A team of Illinois State University researchers received a nearly $300,000 grant from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) to continue work on a device aimed at helping investigators gather forensic evidence in the field.

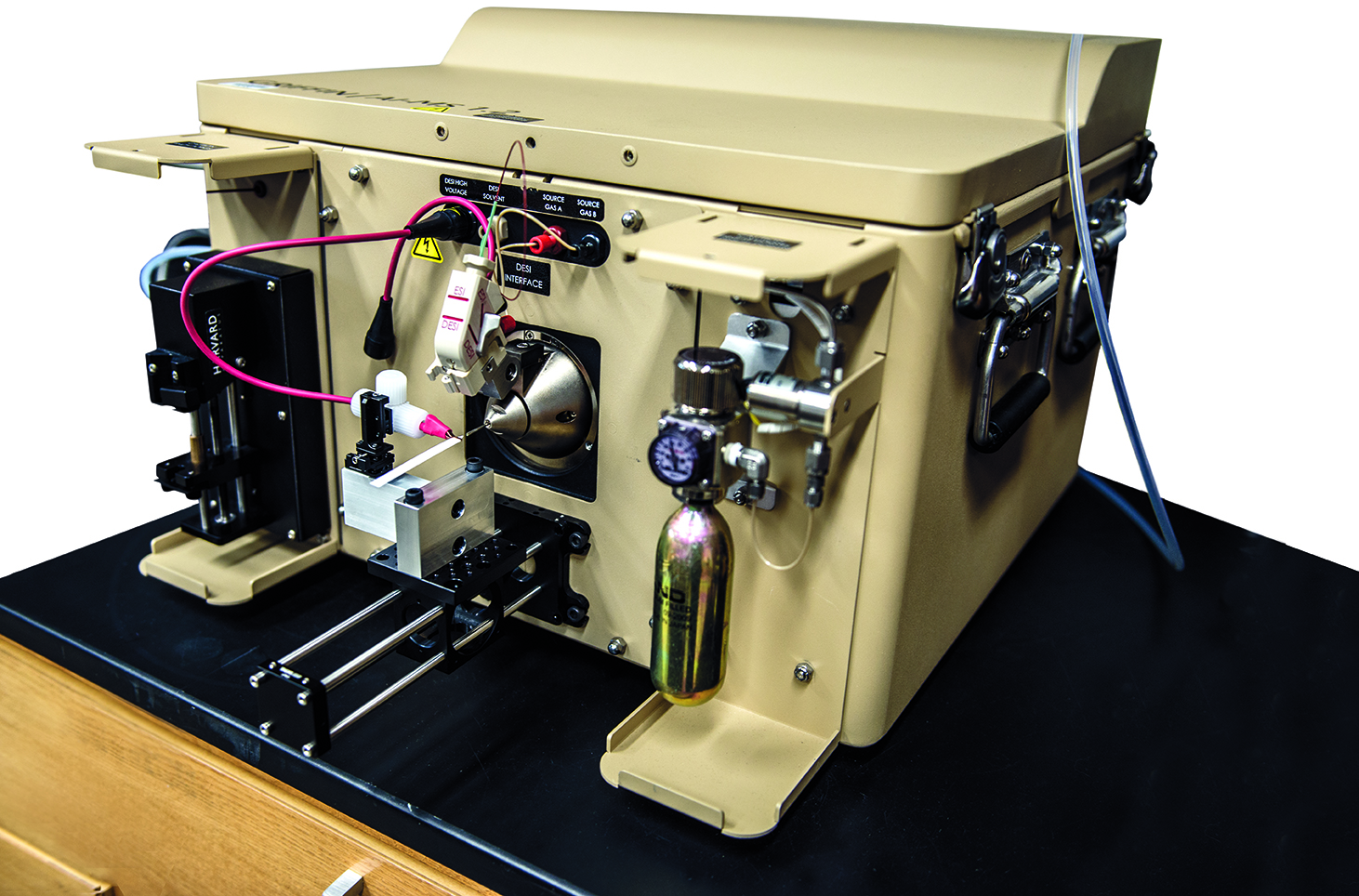

The grant, awarded to Department of Chemistry faculty members Jeremy Driskell, Jun-Hyun Kim, and Christopher Mulligan and Department of Management and Quantitative Methods faculty member Jamie Wieland, advances the development of a device called a portable mass spectrometer. About the size of a desktop printer, the portable mass spectrometer (MS) can analyze a substance onsite, making it useful for law enforcement to quickly examine samples of potentially illegal drugs at crime scenes. Originally created by FLIR Systems, Inc., the Illinois State team is adapting this device to work in the forensics realm.

“With all the new drugs coming into the illicit drug market, it’s becoming harder and harder for police to keep up with their current field test kits,” said Mulligan, who has been working on the device for the past six years. “Forensic labs are getting backed up to the point where it can take weeks to get results. This is a way investigators can get accurate answers on the scene.”

This is the third grant from the NIJ supporting the research behind augmenting the MS. The first grant examined whether the device could actually be adapted for forensic applications. The second was a cross-disciplinary effort with Mulligan, Wieland, and Michael Gizzi of the Department of Criminal Justice to assess if the device could provide legally admissible evidence and was cost effective for police departments. The latest grant helps the team take the next step in honing the device—incorporating a second tier of identification.

“A two-tiered test uses two different methodologies to examine the same substance,” said Mulligan. “This ensures there are checks and balances, and we hope this will yield court admissible evidence for police officers who would use the system under development.”

The device will incorporate a second test—Raman spectrometry—which is the expertise of Driskell. “Portable Raman systems are available and simple to operate, which makes them ideal for on-site analysis of drugs,” said Driskell, who will help to combine the Raman and MS systems in a single platform that can simultaneously analyze potentially illicit drugs. “While Raman and MS can each independently identify substances, confidence in this evidence increases if both methods give the same result.”

The team is also working to ensure that the instrument can examine bulk evidence (such as white powders) as well as trace residues of drugs. Kim has developed a methodology that can efficiently detect chemical compounds loaded onto paper-based materials with high-surface areas. He says the system will help “facilitate rapid analysis without purification steps and enhance differentiation of illegal substances with minimal false signals.”

Wieland will design controlled experiments to assess the accuracy of the device. “The goal of this project is to generate court-admissible results, entirely in the field, which hasn’t been done before,” she said. “Consequently, we need to produce extremely reliable results similar to those obtained in forensics labs.”

The team hopes a two-tiered device will be ready for deployment in the next five years.