A pair of young lovers fall in love at first sight. Their wedding is officiated by a friar of the Franciscan Order. Later, the friar intervenes when misfortune strikes the couple, coming up with a plan to fake the death of the new bride. Does this sound familiar? You may be thinking of Friar Lawrence in Romeo and Juliet, who gives Juliet Capulet the sleeping potion so that she can live happily with Romeo Montague. But this description also applies to Friar Francis in Much Ado About Nothing, who devises a plan to falsely announce Hero’s death after Claudio publicly accuses her of dishonesty. Francis’ plan actually works: Claudio and Don Pedro eventually repent their ungrounded attack on Hero. Although Francis is less developed than the better-known character in Romeo and Juliet, he directly impacts the comedy’s happy ending through his insight and quick thinking. Who is this friar, and what might have inspired Shakespeare to create such a character?

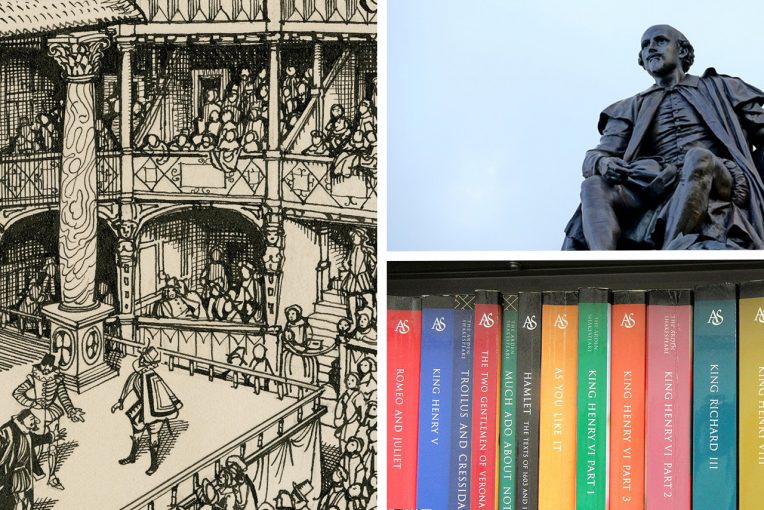

Franciscan friars had become rare sights in England by the time that Shakespeare wrote these plays in the final decade of the 16th century. Monasteries and friaries were once powerful institutions in medieval England, amassing wealth and exerting influence over local communities. This all changed in the late 1530s when Henry VIII launched an extensive campaign to dissolve monasteries and seize their property, following his self-appointment as the Supreme Head of the Church of England in 1531. One of those dissolved monasteries, the Blackfriars Priory in London, later became the site of the Blackfriars Theatre, which the King’s Men sometimes used as a secondary, indoor performing space. (Blackfriars refers to the Dominican order, named such for the color of their robes; Franciscans were likewise called greyfriars.) While names such as Blackfriars continued to be used after the 1530s, the number of friars in England fell sharply as a result of these events. Many members of these disenfranchised orders moved to Catholic countries to escape persecution—such as Italy, where both Romeo and Juliet and Much Ado About Nothing are set. Given this context, it is interesting that Shakespeare chose to write characters based on a religious figure that had all but faded away in his society.

Shakespeare is notorious for recycling story elements across his dramas, so it is not unusual for the same character type to appear in multiple plays. But what is perhaps unusual, according to some scholars, is Shakespeare’s positive depiction of friars who were often distrusted and ridiculed in 16th England. The Protestant Reformation partly fueled negative attitudes towards monks and monasteries; other works of literature and theatre during the time portray these ascetic, robed figures as hypocrites, conmen, or dabblers in dark magic. Yet for some reason, Shakespeare chose to portray his friars as exceptionally kind-hearted and wise figures in a world full of flawed people. Although we cannot know for sure, it is possible that Shakespeare risked upsetting some of his audience in doing so.

Interestingly, all of Shakespeare’s friar characters are not above resorting to a little deceit for the sake of good. As mentioned before, both Lawrence and Francis fool others into thinking that a young woman has died in order to save her. Kenneth Colston argues that Shakespeare’s friars share “an ability to bring good from evil, to see innocence when others see guilt, to act irregularly, even duplicitously, in order to solve a sudden crisis made by human wickedness.” [1] In other words, although these characters undoubtedly have good motives, they bear traces of the deceitful Catholic monk stereotype that was prevalent at the time. Furthermore, Colston notes that these friars work against misguided nobles in each play, undermining Lord and Lady Capulet’s rights as parents or Don Pedro’s princely authority. In this way, they become symbols of the tension between religious and secular power, quietly exerting influence over who marries whom. It is worth remembering here that Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church was caused by a disagreement over own his marriage: Henry VIII wanted to divorce Catherine of Aragon; the Pope said no.

This interpretation does not suggest that these friars are somehow manipulative or self-serving for changing the course of the story. Rather, they serve as the moral centers of their respective plays. In Much Ado About Nothing, Francis is the first character to recognize Hero’s innocence after Claudio’s shocking condemnation at the altar. He says:

Hear me a little, For I have only silent been so long, And given way unto this course of fortune, By noting of the lady. I have marked A thousand blushing apparitions To start into her face, a thousand innocent shames In angel whiteness beat away those blushes, And in her eye there hath appeared a fire To burn the errors that these princes hold Against her maiden truth. Call me a fool, Trust not my reading nor my observations, Which with experimental seal doth warrant The tenor of my book; trust not my age, My reverence, calling, nor divinity, If this sweet lady lie not guiltless here Under some biting error (IV.i.164–179).

In a previous article, I mentioned the pun in the title between “nothing” and “noting.” Francis describes his careful “noting” of Hero’s appearance, which ultimately convinces him of her innate virtue. In other words, the friar has the capacity to see someone’s truth in a world full of deceptive surfaces, something that almost all the other characters in the play lack. He stakes his knowledge and experience—his very reputation—on this belief, whereas Hero’s own family members jump to conclusions based on Claudio’s accusation. Moreover, his plan to fake her death has a purpose greater than just moving past this difficult situation. Friar Francis remarks later in the same scene that wants a “greater birth” (IV.i.224) for both Hero and Claudio, seeking to transform these naïve youths into more mature souls. In this way, the fake death plot becomes an occasion for spiritual reckoning.

Francis is first introduced more than halfway through the play, and only appears in a handful of scenes. But think of how different the world of Much Ado About Nothing would be without this religious figure. He is the one that prevents Hero’s story from ending in tragedy. But even if things had somehow worked out between Hero and Claudio, this romantic comedy would have been far less reassuring without his wise intervention. Everything hinges on his decisive actions. And while these monkish characters may almost feel like a cliché to us, it is worth remembering that Shakespeare was working against the norm of his time, turning negative caricatures into benevolent helpers.

[1] Kenneth Colston, “Shakespeare’s Franciscans,” The New Criterion, Vol. 33 (February 2015) 21.