Festival Dramaturg Kee-Yoon Nahm spoke with director Rebekah Scallet about the upcoming production of William Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale at the Illinois Shakespeare Festival (ISF).

Kee-Yoon Nahm (KN): Some of our patrons may be less familiar with The Winter’s Tale. Would you talk about the things you find interesting about the play?

Rebekah Scallet (RS): Sure. Some people classify it as one of the problems plays, which I think is unfair. But then again, as a director, I have always been drawn to the so-called “problem plays.” What is really the problem, and is it a problem? I do not think there are problems with The Winter’s Tale, although it stands out among Shakespeare’s plays. One difficult thing about the play, which is also one of the things that I love, is that you almost have two plays in one. The play begins in Sicilia, where it is focused on Leontes and his jealousy. We watch him unravel. And then we go to Bohemia, where we see a completely different plot and world. All of a sudden, it is a comedy and a romance. The two plots are brought together with magic. It can be tricky uniting these worlds in a way that feels satisfying for the audience. But it is also what makes the play really fun.

KN: Many of Shakespeare’s plays blend the comedic and the tragic, but I do not think there is another play that is cut straight down the middle like The Winter’s Tale. How will you handle that? Are the two halves of the play like opposite forces that you want to reconcile?

RS: My plan is to just go where the play leads. I think that Shakespeare is exploring these opposites. It is interesting that you have the two kings of Sicilia and Bohemia who are so similar, but Shakespeare has written it so that they are from very different worlds. Also, while there is comic relief in a lot of Shakespeare’s tragedies, the first half of The Winter’s Tale is unrelenting with very little comic relief. Then, when you get to Bohemia, we can breathe again and enjoy things and laugh. It feels so good. So I really want to lean into the differences between the two worlds.

KN: I like what you said about going where the play takes you. We think of the play as being separated into these two realms, Sicilia and Bohemia. But there is actually some travel between the two settings. It is important that certain characters move from one kingdom to the other to advance the plot.

RS: Right. As we start the design process, we have been thinking about how the world of Bohemia comes to Sicilia in the end of the play. Perdita returns to her birthplace after sixteen years, but she has been raised in a different world from that of her parents. She has been raised by shepherds. I think she brings with her the looseness, freedom, and passion that she was able to explore through her upbringing. When the two worlds come together, and we have this moment of forgiveness at the end of the play, it is also about Leontes changing and being open to these new ideas. And part of that comes from what Perdita brings with her.

KN: Would you also talk about the play’s journey through time? Many Shakespeare plays have leaps in time, but The Winter’s Tale is unique in that Shakespeare felt the need to justify the passage of time by having this chorus-like figure.

RS: Yes, we have Time come out and speak to the audience. Time is personified in other Shakespeare plays, but it is usually characters talking to Time or railing against Time. But here, Time actually gets to talk to us and help move the story along. We have this huge time jump of sixteen years, which is an important part of the story in that the baby Perdita has grown up into a young woman. But also, I think about the time that it takes for Leontes to mourn and repent for his behavior. That is another hard thing about the play. For the audience, it is only an hour or two from when Leontes condemns his wife to death to the final scene. And so, we may ask: how could Hermione forgive him for something that we just witnessed a while ago? I think that is part of the reason we see Time. This figure helps us accept that Leontes has been repenting and visiting Hermione’s grave—becoming a different person over a very long period of time. This change does not happen overnight in him.

KN: Continuing the topic of “problems” in the play, I think that Shakespeare is challenging our credibility in the play’s events. Why is Leontes suddenly jealous of his wife? Shakespeare does not give us a clear reason. There are also moments that require theatrical imagination, such as the sixteen-year time jump, the abrupt genre shift, the bear in the stage directions, and, of course, the statue coming to life in the end. How will you help us believe in the things we see onstage?

RS: In a way, the characters on stage mirror the audience’s experience of watching the play. When Leontes and the others see the statue, Paulina asks them to suspend their disbelief, to just go with it. This is a statue that is coming to life, and we are all going to believe in this. I think the same thing happens when we go to the theatre. We see things that are not necessarily realistic, like a bear coming onstage and consuming a character. But that is why we go to the theatre or the movies. It is to have those experiences of being transported and to believe in things that in real life might be hard to believe. I think The Winter’s Tale is also a play about repentance and forgiveness. It is about the amazing step that Hermione might possibly take at the end of the play in choosing to forgive Leontes. Of course, it is also interesting that Hermione does not actually have language in the play that forgives Leontes. We have to make our own interpretation. But at least we do see that the family comes together. And to believe that kind of forgiveness is possible, that is another act of faith. To choose to make a life together is an act of faith in the same way we are asked to believe that a statute can come to life. Every marriage is an act of faith in that way, right? There is no proof that it will all work out.

“To choose to make a life together is an act of faith in the same way we are asked to believe that a statute can come to life.”

KN: Right. I agree that the play does not only test the faith of characters such as Leontes, but also the audience to some degree, acknowledging that you often have to rely on leaps of faith in human relationships. To connect with someone, sometimes you have to defy doubt and go with your heart.

RS: You mentioned the fact that we do not really know why Leontes is jealous. Shakespeare does not give us a reason; it just happens. Part of me thinks it does not really matter. It does not matter if Hermione looked at Polixenes the wrong way or if there was some other reason for Leontes’ suspicion. The important thing is that the jealousy exists. The fact that it may not be motivated by something concrete makes it all the more terrifying. There is something disturbing taking place inside of Leontes’ brain, and he cannot shake it away.

KN: Would you talk more about Leontes’ psychological state at the beginning of the play?

RS: The more I read the play, I feel that Leones is tormented by an idea that has taken hold of him. A seed has been planted in his brain. It sprouts and grows until it causes a kind of psychic break. I really do think he is suffering from a mental illness. It is not just something he is able to snap out of. Also, Leontes is surrounded by a lot of people who are not really standing up to him. Everybody sees that he is having mental problems, but they do not stop him from sentencing Hermione to death and so on. Camillo decides to run away rather than kill Polixenes as he is asked to do. It is really hard to stand up to the King. So Leontes is allowed to continue on this path. Paulina is the exception, the one person who confronts him. But ultimately, she does not have the power to do anything.

KN: I am interested to see that court dynamic play out in the production. I want to switch gears and talk about the unique situation we are in right now because of the pandemic. You are working under unusual production limitations. What are some of the challenges that you are facing?

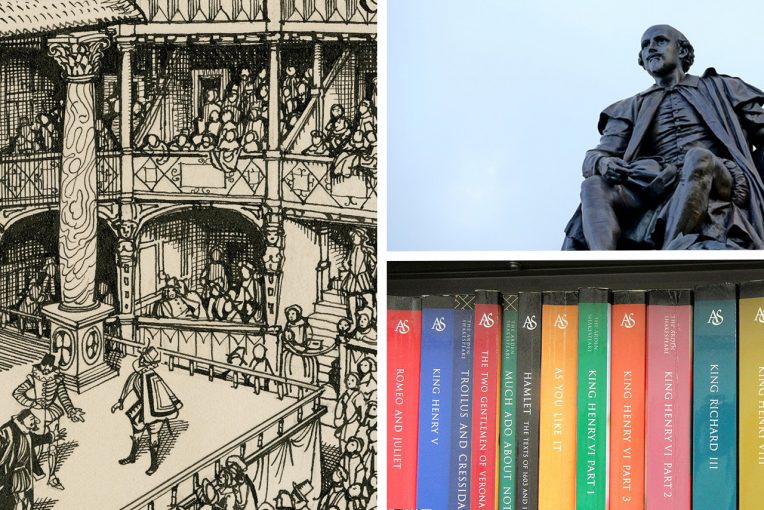

RS: First of all, I am excited to be able to do a play in the time of COVID-19. I miss that live theatre experience. It has been hard to be away from it. So, I am excited to get back to it. As I said earlier, The Winter’s Tale is a play that, in a lot of ways, is about the beauty of believing in the theatrical experience. I love that it will be many people’s entry back into theatre. But we are not done yet with the pandemic, so we will have to make some changes. As of now, our actors will have to be masked if they are standing close together, and the cast will be smaller than usual for ISF. For the most part, I will try to stage the play so that the actors are socially distanced from each other and will not have to be masked. This way, we can see their faces and mouths. We will be masked in rehearsals, and actors will not be able to share props or exchange costume pieces. Figuring out how to deal with all those things is definitely challenging. But as a director, I have always felt that challenges are great opportunities for creativity. We know that Shakespeare had to deal with production limitations in his time, and I think we see a lot of creativity in his plays in response to that.

“The Winter’s Tale is a play that, in a lot of ways, is about the beauty of believing in the theatrical experience. I love that it will be many people’s entry back into theatre.”

KN: Right, when I read some of the more outlandish moments in The Winter’s Tale, such as the bear or the statue coming to life, I have to remind myself that Shakespeare’s company did it on a bare stage with virtually nothing. That is how it was meant to be done. Is there a larger concept for your production that you can share at this point in the process?

RS: I came up with the idea of framing The Winter’s Tale as a fairy tale. A “winter’s tale” in Shakespeare’s time referred to an old tale that that people would tell by a fire on a winter night. We are not setting this fairy tale in any specific time period, but rather imagining it in the land of “long ago” and “far away.” And it is a story that has been told over and over again, as so many of Shakespeare’s plays have. This fairytale frame helps us imagine our actors as storytellers who are presenting this tale. Many of the actors play multiple roles, switching quickly from one character to another. So, it is about embracing the changes that we are making to the play. I am also starting the play with a new prologue that introduces some of the COVID-19 restrictions that we will have so that we can tell everyone: “Hey, this is where we are as we tell you this story. There might be a mask on but we are going with it.”

KN: I imagine this prologue can also be about inviting the audience into a space where stories are shared.

RS: Yes, absolutely. We are inviting the audience to go on the journey with us and believe in it.

KN: I think that after a year of experiencing stories mostly through screens, it will be wonderful to have a space where audiences can project their imaginations and fill in the blanks themselves. I am already excited to be there. As a final question, would you talk about how COVID-19 has impacted you as a theatre artist this past year?

RS: It is interesting for me because I left my position as Producing Artistic Director for the Arkansas Shakespeare Theatre right at the beginning of the pandemic. My family and I had decided to move to a new city and start some new adventures. So just as the pandemic was happening, I left a full-time job, moved to a new home, and had my access to the art taken away all at once. That has been difficult—to not have opportunities to be creative and get to work with my fellow artists. I was scheduled to direct As You Like It last summer, but it did not happen. I am heading into my longest span ever without being in a rehearsal room with actors. There have been the occasional Zoom project and opportunities to do things, but it has been hard. For me, theatre is such a unique art form in that it is so collaborative. The real joy for me has always been about working with other people, being in the room together with designers and actors, watching an audience respond to your work. All of those human connections have been missing for a long time now. So, I cannot wait.

KN: Yes, I feel that we have all been hibernating creatively to some degree, and we are finally ready to wake up.

RS: Absolutely. It is not the same when you are by yourself or on a screen. I am ready to get back to the theatre.