Recruitment efforts led by Illinois State’s Office of Admissions are focused on increasing enrollment and retention of underrepresented students in programs across campus. In 2018, the University raised enrollment of African American students by 7 percent, with Hispanic and Latino students up by more than 5 percent.

In the field of education, much work is left to be done. In Illinois and across the U.S., approximately 50 percent of school-aged students are from underrepresented groups, compared to 20 percent of their teachers.

Kelli Appel, the College of Education’s director of enrollment and transition services, said the college works in close collaboration with community colleges across the state to engage prospective Illinois State education majors—particularly those from underrepresented groups.

“We also engage our K–12 school partners to help create teacher clubs and organize trips to campus with diverse districts, including Peoria, Decatur, and Chicago Public Schools,” she said. The college’s National Center for Urban Education (NCUE) similarly helps teachers in urban areas set up TEACH clubs and fund trips to campus for aspiring educators.

“We work with Admissions to focus primarily on neighborhood schools that do not get much attention from college recruiters at other universities,” said Maria Zamudio, NCUE executive director.

A normal landing spot

Diverse, talented, aspiring teachers choose Illinois State. The University continuously enrolls twice as many Golden Apple Scholars as any other university in the state. The nonprofit recruits and supports high-achieving, diverse future teachers.

Scholars receive rigorous professional support and a four-year scholarship to any one of 52 eligible teacher preparation institutions across the state. In exchange, they commit to serving high-needs Illinois schools for at least five years following graduation.

The importance of a diverse teacher workforce cannot be overstated.

“Longitudinal data demonstrate if a black student has just one black teacher in elementary school, the dropout rate reduces by almost 30 percent,” said Associate Professor April Mustian. She leads an urban-focused sequence called INFUSE in the Department of Special Education. “These students are significantly more likely to enroll in college, too. That’s profound.”

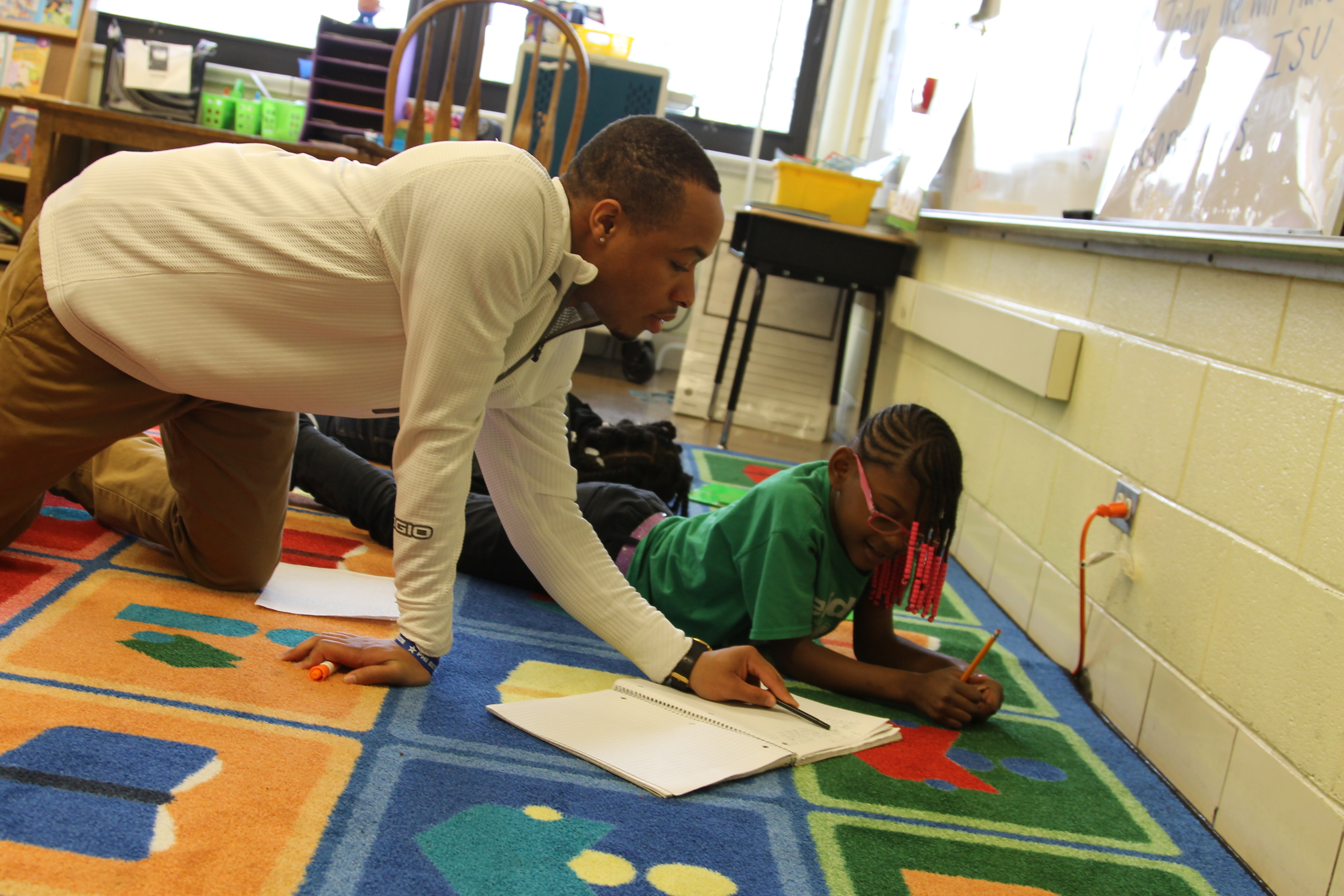

Redbird alumnus and Golden Apple Scholar Daniel Jackson ’18 is focused on being a teacher who makes a positive impact. After graduation, he returned to Chicago to teach second grade at Dixon Elementary School.

During his time at Illinois State, he was also a Bowman Fellow. The program was established by an anonymous donor in recognition of former Illinois State University President Al Bowman, to support underrepresented education majors like Jackson. The program provides Fellows with scholarship funding, mentoring, and professional development.

“A big part of the program was sharing my experiences with the people in the group because they looked like me, and they were going through similar issues that I was going through,” he said.

Jackson tabs the Bowman Fellows’ faculty advisor, Associate Professor Pam Hoff, as among those who had the largest impact on his development as a teacher and a community member. He said he frequently made use of her open-door policy.

Hoff embraces every opportunity to provide underrepresented students with a safe spot to share their experiences, whether they are related to jarring developments reported in the media or in their personal lives.

“I think what I have been proudest of is providing refuge and advocating for many students of color, particularly in teacher education,” she said.

Assistant Professor Becky Beucher believes the value of teachers who share one or more identities becomes particularly important during instances of marginalization.

“Because I identify as queer and as a cisgendered female, there is a visceral feeling, a pain I can feel when others who share my identity hear a homophobic comment,” she said. “That connection with a student is powerful.”

This is one of the reasons why she believes teachers who possess multiple minority identities are particularly important when connecting to a range of oppressed groups. “If we are fighting at the margins of the margins, everyone is going to benefit,” Beucher said.

“That level of oppression will impact anyone else who experiences a threat. So, if you are talking about the ways in which transgender females of color are oppressed, that’s going to benefit people of color, the LGBTQ community, women and in turn, it is also going to benefit cisgender men.”

Prepared to help all students

In addition to diversifying the teacher workforce, many are quick to point out an equal need to prepare educators who can set up equitable classroom environments, regardless of their backgrounds.

Jackson said that he and the other Bowman Fellows felt a responsibility to set a positive example for other teacher candidates. “We cannot be the group to marginalize other groups because we know what it feels like to be marginalized. And so, we have to go into our classrooms respecting anyone and everyone.”

Hoff explains that before teachers can form strong connections with their students, they must know themselves. If a teacher possesses biases about any student population, their teaching practices can function from those biases.

To overcome such obstacles, faculty incorporate as many real-world experiences into their instruction as possible. Assistant Professor Shamaine Bertrand, in coordination with NCUE, redesigned one of her courses with an urban focus. The class was just one of almost 100 courses to undergo a makeover the past 15 years.

Bertrand collaborated with fellow Assistant Professor Erin Quast to empower teacher candidates to become change agents for a high-poverty, diverse school in Decatur. The experience was increasingly immersive. They first introduced themselves to parents and school representatives through letters.

They followed up with trips to Decatur for individual meetings. Finally, the candidates sat down with all stakeholders and brainstormed an idea for a project that could add value to the school. At the end of the semester, Bertrand’s students executed their project and presented it to the community.

“We taught them, step by step, how to build community and how to build relationships with parents, students, and administrators,” Bertrand said. “When you see issues happening in schools, this is how you can choose to make a difference.”

These types of experiences have been vital to uncovering Redbird educators’ interests and abilities for serving diverse urban schools, as alumni Lizzy Carroll ’17 and Rachel Henry ’16 can attest. They are special education teachers working at Clara Barton Elementary School in Auburn Gresham, located on Chicago’s west side.

“I decided to teach in an urban setting after seeing the injustices that communities of color are facing,” Carroll said. “I see the inequalities in education as the biggest disadvantage for our students of color, and I believe that every student deserves equitable educational opportunities regardless of their neighborhood, socioeconomic status, or background. I truly believe in the power of a quality education.”

While Carroll and Henry wanted to be teachers for much of their lives, they did not expect their paths to lead to a Chicago neighborhood. They describe the neighborhoods where they grew up as lacking in diversity and offering an abundance of resources, such as grocery stores and health care facilities. Many of their students do not have such access. Henry pointed out the dissonance between her experience and those of her students.

“It was a really shocking and shameful ‘aha’ moment,” Henry said. “I started to volunteer at schools in the Bloomington area that had lower income and diverse students.” She touts her experience in Mustian’s INFUSE sequence as a driving force for her success as an educator.

While Mustian recognizes many Redbirds will not go on to teach in urban environments, the courses are designed to help candidates recognize the assets of students and communities. This makes the curricula applicable to all schools and all students. The coursework also dispels the misconception some candidates have—that they do not need to worry about the concept of diversity in their classrooms if they are returning to monolingual, monocultural environments.

“The truth is that we know those types of classrooms are becoming less common in a hurry,” Mustian said. “But even in the most homogeneous classroom, students need to learn about other cultures, other worlds, and other peoples’ lived experiences.”

While topics of diversity, social justice, and equity are universally recognized as important in educator preparation programs at Illinois State, there is perhaps equal agreement about the need for continuous curricular enhancements.

University President Larry Dietz has shared that “The largest room is the room for improvement” when challenging the campus community to strive for excellence. The saying is apt in this context. The complex environment for supporting future educators, as well as their students, is not easily navigated amid changing policies, narrowing budgets, and growing expectations for student performance across P–20 education. Teacher education programs, however, possess a history of resolve surpassing most. The collective unit has proven itself up to the task for 162 years, and counting.