School suspensions are counterintuitive in nature, says Charles Bell, who uses his own experiences growing up in Detroit to help others tap into their potential.

School suspensions are intended to remove “trouble” students from the educational environment—temporarily defusing problems. In financially strapped districts, however, suspensions are being used as a first resort to relieve overcrowded classrooms, said school discipline researcher Charles Bell. The result is extended suspensions over sometimes minor infractions, and placing more students on a downward spiral that includes academic failure, school dropout, and incarceration.

“Suspensions are counterintuitive in nature. We want students to learn, and yet we are taking them out of an environment that has the resources and pro-social benefits to help them,” said Bell. An assistant professor of criminal justice at Illinois State, Bell has spent several years studying African American students’ and parents’ perceptions of school discipline.

You lose a friend who is killed at 14. You watch a friend who is 16 get arrested, and the idea of making it to 20 seems unrealistic. Most people are thinking, ‘I have to survive today.’ — Charles Bell

Joining the faculty of Illinois State in 2018, Bell gathered the study’s data while completing his doctorate at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan. “Despite school discipline reform laws passed in 2016, in the 2017-18 school year Detroit Public Schools issued approximately 16,000 school suspensions. The district only has about 48,000 students so they issued on average one suspension for every three students,” said Bell, who noted students in his study drew suspensions for something as simple as a dress code violation, which is even more striking in impoverished areas where students often cannot afford updated uniforms.

Over the last 20 years, poor educational funding in Michigan has led to the closure of 160 schools in the Detroit area, which compounds overcrowding. “When you have 40 students in a classroom, are underfunded and understaffed, you use what you have at your disposal to eliminate a problem. You don’t have time for one-on-one meetings with the students,” said Bell, who has presented his research for the American Society of Criminology, the American Sociological Association, and the Society for the Student of Social Problems in Quebec.

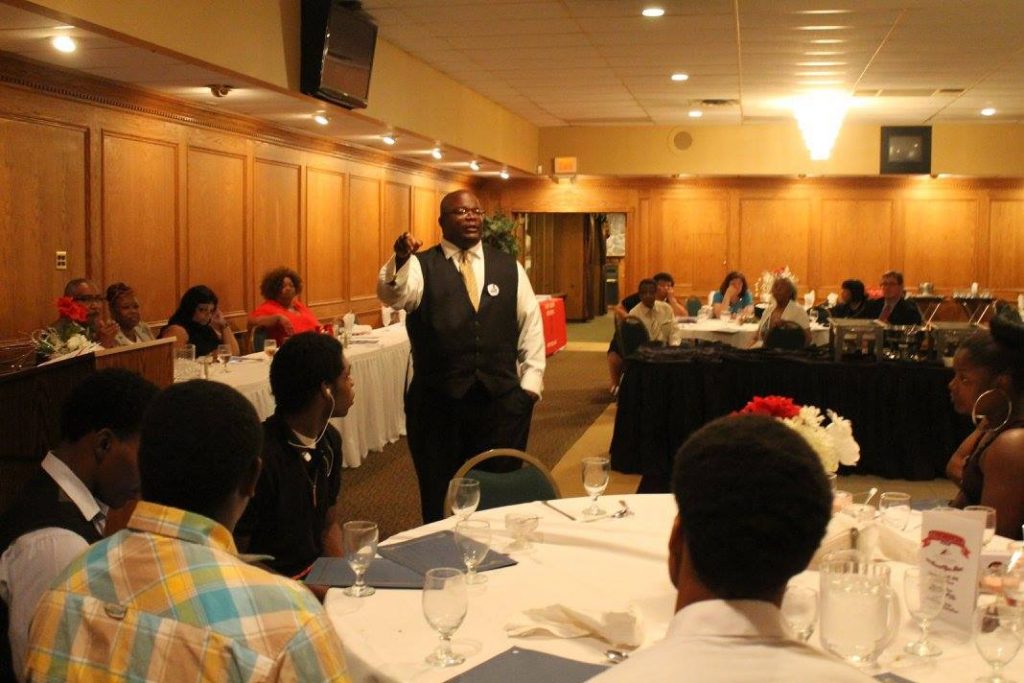

Charles Bell, Ph.D., speaking to high school students in the Detroit community about the importance of higher education.

In the study, students who returned from a suspension often said they found it difficult to catch up on work, or even overcome the negative perception that they did not want to be there. “In many cases, students felt they were just written off by teachers who were seen as resistant to letting suspended students make up work,” he said. “It begins a spiral of falling behind academically.” This leads to what Bell calls “black educational flight,” or parents taking students out of poorly funded predominantly African American schools, and placing them in schools with predominantly white children. “Parents are viewing white high schools as less punitive in nature,” he said.

That flight concerns Bell, who grew up in the north end of Detroit. Though only a few miles from Wayne State, he said the university seemed like a world away. “Really, the only way I watched people leave my neighborhood was in handcuffs,” said Bell, who noted most young people are looking to survive. “You lose a friend who is killed at 14. You watch a friend who is 16 get arrested, and the idea of making it to 20 seems unrealistic,” said Bell. “Most people are thinking, ‘I have to survive today.’”

When they pronounced me as Dr. Bell, so many people now saw something they thought was impossible. I want students to see what is possible.— Charles Bell

When his own high school counselor told Bell he qualified for a college scholarship, Bell said he looked at him in disbelief. “I didn’t know anyone in my community who had graduated from college,” he said, adding that Detroit has one of the lowest percentages of adults who hold bachelor’s degrees—13 percent. As he advanced at Wayne State and Michigan State, Bell said he recognized the look of doubt on the faces of young African American students coming behind him. “These students have all the potential in the world—good test scores, good grades—but they just don’t believe it is possible. We’re looking at the failure of public education to meet the needs of urban, impoverished students.”

That imbalance tips the scales against the future of African American students. According to the Pew Research Center, African-Americans make up 12 percent of the total U.S. adult population but account for 33 percent of the share of people in prison.

Along with his studies, Bell is working on the national Initiative for Maximizing Student Development. “I know that with each step I took, my neighborhood was watching,” he said. “My community came to my dissertation defense. When they pronounced me as Dr. Bell, so many people now saw something they thought was impossible. I want students to see what is possible.”

The research studies Bell conducts are geared toward helping educators understand the negative perceptions of a school removal-first approach, but he also advocates for students and parents to play a more active role in the disciplinary process. “Allowing students to have a voice, and hearing what parents have to say, is so important to establishing a cohesive education environment in which students can benefit, learn, and grow into the scholars that we want them to be,” Bell said.

Bell said his next study will include a comparison of students’ and parents’ perceptions of school discipline in Michigan and Illinois high schools.