In the character list for Lauren Gunderson’s play The Book of Will, Ben Jonson is described as “Poet laureate of England” and a “friend/rival of Shakespeare.” The first label reflects Jonson’s status as a celebrated writer with connections to the royal court and social elite—“Britain’s first literary celebrity,” as biographer Ian Donaldson puts it. But despite enjoying prestige and success during his lifetime, Jonson’s reputation is now overshadowed by his contemporary William Shakespeare. That takes us to the second part of Gunderson’s character description. Shakespeare and Jonson’s relationship is almost always described in mixed terms; they are never simply friends, but not quite enemies either. Who exactly was this ambitious, testy writer, and how did he cross paths with Shakespeare?

Perhaps Shakespeare and Jonson are often seen as rivals because, as far as we can tell, their personalities were diametrically opposed to each other. It seems that Shakespeare did not like drawing attention to himself, whereas Jonson enjoyed being in the spotlight, understanding the importance of self-promotion in early modern London society. Jonson’s published works are full of his own commentary—prefaces, defenses against critics, footnotes, etc.—while Shakespeare either let his writing speak for itself or did not care what readers thought. Shakespeare was frugal and kept himself out of trouble. Jonson, on the other hand, was known to be a heavy drinker and was jailed several times, in one instance for killing an actor in a fight. He narrowly avoided execution.

Despite these differences, Shakespeare and Jonson were friends. Jonson wrote a long eulogy for the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio, full of memorable one-liners such as: “He was not of an age, but for all time!” Of course, Jonson does not miss the opportunity to take a friendly jab as well, pointing out that Shakespeare had “small Latin, and less Greek.” Another piece of evidence that alludes to the two men’s friendship is a story in that Shakespeare allegedly died from a fever after drinking too hard with some friends, including Jonson, who visited him at Stratford-upon-Avon. This account first appears in writing almost 50 years after Shakespeare’s death, so its credibility is questionable. But if it is true (and we have no other records that might explain why Shakespeare died at the age of 52), it suggests that the two stayed in touch even after Shakespeare retired and left London.

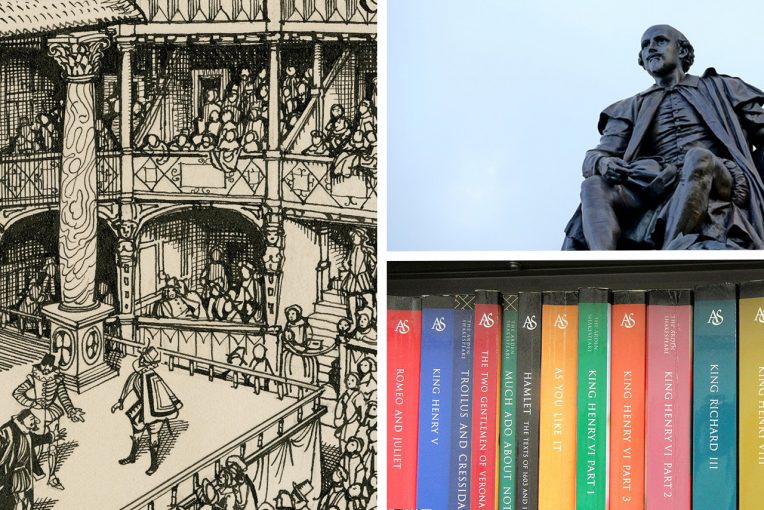

Shakespeare and Jonson probably met in the mid-to-late 1590s, when Jonson started writing plays for professional theatres. The young Jonson had no intention of taking on his stepfather’s bricklaying trade and saw writing as a means to climb the social ladder. Perhaps Shakespeare, the son of a glovemaker, saw a bit of himself in the aspiring playwright eight years younger than him. After all, Shakespeare left his hometown and family to write for a living. In 1598, Jonson’s breakout hit comedy Every Man in His Humour was staged by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men with Shakespeare in the cast. The published version of the play lists the primary cast members, and Shakespeare’s name is on the top row alongside Richard Burbage, hinting that he may have played a large role. Around this time, Shakespeare was exploring a different style of comedy in plays such as As You Like It and Twelfth Night. Shakespeare’s comedies favored romance and faraway locations, while Jonson was gaining a reputation for urban satire.

Except for a few attempts at writing poetry to gain patronage (possibly while the playhouses were shut down during the plague), Shakespeare focused exclusively on the stage, churning out approximately two new plays a year for most of his career. Jonson, on the other hand, had his sights elsewhere. Jonson often spoke disparagingly about theatre, writing once that the stage is where “nothing but the garbage of the time is uttered.” Jonson curried favor with the social elite through his poetry and saw an opportunity when King James ascended to the crown. By working his way into the King and Queen’s circle, he was able to write the text for the many lavish and expensive entertainments—called masques—that the royal court commissioned. Jonson collaborated with the famed scenic designer and stage machinist Inigo Jones on these spectacular performances. Apparently sparks flew when their colossal egos clashed, but the two worked together on numerous masques for over a decade despite hating each other. It was probably worth it, as Jonson made much more money writing for the court than the playhouses. It also brought him the prestige and fame he always sought. In 1616, Jonson was awarded an annual pension, which effectively made him Poet Laureate of England.

Although Shakespeare did not write masques, he seems to have been familiar with the genre. The Tempest contains several play-within-a-play sequences that resemble court masques, with mythological figures addressing the onstage audience. It is possible that Shakespeare may have been influenced by Jonson’s work in court. Perhaps Shakespeare discussed masques with his friend even if he was not able to see them firsthand.

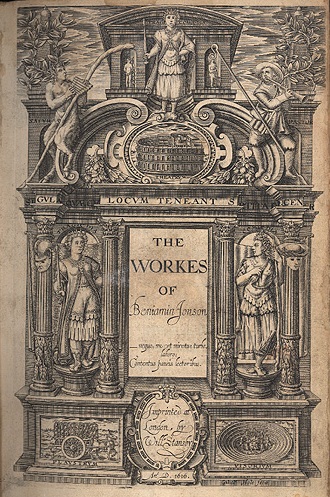

Jonson may have impacted the legacy of Shakespeare’s plays in another way as well. In 1616, the year that Shakespeare died, Jonson did something that was unheard of in the literary culture of the time. He published a folio edition of his writings, titled The Works of Benjamin Jonson. What was unusual is that Jonson included nine plays in the volume, alongside his masques and poems. Although we now have playwrights winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, plays were not considered respectable enough at the time to be counted among a writer’s literary “works.” Thus, Jonson was ridiculed harshly for this brazen choice. It was also rare to see plays printed in folio format; they were commonly found in cheap quarto editions, similar to pulp paperbacks today. Jonson was clearly making a statement by including plays in his Works. They are just as important as his other writings. They are worthy of appearing in a leatherbound, folio-size book.

Seven years later, John Heminges and Henry Condell decided to publish all of Shakespeare’s plays in a single folio volume. Of course, they do not go as far as calling the book “The Works of William Shakespeare,” opting for the humbler (and wordier) Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. As Gunderson’s play illustrates, the two men faced countless obstacles along the way. Thankfully, they succeeded in the end, which is how almost all of Shakespeare’s plays have survived while most plays written during that period are lost. But would Heminges and Condell have come up with the idea in the first place if Ben Jonson, Shakespeare’s friend, and rival, had not set the precedent?