I get the feeling that Mennonite College of Nursing Associate Professor Wendy Woith brings a personal touch everywhere she goes. When I walk into her office, my gaze lands on trinkets from her adventures in Russia, newspaper clippings, photo booth pictures of her late parents. Her Ph.D. dissertation sits proudly on the shelves next to well-read books and a cozy mug. I might be there for an interview, but I’d just as easily stop by for tea.

On curiosity, travel, and a love for research

Whether we’re undergraduate students or working on our graduate degree, the word “research” can sound cold and daunting. Mention research to Woith, on the other hand, and it’s like flipping on a light switch.

“I love talking to students about it,” she says. “Research is such a valuable skill—one they can use in their workplace, wherever they end up. And it’s fun, too!”

This semester, she is teaching Research Theory for Evidence-Based Practice, a course designed to prepare new nurses for a future role as experts in improving patient care. In her graduate Qualitative Research course, doctoral students learn about the various qualitative research methods.

Her love for research is contagious, and for her, it’s a perfect fit.

“I’m really curious and ask a lot of questions. I’ve been that way all my life,” she says. “With research, you take things you want to learn more about, and you just dive in.”

“I’m really curious and ask a lot of questions. I’ve been that way all my life.”—Wendy Woith

That’s just what she did when she was a graduate student, too. We sit down at a small table in her office, and she shares the story of her own research journey. In 1999, she met Dr. Grigory Volchenkov—a cardiologist who is now the chief physician of the Vladimir Tuberculosis Control Programme—while she was providing staff development programs to Russian nurses at the cardiac hospital.

“Grigory is someone who just wants to make the world a better place,” Woith says.

It’s clear that she does as well. She returned to Vladimir in the fall of 1999 and again in 2001 to present at medical conferences. Her work with the Russian health care system inspired her dissertation on tuberculosis in Russia, which has led to recurring research visits throughout her career.

“I did most of my work in Normal’s sister city: Vladimir,” Woith tells me. There, she investigated whether social stigma and different degrees of understanding about tuberculosis could predict whether or not a patient sought and adhered to treatment.

Later, in a return visit, she studied how well health care workers in Russia understood infection control measures in tuberculosis treatment. “We found that, although doctors had the most knowledge of TB infection control measures, overall knowledge scores were low.” These findings are significant because they have led to a revision of staff education programs.

There was another problem as well: health care workers were at a much higher risk of developing tuberculosis from treating patients. Woith tells me that health care workers must wear respirators when providing care to patients with active TB. In the tuberculosis hospitals of Russia, nurses were working eight- to 24-hour shifts on units where there were no negative pressure isolation rooms. “It’s uncomfortable to wear a respirator for those extended periods of time,” Woith explains. “Often, they would just keep the respirator off.”

On creativity in research practices

So what makes patients follow treatment plans? And what makes nurses wear personal protective equipment despite discomfort?

According to Woith, “Most likely, it’s the desire to protect the ones you love.”

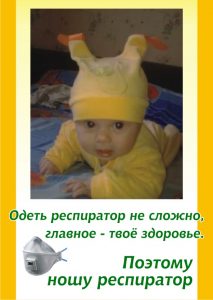

An example of PhotoVoice. Translation: “It’s not hard to put on a respirator; the main thing is your health.”

Woith and her colleagues conducted a study using PhotoVoice, a qualitative research technique that involves subjects taking photos that represent their own lives, then telling a story about the photo.

“Health care workers at the hospital took photos of someone they loved and hung them around the hospital as a reminder: I want to stay healthy to keep my loved one healthy,” she says.

The result? More workers put on the bulky respirators. These photos told stories that created real change in that hospital community, making it a powerful research tool for other settings as well—maybe even the classroom. But that’s a story for another time.

Back in Normal with her students, Woith emphasizes that one of the many benefits of working with nurses in other cultures is that it provides opportunities to exchange ideas. “There is no one way that is better. There are different ways of looking at the world. How do we share our ideas in order to improve our practices?”

She also highlights the role research has in facilitating the critical thinking and creativity that are necessary to improving nursing practice. For example, she is preparing a study using geospatial technology to map where tuberculosis is within the Vladimir region of Russia. This will help health care workers understand how and where the disease is spreading and decide what changes to implement.

On advocacy and research methods

Woith’s work in Russia has had a huge impact on her teaching. “While there, I learned that teaching, service, and research go hand-in-hand.”

She shares this with her students, too. Her Research Theory for Evidence-Based Practice course this fall was designed to prepare new nurses for the role they are expected to play in improving patient care. Students learn how to search for and evaluate sources, how to interpret data, and how to use evidence to make changes. But what she most wants to instill in her students is a passion for advocacy.

“Be an advocate for everybody,” she says with a smile.

How do you get students excited about advocacy and research methods? “You tell stories.” Stories like the ones she has shared with me for this article: about real people, real problems, and creative solutions.

Bryanna Tidmarsh is a PhD student in English Studies at Illinois State University.