Festival Dramaturg Kee-Yoon Nahm spoke with director Lisa Gaye Dixon about the upcoming production of Much Ado about Nothing at the Illinois Shakespeare Festival (ISF). This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kee-Yoon Nahm (KN): Before we get into Much Ado about Nothing, I want to remind our readers that you were recently in a production of August Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago. Would you talk a little about that experience first?

Lisa Gaye Dixon (LD): Getting to work on a great script and a great role at an internationally renowned theater with some fantastic actors is already a plus. But it is also humbling as a teacher at a professional theater training program to practice what I preach to my students. It is refreshing to be just a student or an actor again. That fills you differently than teaching or directing does. I really enjoyed the process of learning again and discovering again. It gets my creative juices flowing in a different way.

KN: Congratulations on a wonderful production! Would you tell me about your history with the Illinois Shakespeare Festival?

LD: I was at Illinois State University as a graduate student in the mid-’90s. The student actors were not always used in the festival, so it was always a dream for us. I took two Shakespeare courses while I was at ISU and played Queen Margaret from Richard III in one of those classes. That is where I first discovered myself inside of Shakespeare. After graduating, I moved to London to do some work. When I came back from London in 1997, my old teacher Patrick O’Gara asked me to play Margaret in the 1999 ISF season. I also played Mistress Quickly in The Merry Wives of Windsor. It was a huge honor for me at the time. The majority of my career had been overseas, so this allowed me to get my toes back in the water here.

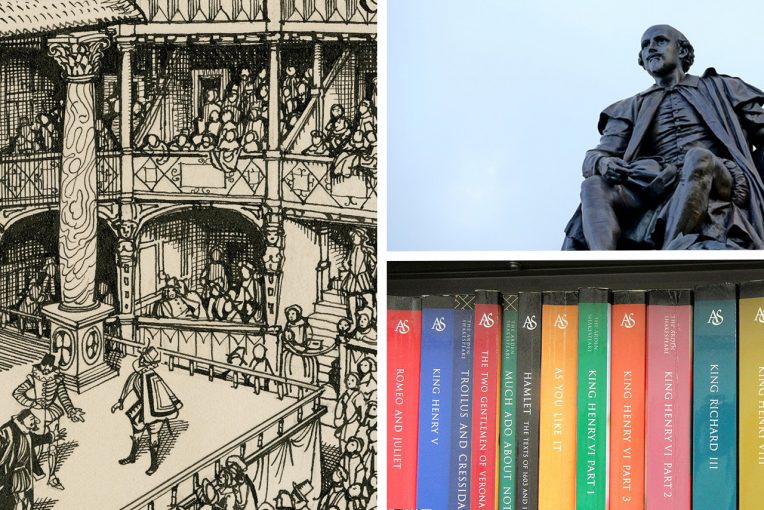

The next time I was at ISF was in 2003, where we did one of the most fun plays I have ever done and something I have considered directing myself: The Knight of the Burning Pestle by Francis Beaumont, a contemporary of Shakespeare. It was a very funny play directed by Bill Jenkins, who is directing The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (abridged) this season. I also played the tenant in King Lear and the goddess Hymen in As You Like It, singing the final song in the above.

After that, there was quite a hiatus. I came back in 2019 to be in As You Like It, Caesar, and Pride and Prejudice. And then last summer, in 2021, I played another dream role of mine—Paulina in The Winter’s Tale—as well as Escalus in Measure for Measure.

KN: You have been in almost every season since I started working at ISF, so I assumed you had a lot of history with the festival. But I am learning now that your heavy involvement with ISF has been a recent trend.

LD: Well, I think part of it is because of a change in the artistic direction. We are having new conversations about race and gender, and doing a lot more cross-gender casting than in the past. So, I could play roles like the Duke in As You Like It rather than just the traditional “pants roles.” In the past, I have played Stefano the drunken butler in The Tempest at Milwaukee Shakespeare and Eubulus in Damon and Pythias at the Globe, which were traditionally male roles. There is far more of that now, which gives more women a chance to be in these plays. At the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where I teach, we did an all-female version of Henry IV, Part 1, and I played Falstaff, which was so much fun. It was also wonderful to see women inhabiting roles like the Earl of Douglas or Prince Hal or the King.

KN: There are now many examples of cross-gender casting and all-female Shakespeare productions. It may have been a radical idea in the past, but it has settled into the broader theatre culture.

LD: Yes, and the same goes for transgender actors or actors of color. When I first started acting in Shakespeare, there were very few people of color that were in the cast with me, unless it was Othello or Aaron the Moor. The fact that I got to play Margaret when I first came back to the U.S. was a big deal, not just to me personally but also in terms of the theater culture. I love that we are expanding our ideas and that audiences are going along with it. For a long time, I would hear from artistic directors that we just cannot find a role for you, that we are not sure how to use you. Now, I hear less of that because they are widening the array of different ways in which they could use someone like me.

KN: Once those doors are opened, it is remarkable how quickly audiences can adjust. After the first 15 minutes of a show, people understand the conventions that the production is using.

LD: On one level, it is pretend even though we are holding a mirror up to ourselves. So, let us find the best people who can do the pretending no matter their gender or race or ethnicity. Once we do that, we have a great show. If that actor is good at what they are saying and doing, then you buy who they are. That is it.

KN: You are making your directorial debut at ISF after working for multiple summers as an actor. How did you come to choose Much Ado about Nothing?

“The fact that I got to play Margaret when I first came back to the U.S. was a big deal, not just to me personally but also in terms of the theater culture.”

LD: On the most basic level, Beatrice is one of my dream roles. But unless we are doing a version of the play where everyone in the company is a senior citizen, I feel I am a bit long in the tooth to play Beatrice. She is one of my dream roles because she is brilliant and funny and fierce. And she feels like an outsider, which is the story of my life in many ways. So, I knew that I wanted to be involved with this play in some way. Also, coming out of this pandemic, I wanted something that was joyous and funny.

I have an idea to represent different stages of love on stage. We often get caught up in the ingénue characters in Shakespeare and the beauty of young love: the Juliets and the Rosalinds. Not to take anything away from them, but we know that love continues and endures and changes. Love moves to fit the mold of the lives of those who share that love. I want to show a more mature idea of love through Beatrice and Benedick that could still be romantic and sexy. This brings me back to August Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean. At the Goodman, I played Ester, who is ostensibly in her 60s although she is actually 285 years old. In the play, she and Solly have a wonderful, flirting romantic relationship. They are both senior citizens, and I thought about how we do not see enough of that onstage.

KN: Much Ado about Nothing has a double plot of two love stories that are happening at the same time, so this play seems especially well suited to draw out the contrast in love at different phases in life. The tone and texture of the romantic relationship will be different for Beatrice and Benedick compared to Hero and Claudio.

LD: Right. An audience member in their 50s might think wistfully back on their youth when they see Hero and Claudio, but then might have discovery—a surprise in the moment—about who and where they are now. That possibility for discovery is not only for the young but can be for all of us at any time.

KN: I have a question about Beatrice and Benedick. They are some of Shakespeare’s most famous romantic scene partners, so to speak. But I find it interesting that unlike many other Shakespearean couples, they do not fall in love at first sight. Rather, they start the play hating each other. Seeing how they change is what I find most fascinating about these two characters.

LD: And fulfilling, I think. Fascinating and theatrically fulfilling—because they have to go on a journey and overcome obstacles. For characters like Romeo and Juliet who fall in love at first sight, the obstacles have to be external. For Beatrice and Benedick, they are their own obstacles. Part of the reason is because they are fully their own selves. My assumption is that anybody who has been in a relationship that has endured past trials and tribulations can recognize that it is often the internal obstacles that are the most fraught. How do we learn to get along? I love you, and yet there is a part of you that is reflected in me that I do not like very much. Or perhaps I am wary of you because you see something in me that no one else sees. I think both Beatrice and Benedick are like this. They are both wary of each other because each of them subconsciously recognizes that they have something that the other needs to make them—not whole, because they are a whole person—but greater than the sum of their parts.

KN: Ironically, then, not falling in love at first sight could be a testament to that perceptiveness towards each other.

LD: Right, they are not falling for just a pretty face. Claudio speaks nary a word to Hero but sees that she is beautiful and falls in love with her, which is how Romeo sees Juliet or Orlando sees Rosalind. That is what I think is so satisfying about Beatrice and Benedick’s love story. Even in Taming of the Shrew, Kate is a woman who knows what she wants, but she is a prisoner within her own community and becomes embittered in a way. And therefore, she is ostracized and has to be tricked into falling in love. Of course, Shakespeare was smart enough to leave the ending a little ambiguous: is she “tamed” or not?

KN: I’m glad that you brought up Kate and Petruchio in Taming of the Shrew because it makes an interesting comparison to Beatrice and Benedick. There is that ambiguity you mentioned at the end, but Kate and Petruchio’s relationship is still framed as a kind of competition. There is a winner and a loser in that fight. Beatrice and Benedick start out as a battle of wits, but they transcend that by the end.

LD: Yes, it starts with them trying to best each other verbally, cerebrally. When I read books and plays, I find it interesting to imagine the characters well beyond the end of the story. And Beatrice and Benedick are the kind of people who will have a marriage that I am sure is volatile at times, yet steadfast in their love because each has to let the other be completely themselves. If Benedick were to want Beatrice to be less-than, he would not be for her. If Beatrice were to want him to be less-than, she would be bored with him.

KN: I have another question that goes back to some of the experiences you shared about cross-gender casting. In our production of Much Ado about Nothing, Hero’s father Leonato will be changed into her mother because a female actor is cast in that role. So, compared to the play that Shakespeare wrote, you could say that the setting becomes more of a feminine space or a women’s space. We will probably have a few scenes with only women onstage. I am curious to see how those changes will affect the story. How do you approach cross-gender casting in general? I can think of two philosophies. The female actor can leave the character intact and think of herself as being a man. Or she could modify the character into a woman, which might entail some changes in the script.

LD: The actor already works on a duality—as the actor at work and as the character in life. So, the question is about how the actor can work on these two levels while also working around, in, on top of, and through the societal norms that we say makes a “man” or a “woman.” And how can we remove those labels and just say person. I am interested in doing all-female versions of Shakespeare plays not because I want to keep men out or balance out the all-male historical reconstructions that are sometimes done. I work on these projects because—and I do this in my acting classes as well—I want women actors to use the entirety of their skills and abilities: using the strength of your voice, how you take up physical space onstage, how you move through space, how you move around others, how you demand in your conversations with others. And I want them to do these things regardless of how they might be gendered in society. There is an assumption that capitulation is feminine, and assertion is masculine. But does not Beatrice already demonstrate that one can be both feminine and assertive?

KN: I see that. I guess I was wondering more about the scenes where Leonato acts as a particular kind of father to Hero. When Claudio accuses Hero of being unfaithful, Leonato in Shakespeare’s play condemns his daughter at first, railing that he wants to renounce her. Later in the play, Leonato has this passionate speech about how no father would calm down when their child has been so wronged. I am curious what will happen when it is a mother uttering these words instead of a father.

“I want women actors to use the entirety of their skills and abilities: using the strength of your voice, how you take up physical space onstage, how you move through space, how you move around others, how you demand in your conversations with others.”

LD: The truth of it will still be there, and there are plenty of unaccepting mothers as much as fathers. It might be more expected of a father figure to rail about this injustice because it connected to his own honor. For a mother, it is still connected, but in a different way. It might be more painful because, in a way, it is the self rejecting the self. There should be layers of interpretation, where theater artists and audiences all understand the text, but also recognize that there is this other level. Since this is a woman playing the role, what does that say? Not all of it is conscious, of course. I think it should feel different and also the same. I do not know how else to put it.

KN: No, I think that makes perfect sense. For an audience member who has seen other productions or film adaptations of Much Ado about Nothing, they will recognize the scene and the emotional core of that parent-child relationship. But perhaps they will see another layer that they had not thought about before in our production.

LD: Someone might have seen Much Ado about Nothing five times, but not in this way. That can deepen your understanding not only of this particular story, but also this story as a representation of how we are as human beings as we move through the world.

KN: I am very excited to explore all of those possibilities together in rehearsal. Before I wrap up, I will say for the record that I do not think it is impossible for you to play Beatrice in a production of Much Ado about Nothing. I mean, there was the recent film adaptation of Macbeth with Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand in the leading roles. It can be another interpretation of the play.

LD: Lady Macbeth is another dream role, by the way. Yes, you are right. It could be the director’s interpretation. I am probably leaning on the side of being too cautious. If anybody calls me and says, “We want you for this role,” I will find a way to do it.

KN: And in the meantime, you can vicariously sink your teeth into Beatrice’s character by directing the play. Well, thank you so much. This was a lovely conversation.