Baseball players are so often judged by stat lines. How many home runs do they hit per year? What’s their fielding percentage?

But the personalities and stories behind those players have made the sport withstand the test of time, especially at the professional level, as proven by two Illinois State graduates who have had a powerful impact in their similar sport despite playing in entirely different eras.

Appears In

Nominate royalty for Homecoming 2020

Weed wizard: Professor alters plant genes to create wonder crop

Trust through truth: Alum tackles tough metro assignments by building relationships

Redbird legacy: Like father, like son

How we met: Mary and Phil Loveall

Pause for applause: Spring 2020

Thanks to you: Michael Jones ’92

High graduation rate tops national average

Lifelong learning: Alumni appreciate free access to webinars

Historic appointment: Alumna first African American and female to lead ISU’s governing board

Overcoming dark days: ISU’s response to national mental health crisis

Redbirds will face Sooners in 2023

Cubs choose former Redbird

Where are they now? Susan and Steven Kern

State funding released for renovation of Wonsook Kim College of Fine Arts facilities

Seven receive 2020 Alumni Awards

Dream come true: Redbird star Del Fava drafted by pro soccer league

At age 99, Betsy Jochum ’57 was a pioneer in a league that showcased women’s athleticism while the nation was at war. Paul DeJong ’15 is still writing the pages of his career as a 26-year-old Major League All-Star who is just as comfortable in a lab coat as he is a baseball uniform. Both have put their own stamp on the game that goes beyond the numbers on the back of their baseball cards.

Sliding into history

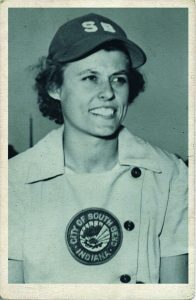

Betsy Jochum ’57 could see the appeal of the uniform.

The skirts that cut off just above the knees appeased the domestic role cast upon women during the time period. They also showed just enough bare leg to draw a certain intrigue.

For the players wearing them, it hurt to slide, carving up skin from their calves to thighs all in the name of making it to base safely. Jochum didn’t care. She welcomed the needed toughness.

Playing for the South Bend Blue Sox in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL)—made famous by the movie A League of Their Own—“Sockum” Jochum was a prototypical leadoff hitter who got on base any way she could. She’d then wreak havoc on the basepaths, often beating the throw by acquainting herself with the infield’s dirt surface.

Her play made her a fan favorite in a league created during the height of World War II to fill stadiums as Major Leaguers fought overseas. There were outside voices criticizing females challenging society’s status quo at the time. Women playing professional baseball made the noise louder.

Once again, Jochum didn’t care. Sports-obsessed since a child, she was getting paid to play a game she loved. To heck what naysayers thought. She was too busy eyeing up the base she was about to steal next.

“That’s just the background noise,” said Jochum, who still has plenty of energy to burn in her Indiana community of South Bend. “You don’t pay attention to that, really. People think you did, but you don’t. I didn’t, anyway.”

From Jochum’s perspective, the more scars on her legs the better. That meant she was piling up the hits and scoring runs for her team, becoming one of the league’s toughest outs during her five-year playing career from 1943-1948. In 1944, she led the AAGPBL in batting average (.296), hits (128), and singles (120). She stole 127 bases and also pitched in her final season.

The league’s popularity spiked 50 years after its existence with the release of the Hollywood film. Jochum doesn’t recall anybody saying there’s no crying in baseball, a popular line from the movie, but has many proud memories of her part in a league that put a spotlight on women’s athletics.

“They made history because they played a professional sport,” said Marilyn Thompson, director of marketing at The History Museum in South Bend. It has a gallery dedicated to the AAGPBL. The league is showcased as well in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., which is where Jochum’s uniform is displayed.

Sports always drove Jochum. The daughter of German-speaking Hungarian immigrants grew up in blue-collar Cincinnati during the Great Depression. She and her brother played whatever they could on the pavement. Soccer, horseshoes, tennis—you name it. She started softball around age 12, with skills that landed her on a travel team across the Ohio River in Kentucky. She played in a pair of national tournaments.

In early 1943, she came across a newspaper ad. The AAGPBL, newly formed under the direction of Cubs’ owner Philip Wrigley, was holding tryouts for women seeking to play professional baseball. Jochum didn’t need to read much else. Before long, she was headed to Wrigley Field in Chicago for a tryout, stepping onto grass that was mostly gender exclusive.

“It was awesome,” she said. “Women don’t go on Wrigley Field very often.”

She made the diamond her home for five years, traveling by bus and train across the Midwest to play ball until retiring at age 27. She had asked the Blue Sox for a raise. They instead traded her to Peoria, but she didn’t want to leave South Bend or her team. It was time to pursue other options, so she left the league that disbanded in 1954.

She still loved sports and hoped to teach physical education. Twila Shively ’54, who played five seasons on three different AAGPBL teams, told Jochum about a school known for its education about three hours away from South Bend. Jochum consequently came to Normal and obtained her teaching degree.

“You didn’t have to buy your books there,” she said of Illinois State. “That was a big factor.” She remembers the University having a small-campus feel back then. She worked as much as she could in administrative offices between classes, leaving little time for campus activities. There was no option for her to continue as an athlete given Illinois State did not field a varsity softball team until 1965.

Jochum’s degree in health, physical education and recreation prepared her to teach physical education. She did so for 26 years, mostly in the South Bend district at Muessel Elementary. She also embraced her role as an ambassador for the history of the AAGPBL, keeping the spirit of the league alive by telling her story across the country and encouraging female athletes to pursue their dreams.

At the time Jochum played, she wasn’t thinking of the effect she might have on future generations. And yet she made history playing professionally well before the Title IX-era. She now delights in watching women compete on television, from her local Notre Dame basketball players to the U.S. women’s soccer team in the World Cup last July.

While such high-caliber play is taken for granted today as common, Jochum can testify to how gradual progress has been for female athletes, including herself. While sliding bare-legged into bases back in the 40s, Jochum and her league mates laid a foundation for women in sports.

It all adds up

In his present life, Paul DeJong’s work usually warrants an exclamation point. He blasts titanic home runs in front of 40,000 people. He dazzles in the field with diving plays and laser-beam throws. But the St. Louis Cardinals’ shortstop has always been motivated by a different form of punctuation: The question mark.

The 2015 biochemistry graduate has sought answers on how the world works around him since he can remember. He understands there’s a process involved with almost everything. As he put it, numbers are a language to describe science.

“I’m definitely more of a big-picture guy,” DeJong said.

Perhaps that mindset has contributed to his rapid rise to baseball stardom, going from under-recruited high school prospect to Major League All-Star. DeJong has squeezed the most out of every stop in his journey because he loves to learn. He believes in experimentation and seeks out scientific reasoning.

At Antioch High School, he was named the science department’s “most outstanding student” and earned a spot on the National Honor Roll. He one day hoped to go to medical school. Because of his academic prowess, DeJong had his pick of universities.

He also believed he was good enough to play ball at the next level. DeJong was an all-area player in high school, hitting .430 as a senior. But he tore his ACL twice in basketball, causing him to miss a pair of seasons and fly under the radar of high-profile baseball schools and scouts.

DeJong wanted to excel athletically and academically. Illinois State offered opportunity on the field and in the classroom. He signed on to be a Redbird as a preferred walk-on and came to campus as another student-athlete. He left as one of the best ever.

“He is my mental image of a student-athlete. Somebody who is athletic, who works to develop those skills, but also pays attention to the academics.” – Dr. Marjorie Jones, biochemistry professor

“It was all for the better, and when it counted, Illinois State was there,” DeJong said. “It’s all part of my journey now, so I never have any mixed feelings about it. It’s all just what my story is.”

DeJong hit .326 with 23 home runs and 113 RBIs in 144 career games at ISU. He was twice named first-team All-Missouri Valley Conference, while twice getting drafted by a Major League team. When the Pittsburgh Pirates selected him in the 2014 draft, DeJong had already made up his mind he was going to remain at ISU and complete his degree. Doing so meant another school year to frequent favorite eateries such as Flat Top, D.P. Dough, and La Bamba Burritos.

He finished with a cumulative 3.76 GPA and crossed the commencement stage one month before the Cardinals took him in the fourth round of the 2015 draft. That same year, he earned the Missouri Valley Conference Commissioner’s Academic Excellence Award.

“He is my mental image of a student-athlete,” said Dr. Marjorie Jones, a biochemistry professor. “Somebody who is athletic, who works to develop those skills, but also pays attention to the academics. It was obvious he was very serious.”

Jones had DeJong as a student at the same time scouts began flooding Illinois State baseball games to see the power-hitting right-hander. Despite the rigorous baseball schedule, the two often conversed in detail about a subject matter. Jones recalled a particular conversation on athlete nutrition.

“We were talking about how best to prepare spinach. Should you eat it raw? Should you fry it? We had this great discussion,” said Jones, who wouldn’t be surprised to see DeJong pursue medical school once his baseball career is over. “It’s fun as faculty to have students actually care about learning and then use what they learn.”

That kind of attention to detail has paid dividends in DeJong’s professional baseball career. Never ranked as a top-10 prospect in the Cardinals’ system, he shot through the minor leagues and made it to St. Louis in just two seasons. The big picture was always in mind. He got there by doing all of the little things, such as preparing his body with most effective nutrients correctly.

Last season, he played in 159 of 162 regular season games and started all nine postseason contests for the National League Central Champion Cardinals. It was DeJong’s first go around in the playoffs. He went 2-for-4 with two RBIs during St. Louis’ 13-1 Division Series clinching victory against the Atlanta Braves on October 9.

“Everything was just about the now,” DeJong said of the playoffs. “It really made the game feel a lot more open and a lot more engaging.”

Entering 2020, DeJong had slugged 74 home runs in 382 career Major League games. He was a finalist for the National League Gold Glove award last year. The Cardinals rewarded him with a six-year contract extension in March 2018. He played in his first All-Star Game last July—not too far removed from his days suiting up on spring afternoons at Duffy Bass Field and experimenting in a campus laboratory.

If being a Major League All-Star is the science, the steps in the journey are the numbers to describe it. DeJong remembers each one with gratitude, especially his growth at Illinois State. “It really makes me appreciate that it’s almost an out-of-body experience knowing where I came from,” he said. “I try to be humble with the journey, and that’s why I love getting back to ISU whenever I can.”