Kathryn Jasper and Lea Cline have never seen a student weep when looking at a picture of the Colosseum in Rome.

Yet the two, who developed a study abroad curriculum that interweaves their disciplines, have witnessed many a teary eye when they stand with students in front of the actual Colosseum. “When you see a student crying with joy, you know you have made an impact,” said Jasper.

“Of course, we’re nerds about this stuff, so we tend to get teary as well,” added Cline.

Both assistant professors at Illinois State, Cline teaches courses on ancient art history in the School of Art, and Jasper teaches ancient and medieval history in the Department of History. They are planning their third study abroad trip for summer 2017, teaching ancient art and medieval history in Italy.

It’s all part of an ongoing, interdisciplinary collaboration between Cline and Jasper, geared toward making studying art history and history more seamless for students.

Each arriving at Illinois State in 2012, both realized quickly that students who wanted to take courses in both history and art history faced an uphill battle. Art history courses jumped from 100-level introductory courses to 300-level courses in the School of Art, leaving interested non-majors with limited chances to explore their interests. “History students were trying to come into 300-level art history classes without any real background in what the study of art history really entails,” said Cline. “The discipline-specific vocabulary and research process was confusing, meaning that history students were feeling lost before they even started.”

It is no longer acceptable to teach historical art as though it existed in a cultural vacuum. —Lea Cline

In an effort to ease the transition, Cline worked with her art history colleagues to develop a new curriculum that includes 200-level art history courses, and lowered the number of requirements for the classes. “If you are a Spanish literature major, and just really want to take an art history class, now you can, as long as you have gotten past the initial general education courses,” said Cline. At the same time, she and Jasper began working on upper-level courses that could combine their disciplines.

“As any academic knows, disciplines are arbitrary,” said Jasper. “So if you are studying Rome, why wouldn’t you look at the art and architecture? We historians sometimes use pictures of art as backdrops, rather than actually discussing them as art of the time period. And the students lose so much when that happens.”

Cline nodded in agreement. “It’s just like art historians who are guilty of propping up a major historical figure as if he or she is a side note to the art,” said Cline. “But the idea of siloed disciplines has shifted. It is no longer acceptable to teach historical art as though it existed in a cultural vacuum. My collaboration with Katie is an outward sign of the more integrated approach to teaching history and culture that we both learned in graduate school.”

Cline and Jasper each developed a 300-level seminar in their field. And they work to teach the classes at the same time, allowing them to combine classes from time to time. “We work very closely, so that I’m contextualizing the things she is doing, and vice versa,” said Jasper, who added she notices when a student is sparked by something Cline said in her class. “I try to proactively send my students to Lea, because we both want that holistic approach to studying the ancient and medieval periods.”

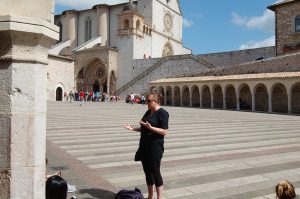

Three years ago, Cline and Jasper extended their collaboration to a joint study abroad to Italy with the Orvieto summer program. Along with work in a classroom in their “home” location in Orvieto (a 15th-century palazzo), students take day trips to Assisi and Siena, and overnight trips to Rome and Florence. “In Assisi, Katie gives an amazing, day-long introduction to St. Francis. She provides context in the form of a discussion about Italian monasticism in the 13th and 14th centuries, religious life in the medieval period, period politics, and how a man like Francis would have come to interact with the Pope,” said Cline. “I learn something new every time we go to Assisi.”

Jasper pointed to Cline and added, “And Lea does the same thing when we go to Rome and walk the Colosseum or the Forum.”

With each trip, the curriculum evolves. “When we first started, my narrative was divorced from Lea’s,” said Jasper. “We were covering similar material, but not sharing lesson plans. So her students were focusing on different things than mine. Now we’ll be concentrating on the same areas.”

Cline noted students will still be enrolled in either an art history class or a history class, but the collaborative curriculum will improve the course flow. “I used to teach about the art of the area, and then Katie would talk about the history,” said Cline. “Now it will be more cohesive, but it won’t feel like a departure. We’ll teach together, and develop richer conversations with students as we visit these important historical sites.”

The study abroad courses are also being converted to 200-level classes that can count for credit in the general education sequence, rather than as an elective, meaning that all students will earn credit toward their degrees (no matter the major) while abroad. Cline’s course is already listed as ART 282 Art History Abroad, and Jasper is working to create a similar 200-level for the Department of History.

Cline and Jasper, who both studied in Italy in their graduate days under the Fulbright Program, agreed how much they love watching students grow during their travels. “This is a class in three dimensions,” said Cline. “I see every minute as a chance for students to learn. And, when you see a student ‘get it’ for the first time—really ‘get it’— it can bring you to tears.”