Festival Dramaturg Kee-Yoon Nahm spoke with director Lori Adams about the upcoming production of Lauren Gunderson’s The Book of Will at the Illinois Shakespeare Festival (ISF). This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kee-Yoon Nahm (KN): Before we talk about The Book of Will, would you please recount your history with the Illinois Shakespeare Festival (ISF)? This is my fifth season as festival dramaturg, and in that time I have seen you perform onstage and direct the Theatre for Young Audiences (TYA) production. But I do not know about your involvement with the Festival before that.

Lori Adams (LA): My first year with ISF was 1998. I was the assistant text coach with Christine Sevec-Johnson. I was a young faculty member here at ISU and just wanted to learn. So, I asked Christine if I could assist her. Since then, I have done seven or eight seasons as an actor, one way or another. And I have directed the TYA shows and green shows many times. Actually, in the 1998 season, my children Anna and Nathan were in the cast of Much Ado about Nothing, and John Stark, my husband, was the scenic designer for The Falcon’s Pitch, an adaptation of the Henry VI plays. So, the whole family was in ISF. There have been very few summers where at least one of us was not involved.

KN: Aside from the TYA shows and green shows, though, is this the first time that you are directing one of the main productions?

LA: Yes. I have never directed in the season before.

KN: What is that like?

LA: It is funny. There are some Shakespeare plays that I am really intrigued by, but I have never offered to direct one of the main productions. But then I read this play, The Book of Will. And I said right away that I want to direct it if ISF does it. This is my wheelhouse. The play does a beautiful job telling the story of how Shakespeare’s plays were published, and the friendship, the family, and the legacy that comes with that story.

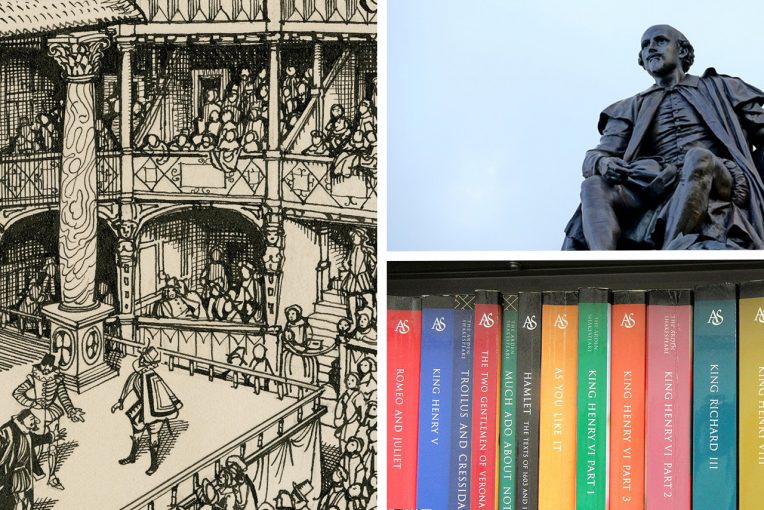

KN: The play is truly a tribute to Shakespeare’s work. Before we dive into the play, would you give me a quick summary of the premise?

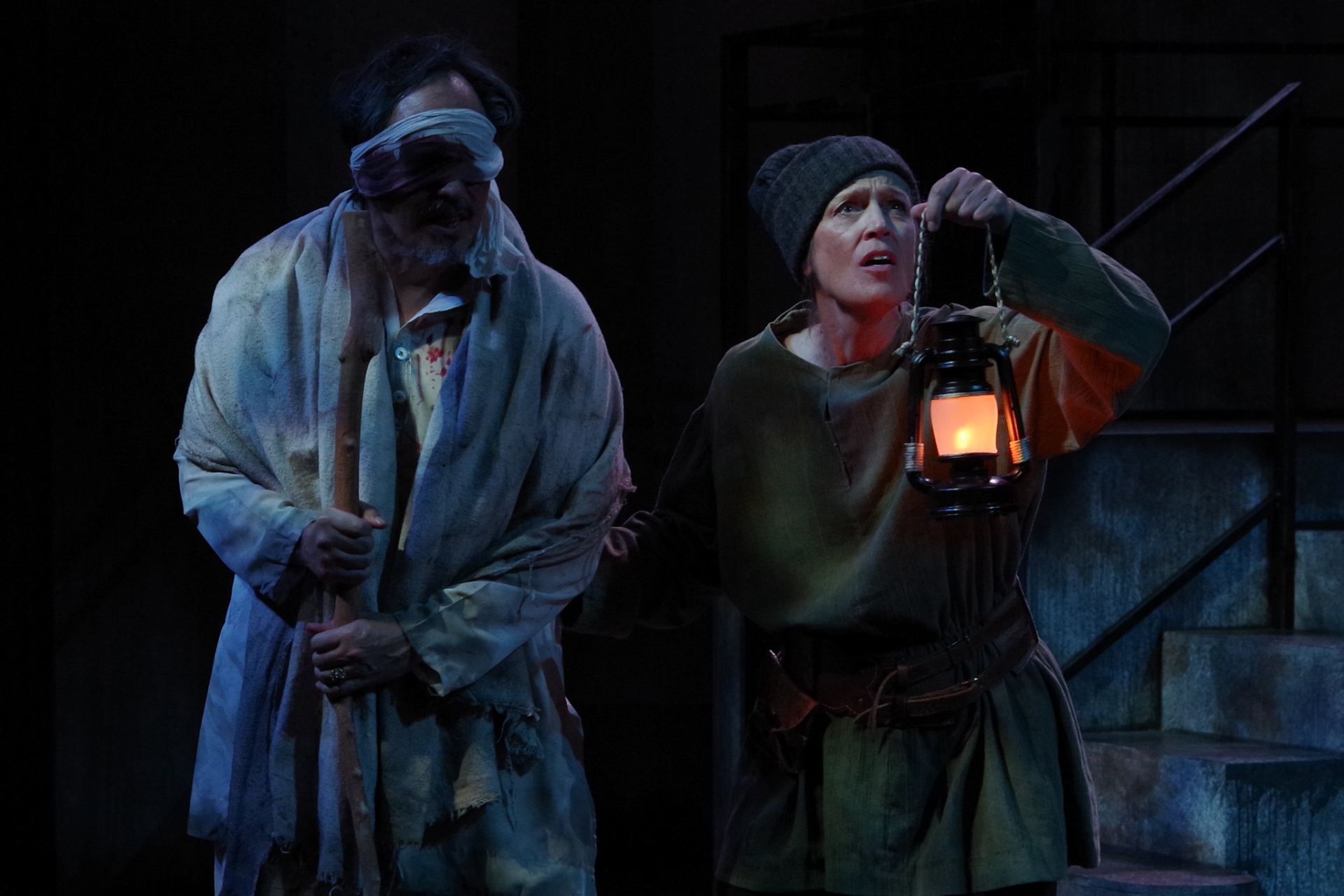

LA: Well, it is the year 1619, three years after Shakespeare’s death. The King’s Men, Shakespeare’s old theatre company, are at a bar, and Richard Burbage, the famous actor who played all of Shakespeare’s famous lead roles, has just seen an unsanctioned production of Hamlet. We learn that other theatres are performing Shakespeare’s plays—but not word for word. They are pirating them. The members of the King’s Men are livid that this is happening. But then—and this is still the very beginning of the play—Burbage dies. Two of the remaining company members, Henry Condell and John Heminges, realize that Burbage was the only one who remembered the play word for word. So, they ask: what are we going to do? These plays will disappear. The trajectory of the play is these two men trying to get all of Shakespeare’s scripts together and publish them into what we now know as the First Folio. This play is the story of how that might have happened. I am also happy to say that the playwright, Lauren Gunderson, does an excellent job of including women in the play as well. The wives of the two company members, Elizabeth Condell and Rebecca Heminges, as well as Rebecca and John’s daughter Alice Heminges, play large roles in the story. They work tirelessly against all odds to put this book together. Of course, we know they will succeed because we have the First Folio, right? But I think the play is written well so we do not know how exactly that will happen. It seems impossible. They do not have money. They know nothing about printing because they are just actors. They have trouble finding all of Shakespeare’s manuscripts. The list of problems goes on.

KN: That is a good point. I admire this play because it does what great historical fiction does. We have the facts of what Henry Condell and John Heminges did. They published the First Folio, which was actually very expensive and not a great business decision. But something must have motivated them to undertake this big project. I like that this play tries to imagine what might have driven them to keep going despite all the challenges you mentioned.

LA: But also, they are not equally enthusiastic about the idea. Gunderson sets up a nice conflict between the two main characters. They argue constantly, and yet they keep edging forward and finding a way.

KN: It is scary to think that if they had not kept going, we would have lost about half of the Shakespeare plays we currently have. Eighteen of the 36 plays in the First Folio only exist in that version from the time.

LA: It is impossible to imagine what history would have been like without those plays.

KN: You mentioned the members of the King’s Men and their families, who are at the center of the play. But Book of Will is also full of colorful characters such as Emilia Bassano Lanier, who some scholars believe is the “Dark Lady” described in so many of Shakespeare’s sonnets. There is also the poet and playwright Ben Jonson, who was both Shakespeare’s friend and rival. These characters give us a fuller picture of Shakespeare’s circle of acquaintances, as well as life in the London theatre world in the early seventeenth century. Is there a character that you are particularly interested in—someone you are excited to explore in rehearsal?

LA: I do love the two main leads. I love their friendship and camaraderie. I also love their relationships with their wives. But the secondary characters are equally enthralling to me. We have Ed Knight, the stage manager of the King’s Men—so serious and precise about everything. There is Ralph Crane, a meek man who ends up saving the day because he is aware of what is going on. Even our villain, so to speak, William Jaggard, is an interesting role because in the end, he is just trying to make some money by publishing books, including Shakespeare’s plays. Then there is Ben Jonson. The way he is written in the play is delightful. Tom Quinn will play that role, and I cannot think of anybody better.

KN: As I hear you talk about these characters, especially the ones in the King’s Men, I am reminded of where we started in this conversation—about your history with the Festival and how in some summers your entire family was involved with ISF. Now that I think about it, this is a play about theatre families as well. We tend to think of the King’s Men only as a group of men because only men were allowed to be onstage during Shakespeare’s time. But this play suggests that the company was larger than that. Their wives and daughters are just as involved in the theatre and love Shakespeare’s words.

LA: At one point in the play, Alice—John Heminges’s daughter—talks about how she was backstage during performances of The Tempest, rattling pots for the storm scene. And I know that my kids would think, ‘Yeah, that would have been us!’ Our children still come back to see ISF in the summer, even though they are grown and have lived away from home for many years. They have barely missed a season. They are planning to come back this summer. I naturally gravitate toward the theme of family, which is another reason that this play was right up my alley when I read it.

KN: I agree. But this is also a play about mourning death. I will not give away too much about the plot, but you have already mentioned that Richard Burbage dies early in the play. And you could say that the entire venture to publish Shakespeare’s plays is a way for these characters to process the absence of their dear friend. They go to such lengths because they want to honor Shakespeare’s memory. The Book of Will is a joyful and lighthearted play as a whole, but it also asks us to reflect on grief and mourning. What are your thoughts about that?

LA: I think it mirrors what we experience in Shakespeare’s plays. I recently saw a video interview with Lauren Gunderson where she talked about how Shakespeare was able to write about such profound human experiences at a relatively young age. He died when he was 52—so, not very old especially by our standards. How could he reach such depths of sorrow and despair, while also expressing such deep joy and love? How can he have anger and pain and rage in a play that also has clowns? There are many parts of this play, including the grief, that will resonate strongly with people.

“I naturally gravitate towards the theme of family, which is another reason that this play was right up my alley when I read it.”

KN: The Book of Will is quite a mature play because of the range of experiences it encompasses, but also because the major characters are in their 40s and 50s. They start to think about their own mortality as their friends pass away. And as you mentioned, they ask who will remember what we did unless we preserve it in writing. Even though this is a play about something that happened hundreds of years ago, it touches on the universal human experience of aging the desire to keep memories alive beyond one’s death.

LA: Yes, it is something we all wrestle with. And that is why we still do Shakespeare. We cannot disconnect ourselves from the things he writes about.

KN: As a director, how are you trying to bring this community of theatre people to life onstage? What is your entry point into the world that Gunderson creates?

LA: My “in” as a director is always celebrating, pinpointing, identifying, and loving the specialness of every actor. But this production is a very different experience for me. In the past, when I directed, I would audition actors in person. I would see people in the same room and put them together to see how they become a company of actors. Now, auditions are done on video. You have to feel the spirit that is coming through that little screen and assess who will fit into this metaphorical family. But I trust the actors, and I know they will bring things that I could have never thought of.

KN: Many Shakespeare historians guess that Shakespeare also had that kind of trusting relationship with the actors of the King’s Men. There are clowns even in some of the tragedies because there were great clown actors in the company, and Shakespeare wanted to make use of their skills.

LA: I bet that is true. I never put that together.

KN: And, as it is mentioned in The Book of Will, all of Shakespeare’s major roles would have been written with Richard Burbage in mind since he probably played most of them. It is fun to think about that. Sometimes we imagine Shakespeare’s plays as perfect works of art that are complete in themselves. But as a writer, Shakespeare would have been like any other playwright we know, who is constantly responding to things around them. And when you live more than two decades of your life together with the same group of people, there are probably traces of them all over the plays.

LA: I love that idea. Of course, that is what television does. They start in one place, but the writers get to know the actors better, and the series develops in response to that. It is comforting to think that Shakespeare went through the same process as any other playwright. We tend to put him on this pedestal and think, ‘Who could do this besides Shakespeare?’

KN: Yes, in reality, he was part of a thriving theatre scene in London. And I love that The Book of Will captures that environment in such wonderful detail. To wrap up, what would you like for audiences to take away with them when they see the play this summer?

“It is comforting to think that Shakespeare went through the same process as any other playwright.”

LA: The play is about friendship and legacy and history, as we talked about. But I think the play teaches you what is important about theatre, which to me is communion and storytelling, and life. I guess I want people to understand what theatre does with life and why that is fulfilling.

KN: You are right. The play pulls back the curtain and teaches us not only about the backstage business of theatre but also the emotional investment that goes into life in the theatre. Theatre becomes part of the air you breathe. Thank you!