Winter solstice falls on December 21 in 2020, when the night is longer than on any other day of the year. Celebrating the winter solstice was an important event in Shakespeare’s time, when cold and starvation could be life-threatening. It marked the halfway point of the deep winter, reminding people to steel themselves for the harsh, lean days to come. But it also was a way to set their sights on the new spring.

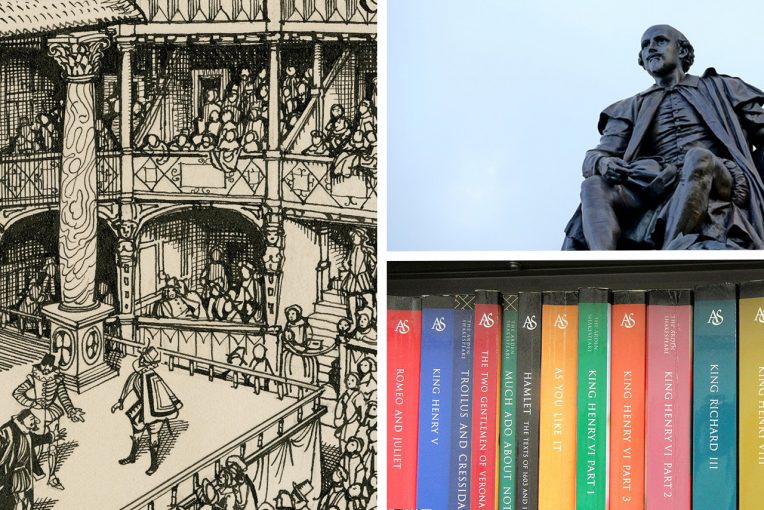

What better way to get through the bleakness of our current winter than reading some Shakespeare, preferably with a hot drink in hand? This article explores some of the instances in which the word winter appears in Shakespeare’s plays. What images and ideas are associated with this frosty season? What did winter mean to Shakespeare?

This past fall, the School of Theatre and Dance presented a Zoom virtual production of Richard III, which begins with Richard’s famous line: “Now is the winter of our discontent / Made glorious summer by this sun of York.” Shakespeare slips in a pun, replacing son with sun, but the main image is of summer triumphing over winter: a new age of order and prosperity following a bloody and chaotic civil war (at least in theory). Here, winter represents adversity and bitterness—something that you have to grit your teeth and overcome. As such, the season was a common symbol for the greatest obstacles in human life and society. In As You Like It, Amiens sings a song that begins with “Blow, blow, thou winter wind,” comparing the inclement weather to “man’s ingratitude.” Notably, Shakespeare inserts this somber tune right after Jacques’s “All the world’s a stage” monologue, threading together Jacques’s melancholy outlook on life, Duke Senior’s misfortune of being usurped by his brother, and the gloomiest of seasons. In other plays and poems, winter takes on human attributes, described as being “angry,” “furious,” “churlish,” and “hideous.”

In some pagan traditions, the winter solstice kicks off the Twelve Days of Yule, which influenced the Twelve Days of Christmas in the Christian calendar. The Twelve Days of Christmas culminates in Epiphany’s Eve (January 5 or 6), also known as Twelfth Night. Scholars think that Shakespeare may have written the play Twelfth Night for a court performance during the Twelfth Night festivities in January 1601. The play’s atmosphere—lush, carefree, and romantic—draws a stark contrast to what was probably the coldest and hungriest part of the year. Perhaps the long winter was filled with festivals and feasts because people craved emotional sustenance as much as hot food in their bellies. They wanted to believe in the dead of winter that warmer and brighter days are on the horizon.

Winter was also seen as a time for fanciful stories in Shakespeare’s time, maybe because they provided a momentary diversion from the cold. In Macbeth, Lady Macbeth chides her husband’s superstitious fear of ghosts and demons by comparing it to “A woman’s story at a winter’s fire / Authorized by her grandam.” Of course, the irony is that this is no fairy tale; Macbeth actually sees Banquo’s ghost. This image of a fireside story in winter is at the heart of The Winter’s Tale, one of two Shakespeare plays that have a season in its title (the other, of course, being A Midsummer Night’s Dream). Early in the play, Queen Hermione of Sicilia asks her son Mamillius and tell her a story. Mamillius asks, “Merry or sad shall’t be?” to which Hermione responds, “As merry as you will.” But Mamillius retorts, “A sad tale’s best for winter. I have one / Of sprites and goblins.” The Winter’s Tale itself could be one of these tall tales that helped people endure the long winter nights, full of mysterious oracles and princesses living as shepherdesses and statues coming to life.

Mamillius says that the winter is a time specifically for sad tales. It is as if he is subconsciously aware of the tragedy that will befall him and his mother right after this scene, when King Leontes falsely accuses Hermione of adultery and Mamillius dies abruptly as divine punishment. The first three acts of The Winter’s Tale, all set in winter, constitute a mini-tragedy that ends in suffering and remorse for Leontes. He loses his entire family, including Hermione who reportedly dies of heartache, as well as his newborn daughter Perdita, banished to Bohemian wilderness because Leontes wrongly assumed that she was not his child. But as we have seen, winter for Shakespeare also represents our capacity to endure hardship and keep faith that better days are ahead. After the allegorical figure of Time appears to announce a sixteen-year jump in the story, Act 4 picks up in the midst of a sheepshearing festival, which tells us that the rest of the play is set in summer. At the end of the play, Shakespeare ventures to strain his audience’s suspension of disbelief by having Hermione miraculously returns to life to be reunited with her atoning husband and long-lost daughter. Despite the common belief that sad stories best suit for winter, The Winter’s Tale ends with a glimmer of hope that warmer weather will eventually come if we can make it through these dark, gloomy days.

As we brace for additional waves of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic this winter, we might take Shakespeare’s hopeful spirit to heart, reminding ourselves that there is light at the end of the tunnel. This is not necessarily blind optimism; the absence of Mamillius and other characters who fell victim to Leontes’s wrath is noticeable at the end of The Winter’s Tale, despite the uplifting conclusion. Instead, Shakespeare seems more interested in our ability to withstand the plight of winter through resilience and solace. How do you imagine this winter ending? Speaking personally, I am spending these cold months dreaming of a summer when it is safe to go outside, meet other people, and maybe even enjoy some live theatre again.

Beyond the Stage is an article series on the dramaturgy of Shakespeare productions in the current season. These articles explore the plays from a wide range of perspectives, from history and literary criticism on the original works to interviews with directors and creative teams.