During an uncharacteristically heated exchange with a referee in the late 1970s, Illinois State University women’s basketball head coach Dr. Jill Hutchison, M.S. ’69, confidently asserted from the sideline, “I know I’m right. I wrote the rule!”

An early member of the women’s basketball rules committee, Hutchison shaped the game throughout her 28-year hall of fame career—from spearheading research in support of full-court competition to developing the ball.

Appears InBorn nearly 30 years before Title IX—legislation passed in 1972 that prohibits sex-based discrimination in federally funded education programs and activities—Hutchison is among a revolutionary cohort of trailblazing women from Illinois State who dedicated themselves to rewriting the national narrative of women’s athletics.

Early opportunities

From a young age, Hutchison realized that contrary to social norms, she—a girl—loved playing competitive sports. Finding organized opportunities for girls to compete in the 1950s and 1960s, however, was nearly impossible. Hutchison remembers watching her older brother suit up for little league baseball.

“How come girls don’t get to play?” she wondered.

Hutchison’s high school physical education teacher in Albuquerque, New Mexico—Elvira “Tiny” Vidano ’42—had asked the same question. Unsatisfied with the answer, Vidano took it upon herself to organize ‘sports days’ for girls to play basketball, field hockey, soccer, volleyball, and softball against several schools at one site. An Illinois State Normal University alumna, Vidano was inspired by longtime ISNU physical education teacher and administrator Ester French ’28, who had established the first-ever Illinois Sports Play Day in 1931.

“During ‘sports days,’ when you weren’t playing, you’d officiate. We almost coached ourselves,” Hutchison said. “I thought it was fun.”

Hutchison played basketball as an undergraduate at the University of New Mexico while studying physical education—the only option for women seeking a career in sports. After earning a bachelor’s degree, she taught and coached at a junior high school for one year before beginning work on a master’s at Vidano’s alma mater, Illinois State.

Respected reputation

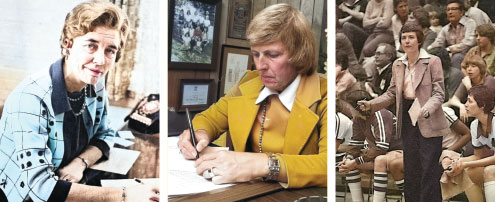

Illinois State Normal University began hosting ‘sports days’ for women in the 1930s. Schools from around the state were invited to compete in soccer and field hockey. Opposite, during the 1970s, a group of trailblazing coaches and administrators at Illinois State oversaw exponential growth in intercollegiate women’s athletics.

Hutchison arrived on ISU’s campus in 1968 to find a thriving Women’s Health and Physical Education Department headed by Dr. Phebe Scott, with hundreds of female majors.

“I think Illinois State did a lot to help this whole business of changing philosophy and changing thoughts about the place of women in sports for the rest of the country,” Scott said in a previous State article. “A number of our students became coaches and administrators in various parts of the country. And I think they did have a lot to do with the rest of the country kind of looking around and saying, ‘I guess this isn’t so bad after all!’”

The influence of Illinois State’s physical education program was profound—from New Mexico to nearby Pekin—where a young Melinda Fischer received physical education instruction from two hall of fame ISNU multisport athletes: Lorene Ramsey ’59, M.S. ’63, and Barbara Waddell ’63, M.S. ’72. Fischer also gained professional advice from Doris Henderson, ISNU’s physical education student teacher supervisor who frequented Pekin High School.

“When I got to high school, Illinois State was just ingrained in my mind,” said Fischer ’72, M.S. ’75, who has been ISU’s hall of fame head softball coach for the past three decades and earned her 1,100th Redbird victory this year. “If you’re going to be a teacher, and you want to play competitive sports, this is where you want to go.”

National impact

As a freshman at Illinois State in 1968-1969, Fischer played field hockey, basketball, and softball. Hutchison was a graduate assistant coach for the basketball and softball teams.

At the time, basketball was a six-player game. Two played half-court defense, two played half-court offense, and two were rovers who could go full-court. There was a long-held theory that women’s hearts were too weak to play full-court basketball, a concept that Hutchison was determined to scientifically debunk through telemetry. For her graduate research project, Hutchison attached electrodes to two players—one of whom was Fischer—and monitored their heart rates as they played a full-court game.

“We were able to show that they could maintain what’s considered a strenuous workout at 180 beats per minute for a prolonged period of time,” Hutchison said. She worked with faculty member Dr. Bob Singer to publish her findings. The Division for Girls and Women’s Sports (DGWS) took notice and asked Hutchison to join the women’s basketball rules committee.

“I presented my research, and it felt good to really make a difference,” Hutchison recalled. She and Fischer made history again in 1969 when the Illinois State softball team qualified for the inaugural Women’s College World Series hosted by the DGWS in Omaha, Nebraska.

“It was the first time ever to do anything like that,” said Fischer, who played shortstop for the Redbird team that finished ‘second in the world.’ “It was a fun group of girls being in a situation where we were successful and wanted to win that championship.”

The following year, Illinois State hosted the first Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (CIAW) National Swimming and Diving Championships at McCormick Pool. Hutchison worked as a timer. Fischer, a Women’s Recreation Association board member, was the meet photographer.

“Me, who didn’t know anything about photography,” Fischer quipped. “That was really special that we were hosting that event at Illinois State. When everything was starting to really develop and really build, we had such strong, powerful female leadership. That meant a lot to them, and enough to them to continue to pursue those opportunities.”

Along with Scott, leadership was provided by Dr. Laurie Mabry. A professor of physical education, Mabry was Illinois State’s first and only director of Women’s Intercollegiate Athletics from 1960-1980. After the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) evolved out of the CIAW in 1971, Mabry and Hutchison organized the nation’s first collegiate basketball championship for women. It was hosted at Illinois State’s Horton Field House in March 1972.

“The fun part about that was setting up the whole structure,” said Hutchison, who had been named ISU’s head women’s basketball coach in 1970. “There were three of us who were responsible for figuring out how to select teams, how to seed teams, how to get officials. We started from pure scratch to do this whole tournament.” The regions they established are still used today.

Hutchison said the tournament was a success and the talent was “amazing,” as it included women’s basketball legend Pat Summit among other future Olympians and Olympic coaches.

Along with developing the national tournament structure, Hutchison joined the AIAW basketball rules committee and later championed the move to a slightly different ball—1 inch smaller in diameter and 1 ounce lighter than the men’s ball to allow for improved ball handling and more efficient scoring.

Title IX becomes law

President Richard Nixon signed Title IX into law on June 23, 1972. Schools had until 1978 to comply with athletics requirements. While the nation underwent a seismic cultural shift in the wake of Title IX, Mabry was called upon to serve as AIAW president in 1975-1976.

“It was certainly a challenging time for me here at ISU, as well as in the AIAW,” Mabry stated in a previous State article. “But Illinois State was well ahead of Title IX back in those days for the Midwest.”

Mabry advocated for Title IX, which was being challenged on the national stage. She testified on behalf of the AIAW before a Congressional committee in opposition to the Tower Amendment. The bill unsuccessfully sought to exempt revenue-producing programs, such as football and men’s basketball, when considering a school’s Title IX compliance.

“I saw being in administration as an opportunity to make changes and be able to do it in a different way than just one coach could.”

Linda Herman

A future hall of fame administrator, Dr. Linda Herman, M.S. ’72, Ed.D. ’83, was hired as the Redbirds’ head volleyball coach in 1975 and recalls Mabry working with Illinois State President Dr. Lloyd Watkins and Dr. David Strand. He was hired as an executive officer in 1978 and held top administrative roles on campus before also becoming president.

“Those people were the first ones on our campus that actually had to make decisions because of Title IX and then fight for funding,” Herman said. Mabry was well-suited for the challenge because she was “very principled,” Herman added. “She had very, very strong beliefs and was willing to fight for them.”

The first scholarship

McKinzie-Lechault ’79, right, was a prolific scorer for the Redbird basketball team who became the first woman to receive an athletics scholarship at Illinois State following the passage of Title IX.

Pat McKinzie-Lechault ’79—a prolific scorer on the Redbird women’s basketball team—became Illinois State’s first female student-athlete to earn an athletics scholarship. She remembers being called into Hutchison’s office in 1978.

“Coach said they had some good news, and they were going to award me this scholarship,” McKinzie-Lechault recalled. “I was really happy because I wouldn’t have to work a job that summer. I could work on my game.”

McKinzie-Lechault kept the news confidential because she worried the scholarship would distinguish her from teammates. She did, however, use it as personal motivation. “I looked at it as ‘I’m going to pay back the school for this honor by working on my game.’ And that’s what I did,” she said. “I started working out six to eight hours a day.”

McKinzie-Lechault finished her Redbird career with nearly 1,500 points and upon graduation, became one of the first women to play professional basketball in the U.S. for the short-lived Women’s Professional Basketball League (WPBL). Her team, the Washington Metros, folded a month after launching in 1979. She moved to Europe where she played professionally before becoming a coach, teacher, writer, and mother of two children—including a daughter who played college basketball and is now a pediatrician.

“Title IX opened doors to places I didn’t even know existed,” McKinzie-Lechault said.

“Young women today grew up with structured opportunities to play sports, to gain all of those values that we cherish that allow us to go into our lives and careers and use those experiences to truly be able to make a difference.”

Dr. Linda Herman

NCAA era

During the 1980s, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) fought to take control of women’s sports from the AIAW. Mabry credited the NCAA with doing a “good job” of giving female student-athletes better opportunities due to its ability to garner national sponsors for tournaments. Mabry, who retired from Illinois State in 1980, also said the demise of the AIAW led to fewer women in leadership positions at department and national levels.

Hutchison became interim director of Athletics from 1980 to 1982 and oversaw the merger of men’s and women’s programs into one department in 1981. Herman was then named Illinois State’s senior associate director of Athletics and senior women’s administrator in 1982 following a seven-year, hall of fame career as the head volleyball coach.

“I saw being in administration as an opportunity to make changes and be able to do it in a different way than just one coach could,” said Herman, who also served as interim director of Athletics on four different occasions. “I wanted to be a difference maker.”

Herman was tasked with guiding Illinois State through significant challenges such as dropping sports due to financial constraints and, in some cases, Title IX compliance. She also provided leadership as women’s athletics moved from the Gateway Collegiate Athletic Conference to the Missouri Valley Conference with their male counterparts in 1992.

“Linda became so knowledgeable and so qualified,” Hutchison said. “She got on lots of committees, and she fought the fight. She made sure that the women got as much of their share as they could.”

Throughout two decades in administration, Herman championed for equitable resources and opportunities that she sees women benefiting from beyond the athletic playing field.

“The value of sport is the relationships, growing as a person, and developing life skills,” Herman said while considering the impact of Title IX. According to the Women’s Sports Foundation, before Title IX, one in 27 girls played sports. By 2016, that number had grown to two in five.

“Young women today grew up with structured opportunities to play sports, to gain all of those values that we cherish that allow us to go into our lives and careers and use those experiences to truly be able to make a difference,” Herman said.

The next generation

Current Redbird volleyball student-athlete Kendee Hilliard ’21 has experienced the value of sports firsthand. As president of Illinois State’s Student-Athlete Advisory Council, Hilliard is embracing the opportunity to empower fellow student-athletes through initiatives that address important issues on and off the court including social justice, mental health, and career development.

The continued advancement of women’s athletics—50 years after Title IX—is another priority for Hilliard, who is completing a graduate degree and aspires to become a college athletics director by age 33. Only about 15 percent of Division I athletics directors are women, but Hilliard expects that number to increase.

Volleyball student-athlete Kendee Hilliard ’21, left, and recent women’s soccer alumna Kate Del Fava ’20, right, are advocating for the continued growth of women’s athletics.

“I see myself as continuing the job that my mentors have done for women in athletics,” Hilliard said. She has been inspired through work as an intern with Leanna Bordner, Illinois State Athletics’ chief of staff, deputy director, and senior women’s administrator—a role Bordner has held since Herman’s retirement in 2002.

“I’m going to be super relentless in making sure that I’m breaking ceilings as well,” Hilliard continued. “One of my favorite sayings is ‘Never be stagnant because we have goals to reach.’ Providing an opportunity for the next generation is key.”

Recent Illinois State soccer alumna Kate Del Fava ’20 is breaking glass ceilings at the professional sports level after becoming the highest drafted Missouri Valley Conference women’s soccer player ever.

A starting defender for the Kansas City Current, Del Fava and her teammates were involved through their players’ association in negotiating for their first-ever collective bargaining agreement with the National Women’s Soccer League. Approved in February, the agreement includes a nearly 60 percent increase in players’ minimum salary, annual raises, and increased benefits.

“It’s been a fight for women in all generations in this country to just be seen as equal and be seen as deserving of equal,” Del Fava said. “We’ve come a long way, but I still think there’s a long way to go.”

Celebrating Title IX

Echoing Del Fava’s sentiment, Herman is eager to celebrate Illinois State’s “great history and heritage” while “inspiring the future” during a three-day Title IX 50th anniversary event hosted on campus June 24-26. They believe the next 50 years need to see increased resources and national media exposure for NCAA women’s athletics along with greater representation and equitable pay in leadership.

Herman and Hutchison are hopeful that the current generation of athletes, including Hilliard and Del Fava, will write a new chapter in the unfinished narrative of women’s sports. “We want to educate and engage our current student-athletes,” Herman said. “They can be true catalysts of change.”

For more information about Illinois State’s Title IX celebration June 24-26, visit GoRedbirds.com/TitleIX.