A fungus is among us – and providing hope.

Tom Hammond, an assistant professor of biology, is using Mother Nature’s own tricks to try and quell a harmful fungus.

For many of us, science experiments containing mold and other fungi were isolated to our third-grade classroom where we watched a piece of bread turn various shades of green and white.

Yet in his lab at Illinois State, Hammond is using fungi to learn the secrets of DNA, and battle genetic problems on the most basic level.

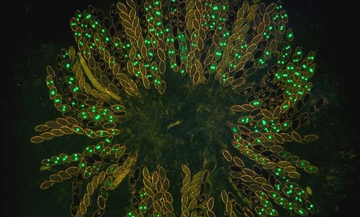

Working with the fungus Neurospora crassa, Hammond and his team study the organism’s natural genetic defenses. “Just like in humans, Neurospora has DNA chromosomes,” he said. “In some cases, these chromosomes can become selfish, and prevent other chromosomes from taking part in reproduction.” With support from government agencies such as the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Hammond hopes to learn how this process happens. This knowledge could then be used to target problem fungi here in Illinois.

“An example is an organism called Fusarium. If corn is found to have Fusarium, it cannot be sold because exposure to the organism’s natural toxins is dangerous – linked to cancer and birth defects,” said Hammond. “For the U.S., that means a huge economic loss of crops. But in developing nations that do not have the means to screen for toxins, it could mean sickness for people that eat the contaminated corn.”

In his studies, Hammond is trying to use naturally occurring DNA from selfish chromosomes that could block the toxins from developing. “Some Fusaria naturally do not produce toxins. We’re not sure why. If we can place selfish DNA into the right part of the genome, then that DNA could spread through the population of the fungus, significantly reducing its ability to form toxins.”

In his studies, Hammond is trying to use naturally occurring DNA from selfish chromosomes that could block the toxins from developing. “Some Fusaria naturally do not produce toxins. We’re not sure why. If we can place selfish DNA into the right part of the genome, then that DNA could spread through the population of the fungus, significantly reducing its ability to form toxins.”

This genetic approach would mean farmers could go without spreading fungicides, and Fusarium fungi would not need to be eliminated from agricultural areas. “If we can just tweak the parts of the genome that control mycotoxin production, then we can remove a threat and increase the safety of the food supply.”

The study is in the beginning stages, with Hammond’s students identifying and categorizing selfish chromosomes in Neurospora and Fusarium fungi. “It will be a long-term study, but with a long-term solution,” he said.

Hammond’s work has a strong legacy at Illinois State. Professor Emeritus Herman Brockman is a leading scholar in the field of DNA study through molds and fungi.

In fact, Hammond studied Brockman’s work in college, but did not make the Illinois State connection until he met Brockman at a dinner. “Everyone studies the Brockman and de Serres work in Neurospora,” said Hammond. “When I attended a dinner for Dr. Brockman, it finally clicked for me. One moment I thought, ‘Of course!’ and the next I thought, ‘I have some big shoes to fill.’”

Hammond can no longer duplicate the vats of mold Brockman once created for his studies. “The cost of some of the materials has jumped into the thousands of dollars now,” he said.

Yet Hammond is building on the work of Brockman, and taking DNA study into new directions.