young fighters out of the ghetto, his mother asked him what to do. He left her in the ghetto,” said Paehler. “You can’t take an old woman into the forest and expect her to survive. Yet ever since then, he asked himself, ‘Am I a hero or a bad son?’”

Holocaust survivor guilt can be compounded by the idea that Jews and other targeted groups should have left Europe before they were rounded up. Paehler dismisses this idea as “the gift of hindsight.”

“It made no sense what was happening. In Germany, it was a very slow process. It is only in hindsight we see writing on the wall. For the Jews living in that time, there was no writing, and there was no wall,” said Paehler, who added that before places like Auschwitz and the killing fields in the Soviet Union, the only frame of reference for Jews were the pogroms, or series of violent, anti-Semitic murders. “They thought perhaps another pogrom was coming, but not Auschwitz. Nobody saw that coming. So looking at it from today’s perspective completely skews our thinking.”

For years, Spiegelman sought to gain an understanding of his father, if not redeem him. He continued to work on his iconic Maus—including a CD of his interviews with his father in the expanded work MetaMaus, helping create a traveling museum exhibit, and working on a play. “Maus is this stunning achievement of Spiegelman, but one he can ultimately never escape,” said Susina, who added Spiegelman has always worked to keep Vladek’s memories from falling into legend. “When Maus came out, it was a bestseller. And Spiegelman took the New York Times to task because they had it on the fiction list. He said, ‘This isn’t fiction. This is my father’s life, my life.’”

There is a scene in a comic memoir reprinted in Breakdowns where Spiegelman hands his son, Dash, a present. When the boy opens it, it is a monster emblazoned with a swastika. This “gift” is the curse of the Holocaust, which Vladek gave to Spiegelman, and will someday be carried by his son.