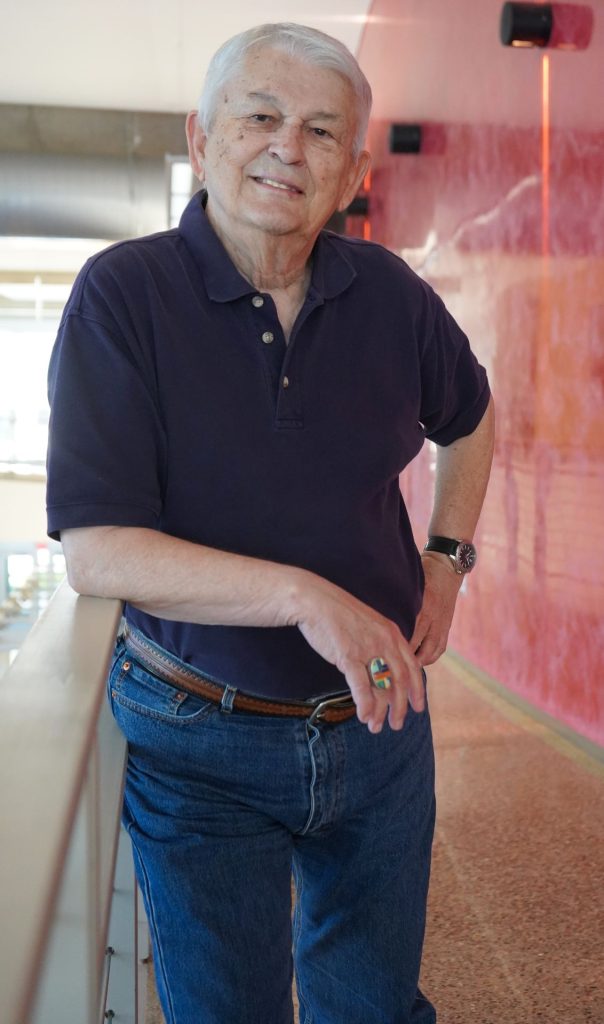

It’s a weekday afternoon in early October, and Dr. R. David Edmunds, M.A. ’66, LL.D. ’02, sits in a comfortable chair in his living room, surrounded by a spiderweb of cords. Headsets connected to laptops. Microphones plugged into mixing boards.

It isn’t an unusual state for the front room of his suburban Dallas home.

“There was a group here on Wednesday recording for a podcast. The History Channel was here on Monday,” Edmunds says casually. “I still do a lot of the talking head stuff.”

Edmunds is a well-known and trusted expert in Native American ethnohistory. He’s acquired the status through more than a half century of teaching. His scholarship has produced 10 books and more than 100 academic articles and varied roles as a contributor and supervisor to projects like the PBS docuseries We Shall Remain.

“I’m an American historian with a specialty in the American West,” he explained. “But my real specialty is the history of Native American people, tribal people, and particularly the tribal people of the Midwest.”

Edmunds is part of that history. He grew up in Blue Mound, a village about 15 miles southwest of Decatur, the great-grandson of Pachiee Westbrook, a woman of three-quarters Cherokee ancestry who spoke fluent Cherokee and broken English.

Edmunds studied at nearby Millikin University. With a bachelor’s degree in hand, he landed a teaching job at Bloomington High School in 1961. Edmunds earned a master’s degree at Illinois State University in 1966, taking classes at night and over summer breaks. He completed a master’s thesis on the history of the Kickapoo people while simultaneously researching his own lineage.

Edmunds earned a doctorate in American history from the University of Oklahoma and later served as acting director of the McNickle Center for the History of the American Indian at Chicago’s Newberry Library. He has held professorships at: the University of Wyoming; Texas Christian University; the University of California, Berkeley; UCLA; Indiana University; and the University of Texas at Dallas.

He’s earned awards for teaching, writing, and research. He served as president of the Western History Association and the American Society of Ethnohistory and received an award of merit from the American Indian Historians Association. He earned an honorary degree from Illinois State in 2002 and its Distinguished Alumni Award in 2012.

Though he retired from teaching in 2015, Edmunds keeps plenty busy. His expertise is in high demand, especially as awareness and interest in Native American history grows in association with Indigenous Peoples Day in October and Native American Heritage Month in November. He’ll soon publish another book, Voices in the Drum: Narratives from the Native American Past, his first foray into historical fiction.

Edmunds thinks Voices in the Drum will have a broader appeal than his previous works. “It’s written to engage the audience and sort of whet their appetite for further reading,” he said, hopeful the book’s narratives encourage readers to educate themselves in Native American history.

Edmunds subscribes to the notion that cultures that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it. His teaching and scholarship have largely been driven by the concept.

“Most of the reservations that remain in the United States are areas that non-Indians have not really wanted. If you look at the Midwest, most of the tribal reservations that remain are in the northern areas of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan—and that’s not where the good farmland is in those regions,” Edmunds said. “When tribal people have occupied lands with resources, mainstream culture has gobbled them up.”

Seeing potential for history to repeat itself, Edmunds offers his services as a consultant to tribes to defend land and sovereignty. He sees the next wave of struggles to be over control of water.

“We’re beginning to see that along the Colorado River now,” he said. “But we’re going to see it in a lot of other places, too.”

Edmunds described his consulting work as rewarding, as it combines his talents as a historian with his passion for preserving a way of life for Native American people.

“It allows me to apply the skills I have learned as a historian, looking up treaties and all the different articles of treaties, and how they’re interpreted, and what courts and people have said dating back to the 1830s,” he said.

As Native American Heritage Month is celebrated this November, Edmunds hopes people will consider—or perhaps reconsider—their perception of modern Native Americans.

“We’re often seen as something of the past—in other words, vanishing Americans,” Edmunds said. “And nothing could be further from the truth.”

Native American and Alaska Native population nearly doubled between 2010 and 2020—the population increased from 5.2 million to 9.7 million, a jump of 86.5%—according to the latest U.S. census.

“The population is ongoing, and it is here, and tribal people live all around you,” Edmunds said. “People don’t recognize them as tribal people because we don’t wear the ethnic clues that they’re looking for, but that doesn’t make us any less quote-unquote Native American. It’s just that we don’t subscribe to this stereotype that some people have of tribal people.”

Edmunds also dispels the popular belief that most Native Americans live on reservations in the American West; to the contrary, he says approximately half the Native American population lives in urban areas.

Despite ongoing threats to land and common misperceptions, Edmunds believes inroads have been made toward respectful recognition of Native American culture and history. The proliferation of land acknowledgements, wider recognition of Indigenous Peoples Day and Native American Heritage Month, and the retirement of offensive sports nicknames are signs of progress.

But Edmunds wishes there was more general recognition of the existence of modern Native Americans.

“I think it’s important to understand that many tribal people today function in the mainstream,” he said. “We still retain a strong sense of place, a strong sense of family, and certainly a strong sense of identity, and I think that’s very important.”

Edmunds also offers a reminder that Native American history is all around us—even here in Bloomington-Normal and greater McLean County.

“American history includes Native Americans, African Americans, Latinos, and all groups. We’re all part of this picture, and we’ve all contributed to the history of the United States,” he said. “This country is a blending pot of people. That’s been the strength of it, and I think that’s so important.”