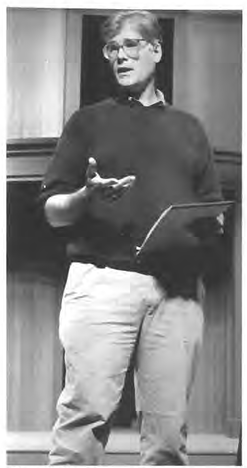

Festival Dramaturg Kee-Yoon Nahm spoke with director Doug Finlayson about the upcoming production of The Comedy of Errors at the Illinois Shakespeare Festival (ISF). This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kee-Yoon Nahm (KN): Before we dive into The Comedy of Errors, would you talk about your history with the Illinois Shakespeare Festival? You have directed here quite a lot over the years.

Doug Finlayson (DF): Cal Pritner, the founding artistic director of ISF, hired me to come direct The Merry Wives of Windsor in 1989. I was working in Chicago at the time after I had graduated from school. That was my first show at ISF and, really, the first time I directed Shakespeare. It was great because Merry Wives is a great play to start with if you do not have a lot of Shakespeare under your belt. I had a fantastic Falstaff in Michael McAlister, who was only 28 or 29 years—a nimble young man—but looked exactly like how you would imagine Falstaff to look. This was back on the old tennis court at Ewing Manor before they built the new theatre; it was just a stadium built around a tennis court. I came back in 1993 when the next artistic director, John Sipes, and I talked about the possibility of using American Sign Language in a show. So, I directed Pericles with Peter Cook in the title role—a deaf actor from Chicago. By the way, that was my first encounter with John Stark, who was my set designer. Then I came back in 1997 to direct Hamlet under Cal MacLean’s artistic directorship, and Romeo and Juliet in 2011 under Deb Alley.

KN: That is a lot of history! Of course, some of our readers might also remember that you were supposed to direct One Man, Two Guv’nors in 2020 before the season was cancelled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. If we count The Comedy of Errors, you will have directed five different Shakespeare plays at ISF under five different artistic directors. Even though One Man, Two Guv’nors never happened, I would like to touch briefly on the play since it also has a lot of physical comedy and doubling. That play is an adaptation of Carlo Goldoni’s The Servant of Two Masters, which is rooted in the Italian theatre tradition of commedia dell’arte. You could say that it shares the same DNA with The Comedy of Errors in that both are rooted in the stock character types of Roman comedy. Are you drawn to this kind of comedy?

DF: I love plays with physical comedy. But more than that, I love the idea of characters who truly believe in the problem that they have. In other words, the actors are not winking at the audience, as if they are saying, “Oh, look how funny we are!” It is the problem itself that can make something really funny, and I like that about the characters in The Comedy of Errors. Antipholus of Ephesus has no idea why people are telling him that he said or did things he did not do, as he is not aware that his identical twin has arrived in town. He has an irritable personality to begin with, but then the problems just keep piling on. Antipholus of Syracuse, meanwhile, feels that something is up. Beautiful women are talking to him. He is being taken out to dinner. His experience is equally unsettling, even if good things are happening. In other words, it is funny because the characters are just trying to live their daily lives, but that sense of normalcy keeps getting disrupted. From the actor’s perspective, this is as serious as doing Hamlet. It is just that the circumstances are such that we are able to laugh at it from the outside.

KN: Would you help our readers understand the style of comedy that you will be working with? Are there any cultural touchstones, like films or TV shows, that will help the audience imagine the humor?

DF: I love actors who are very broad in their comedic skills but are also completely believable. I have been cycling through the sitcom Third Rock from the Sun, and I really enjoy how Kristen Johnson, John Lithgow, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, and French Stewart play aliens who have landed in Ohio and are trying to pretend they are humans. Lithgow, who I think is a tremendous actor, is very good at this kind of comedy. He can do the most ridiculous things in an episode, but the fact that he was playing it like he is in King Lear really makes it funny. The actors commit to the story. And so, once the audience buys into the show, you can go anywhere. I see the same thing in Frasier. If you set up the rules as such, and the actors act like it is a life and death situation—it makes me laugh uncontrollably. You have to give the audience the vocabulary for watching it. That is what I am thinking about right now.

KN: That is interesting. You are not just laughing at characters because they are falling over and such, but because it is satisfying to see someone push ahead and try to achieve their goals, even if they are ridiculous. You root for them even despite the absurdity.

“The actors commit to the story. And so, once the audience buys into the show, you can go anywhere.”

DF: Yes, it is not about banana peels and prat falls. That kind of humor does not really speak to me. I love the fact that people are striving to do something.

KN: Since you mentioned the twins, I want to ask you about how you are approaching that. Shakespeare wrote two sets of identical twins in The Comedy of Errors: Antipholus of Syracuse and Antipholus of Ephesus are the masters, and then there are twin servants, both named Dromio, who work under each brother. Talk about absurd! Most productions try to cast similar-looking actors to play the twins and give them near-identical costumes, because the other characters have to keep mistaking one for the other. But you plan to have one actor play both twin brothers, right? So, one actor for the Antipholuses and one actor for the Dromios. Would you tell me more about that decision?

DF: Well, I was reluctant to do it at first. There are some staging problems you have to solve. You have to bring in a double for Dromio of Syracuse at one point, because both Dromios are in different parts of the stage at the same time. But for the most part, they are not onstage at the same time, so it can be done. In terms of costumes, I was talking to Brandon McWilliams, my costume designer, and I asked, “You know, since it is the same actor playing both twins, why would they have to be dressed the same?” Now, we are not trying to fool the audience. We want the audience to recognize it is the same actor. But it seems hilarious to me that Dromio of Syracuse would leave the stage and Dromio of Ephesus enters wearing a completely different outfit. Antipholus thinks this is a little strange, but he assumes that he is still talking to the same person.

KN: That creates an interesting possibility to explore each twin’s character separately, rather than treat them as mirror images. The two Antipholuses can become more individualized, with their own unique tastes in clothing, because we do not have to try to make two actors look the same. In a strange paradox, you are able to explore them as two different people because they are both being played by the same actor.

DF: And the two brothers are very different. I think of the Syracuse duo as adventurers. They have been sailing around the Mediterranean looking for their family members. Antipholus of Ephesus, on the other hand, has been living in town in his finery. He has money and does not get dirt under his fingernails. Antipholus of Syracuse seems optimistic throughout the play, whereas Antipholus of Ephesus is living the wealthy man’s life yet seems unhappy and ornery. That is a fun thing for an actor—you get to be both of these characters. It is going to be a challenge to make them feel different. But that gets me excited. The Comedy of Errors is not a play known for its depth. People do not go to see the play to witness thoughtful, deep considerations that a play like Hamlet would have. But that does not mean that the characters cannot have some depth. I tell my students that all the time: Who are these people when they are not in the scene? Who are these people when they are living their lives somewhere else? Where has Antipholus of Syracuse been before he arrives in Ephesus? What does their map look like? It would be interesting to explore that in rehearsals.

KN: Speaking of the setting, can you share anything about your discussions with the designers? There are so many directions that you can take with this play’s setting. Shakespeare’s version of Ephesus is inspired by classical and early Christian references to the ancient Greek city in modern-day Turkey, but he also takes plenty of liberties with the actual history.

DF: The historical Ephesus was a significant trading port in the ancient world. We are thinking of setting the play in this geographical region but changing the time period to somewhere between the tenth and twelfth centuries, during the late-Byzantine era. Ephesus is a significant port with merchants coming in from all over. The overriding feel is that of a bazaar or market because most of the play takes place in public spaces. In the opening scene, I want to create a sense of color and vibrancy to the world that Antipholus and Dromio of Syracuse enter into.

KN: Right. It is the equivalent of the big city where you can become lost easily if you do not know the streets—not unlike London. If you are trying to find someone, it makes sense that you would go to a place where many people gather. The big city also grants a sense of anonymity, where you do not know all of your neighbors. That makes it plausible for the abbess to live in Ephesus for years without realizing that her long-lost son has been living in the same city this entire time.

“People do not go to see the play to witness thoughtful, deep considerations that a play like Hamlet would have. But that does not mean that the characters cannot have some depth.”

DF: That to me is a good point. I have read about parallels between Ephesus in this play and London during Shakespeare’s life. I do not know how much knowledge Shakespeare had of the actual Ephesus. I imagine that audiences in Shakespeare’s time would recognize the bustle described in the play as their own urban environment. Shakespeare is all about anachronisms, and I think that is fun. We are creating our own world.

KN: I am excited to experience that world full of energy and laughter—although the characters will treat it seriously—when The Comedy of Errors opens this summer. Thank you for this early sneak peek into the production!