The Winter’s Tale contains many memorable elements that make it unique among Shakespeare’s plays: an oracle that proves a character’s innocence, a sheepshearing festival, and, of course, Hermione’s statue that comes to life. It also has wonderful monologues that actors often use in auditions. But the most famous line in the play is perhaps a little stage direction in the third act. You may have heard it, even if you are not familiar with the play.

Let me set the scene first. In the previous scene, King Leontes ordered that his newborn daughter must be banished into the wilderness, believing that she is the bastard child of his childhood friend, King Polixenes of Bohemia. This deed falls on Antigonus, a lord in Leontes’ court, who sails to the foreign land with the baby. But right after Antigonus laments the poor child’s fate, Shakespeare inserts a stage direction that certainly raises some eyebrows:

Exit pursued by a bear.

Shakespeare has Antigonus run offstage followed by a wild bear that appears out of the blue. A moment later, we hear from the Old Shepherd’s son about Antigonus’ horrible demise in gruesome detail:

“to see how the bear tore out his shoulder-bone, how he cried to me for help, and said his name was Antigonus, a nobleman. […] and how the poor gentleman roared and the bear mocked him, both roaring louder than the sea or weather.” (Act 3, Scene 3)

And so, we witness the final casualty of Leontes’ blind rage. Thankfully, the shepherds save and adopt the abandoned baby. The kind-hearted peasants also decide to bury Antigonus’ remains after the bear has finished its human meal.

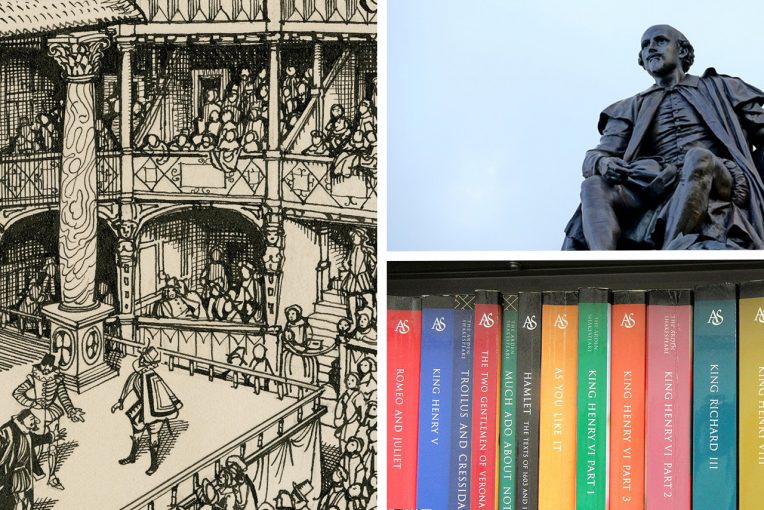

The stage direction raises questions for scholars and artists alike. What was Shakespeare thinking when he wrote this in the play? Unlike many other stage directions added by editors in modern publications, this stage direction actually appears in the earliest surviving text: the First Folio of 1623. Did Shakespeare actually want Antigonus to be physically chased by an actor playing a bear or a live animal? Was it an offstage sound effect? Was it expressed symbolically? There is no way to know for sure. But it is fun to imagine the possibilities.

(The Bodleian First Folio digital facsimile, University of Oxford)

Interestingly, we have a spectator’s account of the The Winter’s Tale at the Globe Theatre in Shakespeare’s day. The astrologer Simon Foreman kept brief notes of some performances he saw in 1610 and 1611. His notes mention the major plot points, including the setting of the two kingdoms, Leontes’ jealousy, and Perdita’s upbringing among shepherds. But no mention of the bear. Does it mean that the moment was cut in performance? Or did the bear chase fail to impress Foreman?

Some historians believe that an actual bear may have appeared in this scene. Many of the London theatres at the time were close to bear-baiting arenas, a popular form of live entertainment. In bear-baiting, a chained bear (or horse or lion or other large animal) was attacked and sometimes killed by hunting dogs—an upsetting custom that could be compared to dogfights and other kinds of animal abuse today. This means that there may have been a supply of bears—both wild and trained—that a theatre company like the King’s Men could access. Furthermore, while the stage direction can feel random to us, Shakespeare’s original audiences might have been used to seeing bears in shows. This could explain the omission in Foreman’s notes.

Shakespeare directly references bear-baiting in some of his plays. A well-known example is Macbeth’s line: “They have tied me to a stake. I cannot fly, / But, bear-like, I must fight the course” (Act 5, Scene 7). Much like those tortured bears, Macbeth feels the binds of fate but must fight for his life until the bitter end. In the context of Macbeth’s tragedy, Shakespeare seems to be cognizant of the cruelty in trapping and torturing a bear for sport. Although there are not any lines that suggest sympathy for the wild bear in The Winter’s Tale, Antigonus hears hunting horns before his fatal encounter. This suggests that the bear itself is being chased when it sees a human being in front of it. Quite possibly, this scene is about the collision of two scared victims, each trying to escape death.

The bear was sometimes cut in later periods, trying to make Shakespeare’s play more plausible. But that seems to be a fool’s errand—the bear is but one of many moments in The Winter’s Tale that strain belief. Indeed, the play is about accepting things that are hard to buy. “It is required / You do awake your faith” (Act 5, Scene 3), as Paulina says when Leontes sees Hermione’s statue. Most productions today treat the bear stage direction as an opportunity for creativity, using theatrical magic to conjure the bear’s presence—imposing, terrifying, perhaps even a little pitiful. Or, a production may choose to embrace the absurdity of the bear’s surprise intrusion, using this moment to transition from tragedy to comedy. In any case, this infamous, five-word line has provoked endless discussion, demonstrating how even the smallest detail in Shakespeare can spark the imagination. How will the Illinois Shakespeare Festival (ISF) take on Shakespeare’s overbearing challenge? Find out this summer as ISF returns to live theatre. And rest assured that no bears will be harmed in our staging of The Winter’s Tale.