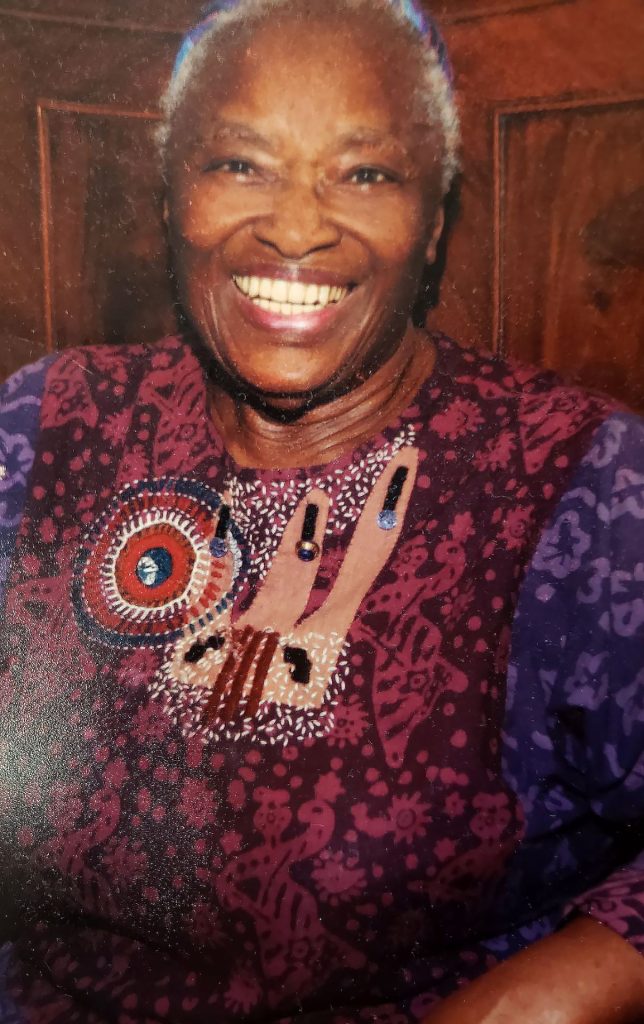

Born in 1928 to impoverished East Texas sharecroppers, Dr. Mildred Pratt fought racism, segregation, sexism, and generational poverty—among countless other obstacles—to achieve a better life and help others do the same. Education, she found, was key.

Pratt was valedictorian of her high school and earned four college diplomas, including two master’s degrees and a Ph.D. Later, she helped hundreds of students achieve their academic goals during her 24-year teaching career at Illinois State University, where in the 1970s, she became a full professor when Black women made up less than 1% of full professors nationwide.

“It’s a testament to her individual determination and perseverance,” said Dr. Menah Pratt, Mildred’s daughter and the vice president for strategic affairs and diversity at Virginia Tech University. Mildred’s other child, Awadagin Pratt, is an internationally acclaimed pianist and a professor of piano at the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music.

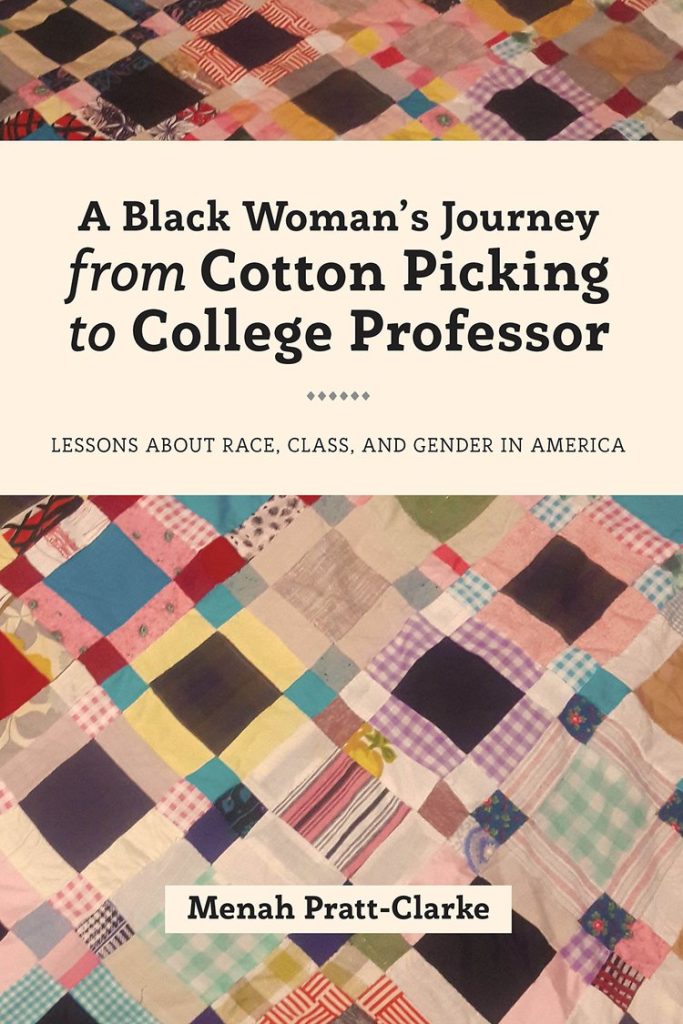

“Mildred made her mind up at one point as a child that she was going to do whatever it took, regardless of the fact that she was a poor Black girl, to succeed in life,” said Menah. She chronicled her late mother’s story in the 2018 book A Black Woman’s Journey from Cotton Picking to College Professor: Lessons about Race, Class, and Gender in America.

“She felt like nobody could take away her intellect and her commitment to excellence and actualizing her potential,” Menah said.

Mildred and her seven siblings, whose grandmother had been enslaved in Alabama, were raised during the Great Depression by their single mother. She tried, but struggled, to provide enough food for her children. Yet, Mildred thrived academically.

Recognizing her potential, a high school teacher suggested that Mildred attend Jarvis Christian College in Hawkins, Texas, a historically Black institution that allowed students to alternate working and attending school to afford tuition.

In 1951, Mildred received a bachelor’s degree in religion and sociology from Jarvis. She went on to earn a master’s degree in psychology and philosophy of religion at Butler University while working as a maid. Mildred then pursued another master’s, this time in social work at Indiana University; however, as she neared the end of her program, she ran out of money. Mildred pursued a scholarship but was denied because she was Black.

“This was still during legalized segregation,” Menah said.

Overhearing Mildred’s circumstance, a secretary at the school volunteered to finance the remainder of her education, and in 1955, Mildred earned her second graduate degree.

“That’s why she was able to graduate and finish at Indiana, and that’s why she started the Mildred Pratt Student Assistance Fund at ISU, because of that experience,” Menah said. “She was like, ‘I’m here because someone else helped me.’”

After earning a Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh in 1969, Pratt was hired by Illinois State University’s Department of Sociology and Anthropology to become the first full-time faculty member in the department to teach social work.

“She wanted social work students to understand that it’s about helping others and empowering others who may be more disadvantaged or less empowered in society.”

Dr. Menah Pratt

“She wanted social work students to understand that it’s about helping others and empowering others who may be more disadvantaged or less empowered in society,” Menah said.

As a teacher, Mildred introduced her students to active, engaged social work. She designed a class in which students interviewed marginalized community members—to “talk, listen, and learn.”

“I think she really wanted to empower, not just students, but also because she felt that elderly African Americans had been discarded in life,” Menah said. “It was like society told them, ‘What you have to say—it’s not important. You’re not degreed. You don’t have educational credentials. So, what you say isn’t important.’ And I think she wanted to show her students that knowledge and education is not dependent on a degree.”

Born in 1967, at the cusp of the Civil Rights Movement, Menah reminisces fondly about growing up in a yellow, three-bedroom ranch home surrounded by apple trees on Hovey Avenue—a quick bike ride away from campus—in Normal. She remembers watching her mother seated on the living room floor grading papers in front of her favorite flowery green and yellow armchair, which she seldom actually sat in.

But despite Mildred having earned four degrees and a faculty position, she continued to face injustices. When her tenure was initially denied at the University, she wrote to then President David Berlo to make him aware of the “institutional racism” she was experiencing in her tenure case.

“What you describe as inefficiencies—it’s deliberately built-in stumbling blocks. I refuse to settle for this,” she told him.

Eventually, Mildred earned tenure and remained at Illinois State until retiring and being named a professor emeritus in 1993. In addition to her teaching and research contributions, Mildred co-founded the Bloomington-Normal Black History Project in partnership with the McLean County Museum of History. She interviewed, in collaboration with Illinois State and Illinois Wesleyan partners, nearly 100 elderly Black residents about their life experiences.

“She wanted these older African American people to feel empowered and to feel valued and heard,” Menah said. “And she wanted their stories to be told.”

As a teenager, Menah often accompanied her mother to Black History Project events or to pick up artifacts for the project’s collection, such as military uniforms or lace dresses. She also read many of the Black History Project narratives.

“Mama would occasionally mention how hard it was for some of the people she interviewed to tell these stories, because they were so painful,” Menah said. “It was just a constant example of dehumanization.

“And I think that just made me develop a lot of empathy and compassion for people in terms of really appreciating how racism impacts a person. It’s a thing that touches people and impacts and causes pain. And I think just reading a lot of the interviews—I saw that pain, but I also realized how important it was to understand African American history and the successes and achievements.”

Menah said Mildred, who passed away in 2012 at the age of 83, instilled in her a drive to achieve academic excellence and leave behind a legacy. Along with establishing her student assistance fund at Illinois State, Mildred also collaborated with some of her Bloomington-Normal friends to found the Pratt Music Foundation, in memory of her husband of nearly 32 years T.A.E.C. “Ted” Pratt. The Pratt Foundation promotes classical music education for local youth by providing scholarships for music lessons.

“When I think about my mother, I think about the importance of Black women telling their own stories and having something tangible to pass to the next generation about challenges, successes, failures, opportunities, and lessons learned.”

Dr. Menah Pratt

“When I think about my mother, I think about the importance of Black women telling their own stories and having something tangible to pass to the next generation about challenges, successes, failures, opportunities, and lessons learned,” Menah said.

Mildred imparted wisdom through videos that she recorded as an 80-year-old featuring poems and songs, available to watch on YouTube. Her life story included three visits to the White House in Washington, D.C., to hear her son, Awadagin, play piano for Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. She loved traveling and playing tennis, and she met Richard Williams, the father of tennis stars Venus and Serena Williams, at the US Open.

And, through her decades of teaching and mentorship, Mildred—who petitely stood at 5 feet tall—made a gigantic impact on her students and colleagues.

“That personal impact of her life on others, I think is really important and made an impact on me,” Menah said. “And so, I make sure that the work I do is impactful and makes a difference on the humanity of other people—the sensitivity to issues of race and gender, what it means to be a Black woman, and the level of fortitude and determination and persistence we have to have as Black women to succeed.”

Menah shared her passion and expertise with the Illinois State University community during a November 17, 2022, workshop titled “Envisioning and Implementing Social Change for Sustainable Campus Transformation.”

By continuing to tell her mother’s story, Menah said she hopes Mildred’s journey provides inspiration and hope to individuals facing seemingly insurmountable personal challenges.

“Even in the midst of difficult circumstances, you can thrive and survive,” Menah said. “You can be aware of, and sensitive to, and compassionate with other people. And you can have joy in your own life—because Mama was a very joyful person, and she enjoyed hosting parties and events for her friends and family.

“Mama’s life answered the question: ‘So, how do you actualize your own potential so you can help others to actualize theirs?’ That’s what she stood for.”