In 2007, Jan Dennis ’77 was in his dream job. He had left The Pantagraph in Bloomington after 24 years to become the Peoria bureau chief for The Associated Press, one of the oldest and most respected news organizations in the world.

He left behind his managing editor post, where he was starting to have to lay off longtime colleagues because of the paper’s declining fortunes. He also no longer had to write or edit run-of-the-mill stories that bog down a newsman.

“At AP I used to joke that the standard whether it was news or not is that it has to be equal to a 747 hitting a busload of nuns. Then it’s news,” Dennis said. “I was incredibly happy at the AP. That’s a career highlight for me.”

But after only five years, Dennis left for what many in the news business consider an escape hatch: public relations.

“I saw the clouds building in the industry,” said Dennis, who is in media relations at the University of Illinois. “In the AP, the Peoria bureau wasn’t New York City or Jerusalem, so if times had gotten bad, that would have been one of the first places they would have looked to cut. It speaks volumes that after I left, they never filled it.”

In the last two decades, hundreds of newspapers across the United States have closed, newspaper jobs have been shed, and readers have disappeared. Denver and Albuquerque lost two Pulitzer Prize-winning daily newspapers that had been in business for a combined 236 years. New Orleans’ main daily, The Times-Picayune, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 2006 for its coverage of Hurricane Katrina, was reduced to printing three times a week last year.

Entire newspaper companies, like the Tribune Co., have filed for bankruptcy. Other news chains cut thousands of jobs, skimped on supplies, chopped journalists’ salaries, ushered in unpaid furloughs, slimmed down print editions, and closed papers while giving executives lucrative bonuses and attempting to pay off debt incurred to buy newspapers the chains ended up gutting.

There are many causes for newspapers’ struggles. Most are blamed on a decline in advertising and classified ad revenue, especially since the Internet’s emergence, and a decades-long fall in circulation. The crisis has led to talk of government intervention and to the proliferation of nonprofit news organizations.

Newspapers’ free fall has made it hard for even the most idealistic reporters—those public watchdogs of democracy—to keep their heads up. In April, CareerCast.com ranked newspaper reporter as the worst job of 2013 with the combined worst environment, lowest pay, most stress, and bleakest outlook. A month earlier, Kiplinger listed journalist as one of the worst jobs of the future, urging reporters to find work in public relations. The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that in this decade, reporter jobs will decline by 8 percent.

“If we lose our watchdogs in the Bloomingtons in the world, that’s bad for people,” Dennis said. “You don’t just need watchdogs in Washington. The decisions that a city council or a school board makes are far more direct on people’s lives than what the Obama administration is doing.”

Inside the industry

In light of this newspocalypse, a couple of questions beg asking: Why does Illinois State University still teach print journalism, an industry that may share the future of the pony express? And if Illinois State’s journalism program is going to continue, what is it doing to adapt to this changing news world?

Such questions are not academic for Chris Grimm ’96, a copy editor and graphic designer at the GateHouse Media-owned Peoria Journal Star.

“What is the future of journalism?” Grimm asked. “Is it the Web? I think it can be a component. Right now revenue is the problem with that. Is it paper? You can make an argument the paper is still going to be relevant because that is where the majority of the money is still being made. Or—this is where I tend to lean—is it somewhere in between? Is it something like the tablet? I’m a big fan of the iPad and that aspect of journalism. And I think that is where we are probably going to end up. The problem is nobody knows. But eventually something’s going to happen.”

It’s a warning he issues to students at Bradley University, where he teaches journalism part time.

“It’s not my job to tell you, ‘Don’t do this.’ I do believe it is my job to tell you to have a backup plan. If you are headstrong and this is really what you want to do, then you need to be well-rounded. You need to be able to write, edit, design, shoot photos, and shoot videos.”

Versatility has indeed become a survival skill for journalists. Since 2007, GateHouse Media has cut the Journal Star’s newsroom staffing in half, Grimm estimated. It’s not that newspapers like the Journal Star aren’t making money. It’s that many newspapers are not making as much money as they used to, and not enough to make stockholders happy or to pay off debt.

Grimm might not be in the business long enough to see what’s next. GateHouse Media has adopted a cost-cutting measure that has become common. It is consolidating copydesks into central locations, called design hubs or houses, where multiple newspapers in the chain are laid out and edited. Next year, plans call for the Journal Star’s design responsibilities to be transferred to a hub. One in Rockford already designs GateHouse Media’s other Midwest papers. Grimm doesn’t think he will go to another newspaper if he loses his job because of the switch.

“This is what wears you down,” Grimm said. “I have gone through the downsizing of one newspaper; I don’t want to go through it again.”

Neither did John Plevka. He left the Peoria Journal Star, where he was managing editor, to become the general manager of The Vidette in 2012. Illinois State’s 125-year-old student-run newspaper is where alums like Grimm gained the type of real-world experiences that allowed them to seamlessly enter the news business. Plevka is not oblivious to the irony: He is training students to enter a field he just fled.

“I try to preach the message that storytelling still matters,” he said.

The Vidette has been forging ahead on the online and social media fronts since Plevka arrived. In January, The Vidette launched a smartphone application, and reporters have been integrating Twitter. The paper also hired its first full-time Web editor to beef up its website with photo galleries, video, and online supplements to the print edition, said Grace Johnson, a senior English major who was The Vidette’s editor-in-chief last school year.

“What I like here, versus at the Journal Star, is we will figure this out,” Plevka said. “We will succeed or fail, or somewhere in between. The Vidette will decide. Local thinking, local strategizing, in Peoria on those questions was out of the question. It was all preordained. It was just cut, cut, cut your way through this thing. That’s not a key to any success.”

The changes come as The Vidette is having to make difficult decisions about its print publication due to declining ad revenue and a need to keep up with college students who prefer electronic media to the newspaper. In August, The Vidette cut its Friday print edition in order to save an estimated $40,000 annually, Plevka said. The paper, which is now printed Monday–Thursday, had been producing five editions a week since 1976.

Will The Vidette eventually stop printing the paper altogether?

“Potentially. I do think that will be a longer ways away. Going strictly Web, I don’t think will be for five to 10 years because we don’t have the ability to get people online. We get spikes of interest when there is a tragedy. Other than that we don’t get consistent numbers online,” Johnson said, but added that the smartphone app has been downloaded more than expected.

Johnson is worried she might not get a journalism job once she graduates, but thinks she could adjust to an electronic only world. Even now former print reporters are finding jobs as bloggers at online publications like the Huffington Post, Slate, and SB Nation, and as reporters for television and radio stations and their websites.

Other Redbirds have proved an ability to not only adapt but flourish in the business.

Kristen McQueary ’95, a member of the Chicago Tribune’s Editorial Board, has followed in the tradition of several Illinois State alums—Chicago Sun-Times Editor-in-Chief Jim Kirk ’90 and The New York Times congressional correspondent Carl Hulse ’76—in reaching the upper echelons of the newspaper business.

“There is no question that newspapers are just not hiring as many people. And it is a tough business. I have watched so many good reporters and writers do something else because the money is not great. It’s hard to raise a family. And it’s very disheartening to watch your colleagues get laid off,” McQueary said.

“The upside is that I don’t know too many journalists who don’t land on their feet doing something else because your skill set is so well-rounded: You can write, interview, research.”

Though she considers herself print-first, McQueary is not some curmudgeon sitting in a smoke-filled office banging out diatribes against politicians. She tweets, appears on public radio talk shows, and participates in talking-head round tables in a television studio inside the Tribune’s newsroom.

“I’m sort of the board big mouth,” she said. “I think it is important. The people who are following us on Twitter are the movers and shakers in government and politics who should be reading what we are writing.”

She advises universities to teach the basics while preparing students to do everything.

“The basics are all still there. You need to be credible; you need to be accurate. You need to be curious and creative,” McQueary said. “But nowadays—I don’t how much they are doing it in the Chicago Tribune newsroom but certainly in the newsroom I just came from—writing your own headlines, shooting video when needed, taking pictures when needed, writing cutlines. The paper I just left we actually kind of laid the page out that our stories were going to be on. There is a lot you need to know now that you didn’t when I was just running around with a pen and a notepad.”

McQueary started her career as a cub reporter for The Pantagraph before moving to the crime beat at the Peoria Star Journal. In 1999, she became a political columnist for the Southtown Star, whose newsroom was cut to about 10 employees from a staff of 40 in the dozen years she was at the Chicago newspaper.

In 2011, she was hired as the statehouse reporter for the Chicago News Cooperative. The News Cooperative was an attempt, mostly by former Chicago Tribune reporters and editors, to produce news using a nonprofit model. The staff produced news for a website and for a special section in The New York Times.

“They did really remarkable work,” she said, yet the News Cooperative folded after three years due to funding problems.

Illinois State’s response

So what does the man in charge of Illinois State University’s School of Communication think of print’s future? Will it last another 15 years?

“Fifteen years, yes,” Executive Director Larry Long said. “Beyond that, I’m not really sure.”

Illinois State’s journalism major is a relatively recent development, born in 2004 with the emergence of three sequences: news and editorial, broadcast, and visual communication. Before that, the University produced journalists who majored in mass communications or an unrelated field.

produced journalists who majored in mass communications or an unrelated field.

“It became very clear to us at the time we were doing the right thing, but all of a sudden we were behind again,” Long said.

Now the plan is to merge all three sequences into one in spring 2014 in order to train students in all different media. There are also plans in the works to have all the University’s media entities—TV10, The Vidette, and WZND and WGLT radio stations—collaborate in what is still a developing concept, a media convergence center.

“Business in the news industry has converged, and as technology has converged, our degree program has converged,” Long said.

He envisions, for example, WZND using audio and print product produced by The Vidette when a radio station reporter can’t be live at an event.

“This would allow each entity to maintain their identity but share and capitalize on the resources of all,” Long said.

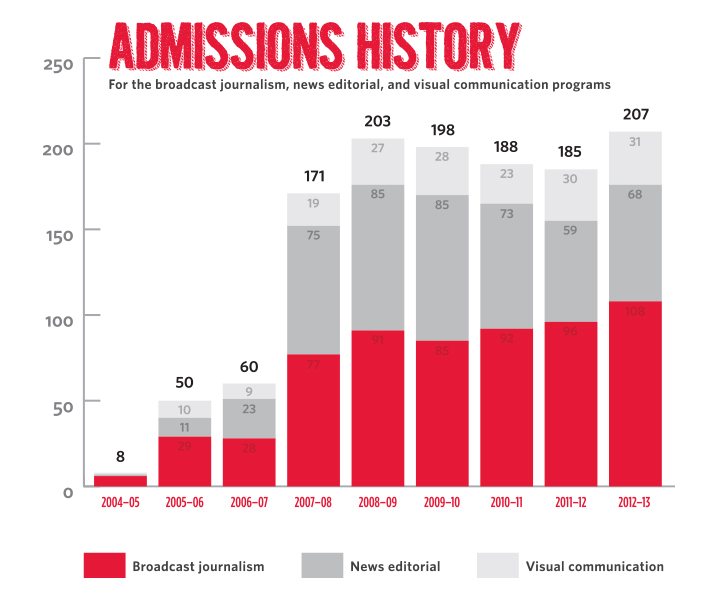

Perhaps a greater question is how the program can attract the best students into a field where quality jobs are tough to get. Despite the bad news in the news world, Long said the University’s journalism program’s enrollment is skyrocketing.

“There will always be news,” Long said. “People want to know what is going on in the world. But the way it is packaged is going to continually change.”

Andrew Steckling ’12 is betting his career on such optimism. Steckling entered the journalism program just as the economic and newspaper meltdowns reverberated across the country.

“It didn’t give me pause,” said Steckling, who served as news editor at The Vidette. “It gave my parents pause. Sophomore year of college was when a lot of these newspapers were shutting down. They were kind of like, ‘Uh-oh, he’s going to enter an industry that doesn’t exist.’ I know I won’t be making a lot of money, but I don’t care.”

Steckling has become the type of all-around journalist that the program is trying to develop. He learned design, editing, and how to write editorials, columns, and articles at The Vidette. He built on that with an internship at the Daily Herald in the Chicago suburbs, where he used social media, videography, and photography in his reporting.

“They called us mojos, mobile journalists,” he said. “You have to go out and pretty much produce the story from the field. You can’t sit behind a desk and make calls. You have to experience it.”

Steckling’s dream job is to become a movie critic. But for now he is in the trenches—one of six editors from the 14 during his time at The Vidette who have found work in the newspaper business.

He works at GateHouse Media’s design house in Rockford. But not for long. He learned during the spring that the design house will close in January to make way for a bigger hub in Austin, Texas. He has been guaranteed a job in the company, but he isn’t sure whether he will go.

Mapping the upheaval

The map below shows a sampling of closures, layoffs, and other changes at U.S. newspapers in 2013.