This article is a culmination of research made possible by grant funding from the Council on Library and Information Resources. The collaborative project, Step Right Up: Digitizing Over 100 Years of Circus Route Books, digitized and made accessible over 300 of the 400 known distinct route books in existence held by Milner Library, Circus World Museum, and The Ringling Archives.

While researching Black sideshow musicians for the grant project’s upcoming digital exhibit Agency through Otherness: Portraits of Performers in Circus Route Books, 1875-1925, it became apparent there was another story that needed to be told: the legacy of Ephraim Williams, the world’s first Black circus owner, told in the context of what Black circus performers faced before, during, and after his time.

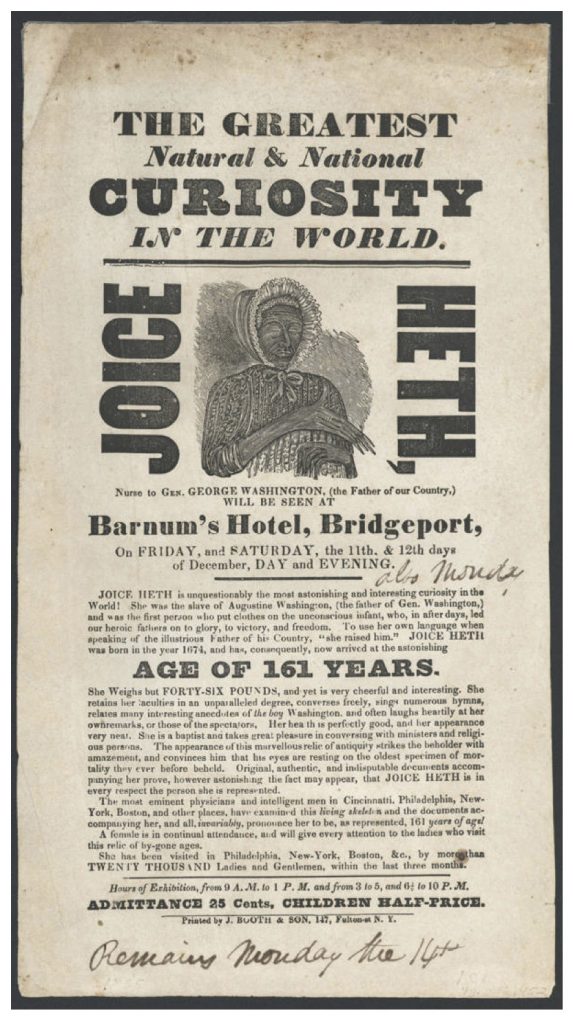

August 6, 1835, Hotel Barnum, Bridgeport, Connecticut

Even though slavery had been outlawed by New York State, P. T. Barnum was a slaveowner who used a loophole to ‘rent’ Joice Heth. Heth was then exhibited for profit by Barnum under the false claim that she was the 161-year-old caregiver of George Washington. He made her “one of the most publicly subjugated females of the 19th century.” Heth died in February of 1836, but “even in death Barnum robbed her of dignity … in a profit-driven scheme supposedly to verify her age, hundreds of spectators paid fifty cents to Barnum to witness the dissection of her body.” His first foray into trafficking people as curiosities complete, Barnum went on to form perhaps the most successful circus in history.

“By giving blacks the most subservient positions within the lowest division of labor, circus management not only procured the cheapest labor possible, they also avoided angering their white employees,” said Micah Childress in the article Life Beyond the Big Top: African American and Female Circus, 1860-1920. “This is one of the reasons employers outside of amusement often refused to promote or hire blacks beyond the lowest positions. In the Gilded Age, if African Americans could secure work, their employers limited them to certain tasks. In the railroad industry, for example, whites deliberately barred blacks from moving beyond the post of porter…”

Early 1880s, Appleton, Wis.

Ephraim Williams worked as a porter and shoeshine at Briggs Hotel. Here on the Fox River was a railroad yard, bustling with circus cars and lumber flatbeds. Baraboo, to the west, was the home of the newly founded Ringling Brothers Circus. To the north was logging land. Eph had a fascination for the tent shows brought by the trains. He began practicing magic tricks.

He began to plan.

Because Gilded Age legal culture tilted so heavily in favor of [corporations], circus employees had to take care of themselves as a group … in the last decade of the nineteenth century they formed mutual aid organizations … Basically barred from entering the ranks of performers and typically relegated to the lowest-paying and least-skilled labor practically precluded black circusmen from the funds they needed to form and operate their own mutual aid societies.

— Micah Childress

And yet they did form. Forced into the annex, paid insulting wages, squeezed into the crime portions of the newspapers, and forbidden from secret societies, African Americans continued to create their own spaces after emancipation, a legislation that did not solve segregation. In addition to the Black press and Black fraternal organizations, African Americans began to form their own fairs and carnivals around the same time that the first Black bandleaders were permitted to perform in sideshows and began planning their trajectory to company ownership.

1885, Appleton, Wis.

As soon as he had enough money saved, Eph “purchased a black stallion colt. He trained the horse to ‘solve’ arithmetic problems” by “stomping out the correct number with its hoof.” The duo became a popular opera house attraction. In the spring, “he took his production on the road and headed to northern Wisconsin to entertain workers at the lumberjack camps.”

Eph was going to start his own circus.

“I ran across this show from the turn of the century called Silas Green from New Orleans starring Bessie Smith,” said Cal Dupree, UniverSOUL Circus Ringmaster. “It had everything: tap dancing, animal acts, comedy skits, even a chorus line from Venezuela. It was brilliant, and it drew black and white people, even though it was all about black talent. … Let’s just go ahead a do a damn circus!”

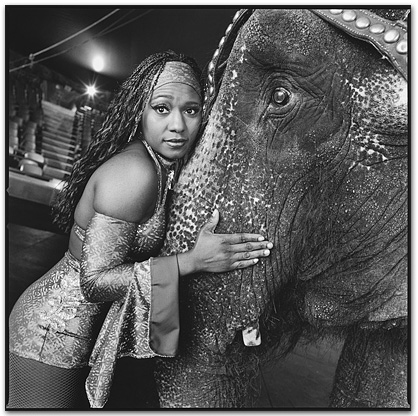

March 20, 1999, Hard Rock Stadium, Fla.

Margo Porter is an elephant trainer with UniverSOUL Circus. Dressed in a sparkling blue majorette outfit, she rides atop Anna Mae. UniverSOUL Circus was “the nation’s first all-black circus in nearly a century” when it opened in Atlanta in 1994, and is the only Black-owned circus today.

“It’s all Black and that is a really exciting thing to be a part of,” Porter said of UniverSOUL. “At other circuses you don’t see too many of us out front. You might see us shoveling up the poop but not doing the glamorous stuff. Soul circus really spotlights us.”

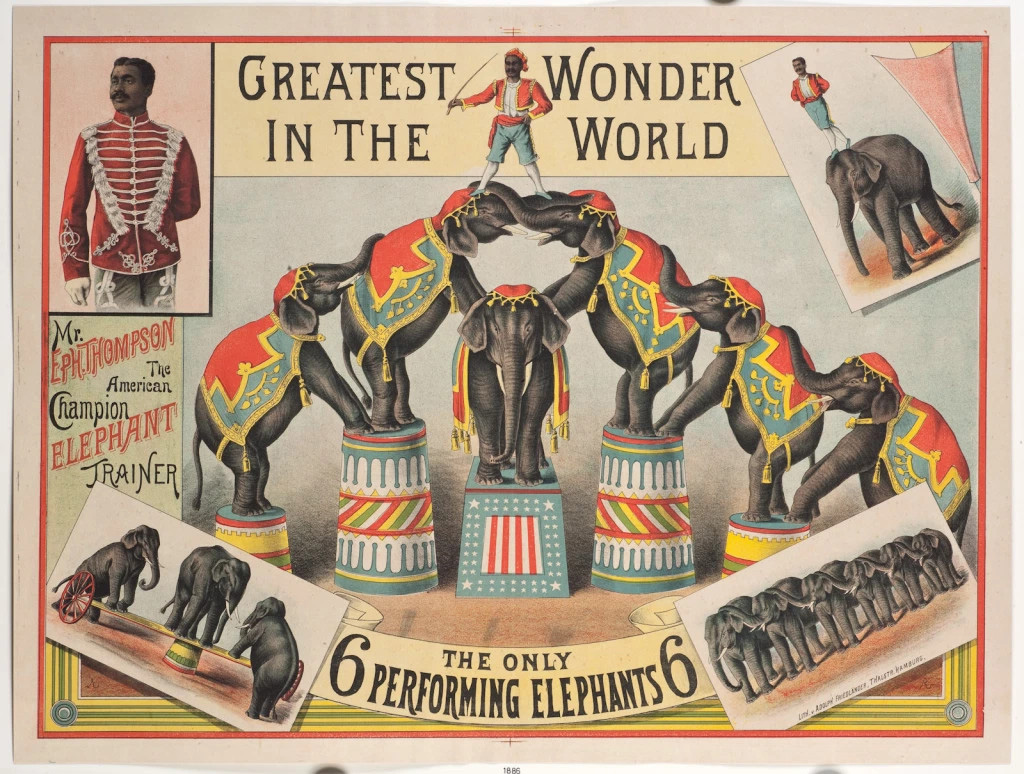

Ephraim Thompson was arguably the best elephant trainer there ever was. He was born in Canada in 1859, where his parents had fled to escape slavery. They later settled in Ypsilanti, where Thompson became fascinated by the traveling circuses as the Forepaugh show routed through in May of 1873. After working as a cook for Hotel Forepaugh, he began porting water for elephants, eventually becoming the trainer and caretaker of the large elephant brigade with the Forepaugh show. Despite his obvious talents, he was not allowed to perform in the big tent. Instead, Adam Forepaugh, Jr., got the credit; story goes that he was rough with the elephants, as they were not used to him, having been trained by Thompson.

So, Ephraim Thompson started his own show.

“It was only through ingenuity and perseverance that these versatile and resilient performers of color found a successful if limited place within the circus hierarchy in the United States,” said Vanessa Toulmin of Early Popular Visual Culture. “The international success of Eph Thompson, the renowned African American elephant trainer in France, Germany and England was not achieved until he left the United States as his talent was restricted within a tightly segregated environment.”

He received great acclaim in Europe, where entertainment, though still conforming “to racial stereotyping so that the circus only entrenched the prevailing social norms,” had a more diverse stage. “We’ve always been there,” Iverson said, noting that one of P. T. Barnum’s earliest attractions was an elderly African-American woman who, he claimed, was George Washington’s nursemaid. Historically, the circus is, and continues to be, the province of white Europeans.

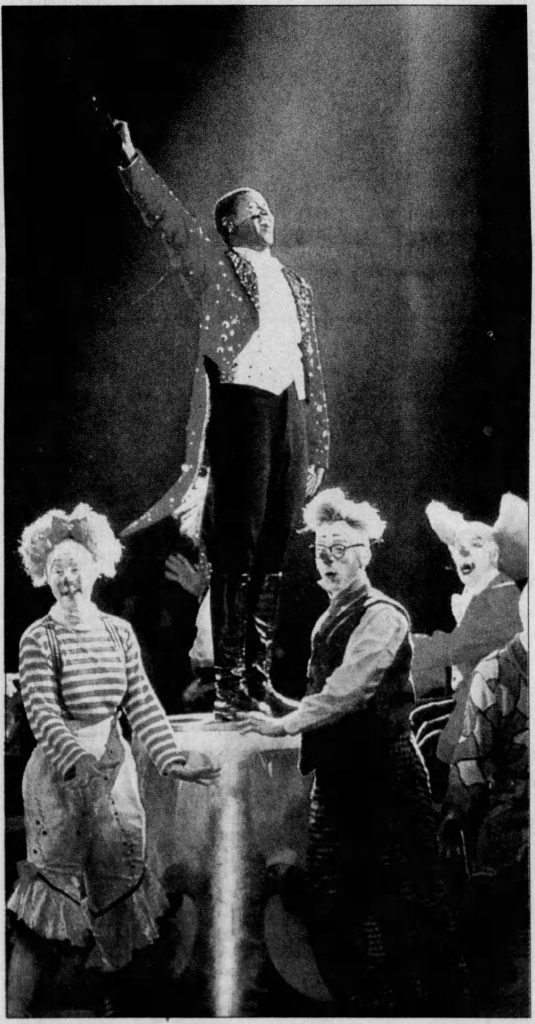

At 23, Johnathan Lee Iverson is the youngest ringmaster to host Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. He is also the first African American in the role. “We have the most diverse audience in any genre of entertainment. No genre of entertainment has greater diversity of people that come to patronize its shows than Ringling Brothers,” said Iverson.

“No. Black families didn’t go to the circus. Well, my family didn’t. You heard about it but you never actually went,” said Margo Porter.

There is a relationship between the performer and the audience. The extent to which this relationship is one of Othering is molded by marketing, culture, shared experience (or lack thereof), and expectations. Just as 19th century circus owners and bandleaders tailored their spectacles to what the gaze desires, so do 20th century circuses. It’s not only the featured performers at UniverSOUL that differ from previous decades.

Although the performers felt more freedom entertaining in an environment more geared to their culture, music, etc., Dupree believes they also felt more pressure performing in front of a mostly black audience. “Having your own folks in the audience, it’s a little different. We have a way of creating when we’re in front of our own,” he said.

And that way of creating is probably quite different from what Bobby Cole, one of the greatest early 19th-century comedians who performed alongside Williams’ pony show, had to do. He was “particularly known for his appearance in a clown’s white-face, in an era when even blacks were blackening their faces for the stereotypical amusement of all.”

BIPOC are an integral part of the circus, but were almost never in such an elevated role as ringmaster or owner. The very origin of the circus in America is white Europeans exhibiting people of color as the Other. With the big top brimming with whites in blackface, African Americans were either “relegated to the sideshow tent and generally given the duty to depict an African or a monkey-man combination” or the “category of general laborer” at the bottom of the circus social pyramid.

Ephraim Williams, however, had “no intention of being relegated to freak status in a sideshow.”

“When the horse show became a success, Williams took his venture a step further. Decked out in a tuxedo, top hat and cane, Williams traveled across Northern Wisconsin, playing to the lumberjacks.” Over the next 15 years he ran three circuses: the Ferguson & Williams Monster Show, Professor Williams Consolidated American & German Railroad Shows, and Professor Ephraim Williams Great Northern Circus.

Most circuses hit a snag, and often it’s a hole they can’t climb out of. By the 1902, Eph wasn’t doing so hot. “His fall from prominence was probably aggravated by white resistance to the initial success of this upstart black proprietor, who was performing with white employees, and for white audience.” He spent most of the first decade of the century performing in Black dramatic companies, like Thompson, Williams also traveled to Europe to seek more fame than available to him in the United States. But by 1910, “Eph had once more returned to the circus: He had become the founder, sole owner, and manager of Prof. Eph Williams’ Famous Troubadours, touring an all-black tent show called ‘Silas Green from New Orleans.’ This circus-revue played one-night stands throughout the South, and became one of the longest-lasting tent shows in American show-business history.

July 2009, Baraboo, Wis.

“There aren’t any Black people in it. That’s not the way the circus was.”

– Cecilia Gilbert, Gilbert & Jones troupe

Cecilia and Shirley Gilbert are at The Circus World Museum. They’re working with staff to “re-create the costumes that made the [1880s] troupe so eye-popping: Miss Mary Mack’s frills and big red buttons, Liza Jane’s ribbon-festooned wig.” These characters are recreations of the “Gilbert & Jones” segment of the Great Circus Parades from 1986 to 2003, which in turn was a reimagination of characters from “ancient African culture and American slave days.” It was Cecilia who in 1984 realized that their parade was exclusive and anti-historical.

So, she made her own troupe.

Alongside the Gilbert & Jones troupe is The Black P. T. Barnum himself, as portrayed by Milwaukee showman Andre Lee Ellis in a top hat and cane. “In his day, dressing like this gave Williams a powerful feeling. Now we want people to feel this energy again … A lot of African-American people don’t know about Williams and these characters,” said Cecilia Gilbert. “We’ve seen the joy they’ve brought to people’s faces before in parades, and we want to bring the joy back again.”

More on the Circus Route Book Project

- How a former employee found her passion working with circus route books

- The Life of Circus Lady Josephine Demott

- Milner Library preserves vital history with the digitization of circus route books

- Milner Library receives $268,000 grant to save circus history

Article Sources

Benjamin, Jody A. “Step Right Up To Circus Where Elephants Boogie.” South Florida Sun Sentinel, March 20, 1999. https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1999-03-20-9903190497-story.html.

Childress, Micah. “Life Beyond the Big Top: African American and Female Circusfolk, 1860-1920.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 15 (2016): 176-196. https://doi:10.1017/S1537781415000250.

“Eph Williams: The Legend of the Tent.” Daily News, May 4, 1997. https://www.newspapers.com/image/475733789.

Childress, Micah. “Life Beyond the Big Top: African American and Female Circusfolk, 1860-1920,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 15 (2016): 179, https://doi:10.1017/S1537781415000250.

Darrow, Chuck. “Under the Big Top: Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus Comes to Town with a New Ringmaster.” Courier-Post, April 13, 1999. https://www.newspapers.com/image/183655085.

Feingold, Russ. “African-American circus pioneer in Wisconsin.” The Dunn County News, March 3, 1999. https://www.newspapers.com/image/542344920.

Haynes, Monica L. “UniverSoul Appeal: Circus of Black Performers Brings Big Top to Pittsburg.” Pittsburg Post-Gazette, July 14, 1999. https://www.newspapers.com/image/94406350.

Hoh, LaVahn G. Step right Up!: The Adventure of Circus in America. White Hall, Virginia: Betterway Publications, 1990. https://archive.org/details/steprightupadven0000hohl.

Jackson, Janet Alston. “African American Circus Ringmaster.” Los Angeles Sentinel, July 8, 2010. https://lasentinel.net/african-american-circus-ringmaster.html.

LaVahn G. Hoh, Step Right Up!: The Adventure of Circus in America (White Hall, Virginia: Betterway Publications, 1990), 68.

Loohauis-Bennett, Jackie. “Troupe Tells Story of Black Performers.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 7, 2009. http://archive.jsonline.com/news/milwaukee/49875812.html.

Ridenour, George. “Eph Thompson – Elephant Trainer.” Ypsilanti Gleanings (Spring 2010). https://aadl.org/ypsigleanings/35681.

Toulmin, Vanessa. “Black Circus Performers in Victorian Britain.” Early Popular Visual Culture 16, no. 3 (2018): 267-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460654.2019.1569854.

Williams, Jeffrey E. “The Lord of the Big Top.” Daily News, May 4, 1997. https://www.newspapers.com/image/475739237.