In the following Q&A, curator Jessica Bingham and artist Eric Anthony Berdis talk about Berdis’ work and exhibition Don’t let them clip your tiny little insect wings, currently on view at University Galleries of Illinois State University through December 15. A satellite exhibition, Eric Anthony Berdis: remember you are a sunflower: drawings, artifacts, and scores for a performance, is on view through December 15 at Milner Library, on the sixth floor. All events are free and open to the public.

Jessica Bingham: Your installations and performances tend to be playful. Comical drawings, colorful sequences, and participatory performances all allude to the idea of play.

Eric Anthony Berdis: My installations are a world, an exploration through drawing and placement of objects. In this exhibition, there are figurative ghosts with their own personalities.

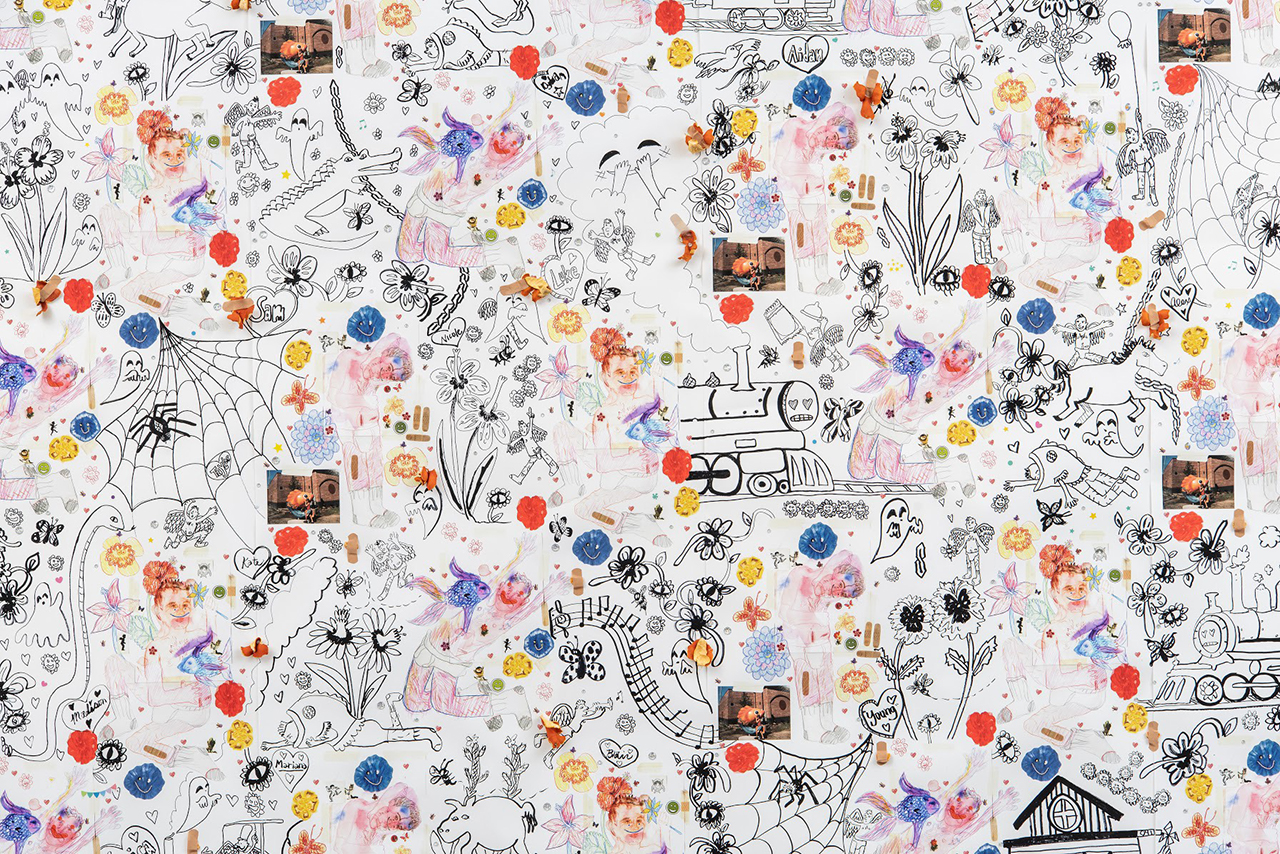

Their spatial distances create relationships—some together, some alone. The wallpaper drawing is a repeated motif that builds up to an immersive pattern of floral and figurative elements that play with the landscape. As you get closer, you see the activity happening as well, informing how one sees the sculptural work.

Nelson Goodman writes in Ways of Worldmaking, “We start, on any occasion, with some old version or world that we have on hand and that we are stuck with until we have the determination and skill to remake it into a new one.” My materials come from my experiences: old stained T-shirts, thrift store castoffs, and craft store treasures that made their way into my world. The materials are familiar, and some, through manipulation, become unrecognizable, queer in the separation from their previous life.

You draw connections to LGBTQ+ artists in some of your recent work, both living and deceased, including David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring, Zoe Leonard, Félix González-Torres, to name a few.

I started the research for this exhibition at University Galleries by looking at Félix González-Torres, in particular Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA). It is an allegorical representation of his partner, Ross Laycock, who died of an AIDS-related illness in 1991. Comprised of 175 pounds of candy, corresponding to Ross’ body weight, viewers are encouraged to take a piece from the pile. The diminishing amount parallels Ross’s weight loss and suffering. González-Torres stipulated that the pile must continuously be replenished, metaphorically granting perpetual life. This representation of a ghost is beautiful, poetic. It made me question how other queers would want to be represented.

In a similar vein you recently incorporated fresh oranges in an installation, which shriveled and diminished over time. The oranges were also an ode to Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit (for David). Is there a reason why you use faux flowers for this exhibition instead?

There are some logistical reasons for not incorporating oranges. Although I love bugs, I doubt the gallery wanted me to attract them. The wallpaper served as a backdrop for the ghost sculptures and the top was lined with orange peels that fell as they withered. They permeated the space with an aroma, and as the exhibition went on, the oranges continued to perform.

The work here is inspired by Allen Ginsberg’s poem “Sunflower Sutra.” In the poem, a sunflower is found growing from the railroad tracks, covered in soot and masquerading as a piece of machinery. The poem prompted me to be present and proud of who I am—I am standing on the shoulders of giants who fought for my right. Faux flowers have replaced the oranges to connect to this poem. It’s also exciting to see how they change the horizon line of the installation. It gives the audience a sense that they are six feet underground with flowers growing overhead; it transforms the gallery into my own world.

This exhibition also closely aligns with the tragic death of Matthew Shepard. Can you elaborate on that connection and the reoccurring ghost theme?

I position this work to celebrate life and death, and the impact people like Matthew Shepard had. Memories of past individuals are so complex. I challenge that we would adorn a uniform in the afterlife; I don’t think anyone’s ghost would be a white cotton bedsheet. The sculptural ghosts have two sides to them, an embellished underlayer and an afghan blanket cut to create a smile, which when draped, changes to a frown or scream. I am specifically imagining what a queer ghost would look like. This comes from examining the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, as well as altar spaces that are made after someone’s life is suddenly taken; improvisational and filled with personal items, mementos, and love notes.

Your childhood, particularly time spent with your dad and grandfather, have also informed your current work. Can you talk about those personal memories and how they impacted you?

It’s hard to deny my family’s influence on my work. I’m a twin and bring attention to that with a piece in this show. As for my father and grandfather, they both work in the automotive industry in Erie, Pennsylvania, as CNC machinists making parts for trains. A motivation for this work came from reflecting on the queer suicides that happened in my hometown, and the commonality of walking on the railroad tracks. The offensive phrase, “Go play on the railroad tracks,” was often said to me since I was an effeminate child who was trying to figure myself out. In “Sunflower Sutra,” Ginsberg writes: “Poor dead flower? when did you forget you were a flower? …You were never no locomotive, Sunflower, you were a sunflower!” Those poetics are fuel to keep making.

In many ways, your art is a means of educating others on the importance of safe, inclusive spaces and language. How do these conversations influence the outcome of your performances?

The performances change quickly, as they are naturally responding to the environment and my body. Like education helps us change and adapt, so do the spaces we occupy. My work happens in response, and often times I try to echo an experience. My life bounces around between being a teacher, artist, friend, brother, and queer person, and I try to tiptoe those lines in my identity to open up gaps in understanding.

I think it is important to note that you used to be an elementary school teacher. You now facilitate learning through your work. Quite honestly, it doesn’t seem like your work would exist so purposefully without the educational component.

Oh yeah, if you want to see some amazing performance art, come to Teacher Eric’s Kindergarten Classroom during indoor recess! All jokes aside, I didn’t experience a lot of art growing up. The first time I went to a museum was when I was studying art education in college. Now I intentionally consider a younger audience. My sloppy craftsmanship leads to a naive approach in making—it brings me joy to see a smile made of metal studs from Hot Topic. I love when children experience my work; they bring a very fresh perspective and teach me in the process.

With teaching as an integral part of your practice, I am curious about your new role at Virginia Commonwealth University as the LGBTQIA+ Service Coordinator. I’m sure the advice and information you provide students is incredibly valuable.

It feels completely empowering to be able to support young people in their identities and work with students in some of the most formative years of their life. I identify as a “late bloomer” in my queerness, so college was a formative time for me to work through my acceptance. It’s awesome and inspiring to be able to work with students along the spectrum of queerness and allow them to hone their leadership skills, as well as connect, laugh, and gossip about Euphoria, Pose, and Drag Races. I feel like all we did when I was in gay clubs was cry, so it’s nice to see the bright side of things!

An important contemporary topic that surrounds the LGBTQ+ community is how to address and respectfully acknowledge names and pronouns. This issue has been circulating university campuses, as well as home and work environments. How have you approached this?

“Hi, my name is Eric, my pronouns are he/him/his. Sometimes I feel more they/them/theirs. Either is fine.” “What is your name?” “What pronouns do you use?” These phrases are part of my everyday language, name tags, and emails. Sharing pronouns is a gift; it’s like coming out to someone every time you speak. I don’t expect everyone to share, but I do expect that everyone is treated with respect. I aim to inform folks who have a different opinion to see where I’m coming from.

You don’t tiptoe around this topic in your work at all. In fact, on the “About” page of your website, you hyperlinked this question: “Do you have questions about Eric’s pronouns?” I think that is fabulous! The link prompts visitors to “ask” your pronouns without having to be present to do so, leaving no room for uncertainty while promoting self-assertion.

I send a lot of emails, and often Eric Anthony Berdis gets shortened to Eric A. Berdis, which if you read it incorrectly is Erica…thanks, Mom! This has made for a lot of embarrassing emails. I often reply, “Lol, that was my nickname in grade school, it’s cool.” But for some queer people, they are reminding folks of their identity daily, hourly even. It weighs on the spirit, body, and mental health. So, if I’m able to subvert one person into learning about why I share my pronouns in my email, or even better, help them to consider sharing their pronouns on their email, that’s a success.

You begin almost every performance by introducing yourself with your name and pronouns, and then ask participants to do the same. That could be an uncomfortable experience for some. Has anyone ever refused to share?

I think normalizing pronoun sharing is important and I want everyone I encounter to feel valued and be referred to what feels best. Sharing my pronouns is a simple gesture that helps conversations and relationships. In my performances, I am often asking someone’s pronouns with a lot going on—I’m standing on one leg, in my underwear, riding a hobby horse. So, I understand when someone doesn’t comprehend our interaction 100 percent. Some folks might ignore the pronoun question, so I’ll repeat it. If they choose not to answer, I do my best to refer to that individual by their said name for the remainder of the interaction. If someone asks why to share their pronouns, I just try to explain the first part, “I want everyone I encounter to feel valued even when I’m not saying your name.”

You’re incredibly transparent and share your battle with body image. Your Instagram bio reads, “I’m an artist. I have all my teeth. Queer, and not sexy,” followed by “He/him.” Body confidence is something many people struggle with, so it’s refreshing to see you put those words out there with such bluntness.

None of my work is sexy, nothing about me is sexy. My craft is haphazard and heavy handed, my performances are uncomfortable, and I’m a little clumsy. The work is a counterargument to beefcake art and masculine ideals that are too often portrayed. Those works have importance, but I try to bring humor into everything I do. I try to live authentically. I am fortunate to be able to be an artist, as well as to work with queer communities as a vocation. I am truly thankful for the ghosts and passionate people who did this work before me. It’s an honor to take the baton and run on my own path.

University Galleries, a unit in the Wonsook Kim College of Fine Arts, is located at 11 Uptown Circle, Suite 103, at the corner of Beaufort and Broadway streets. Parking is available in the Uptown Station parking deck located directly above the University Galleries—the first hour is free, as well as any time after 5:01 p.m.

Please contact gallery@IllinoisState.edu or call (309) 438-5487 if you need to arrange an accommodation to participate in any events related to these exhibitions.

You can find University Galleries on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, and sign up to receive email updates through the newsletter.