From decades of celebrating Black History Month on Illinois State University’s campus to the University’s birthday 167 years ago, historian Tom Emery explores this month in Illinois State University history.

February 5

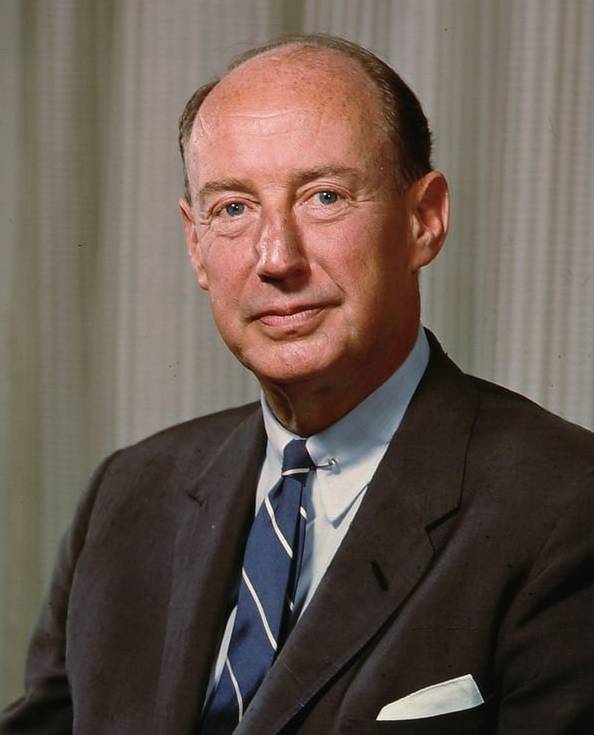

On this date in 1900, Adlai Stevenson, who served as governor of Illinois and whose name graces Stevenson Hall, was born.

A former student at the ISU laboratory schools, Stevenson was the most famous member of the Stevenson family dynasty, which remains synonymous with the city of Bloomington.

Stevenson’s paternal grandfather, also named Adlai, served as vice-president from 1893-97, while his maternal great-grandfather was the ubiquitous Jesse Fell, Abraham Lincoln’s close friend and the driving force behind the location of Illinois State in Bloomington-Normal.

Fell’s son-in-law was William Davis, the owner of the Bloomington Pantagraph, whose daughter, Helen, married Lewis Stevenson, Adlai’s father, in 1893. Lewis later served as Illinois Secretary of State from 1914-17.

For a time, Lewis and Helen lived in Los Angeles, where their second child, Adlai II, was born on February 5, 1900.

Young Adlai attended both of the Illinois State Normal laboratory schools, starting with the Thomas Metcalf School for elementary students. He followed with three years at University High School before completing his college preparatory education at Choate in Wallingford, Connecticut.

In 1948, Stevenson rolled into the Illinois governor’s mansion by over 572,000 votes, a record for that time. Stevenson’s landslide, coupled with his previous Washington experience, earned a groundswell of support among Democrats for the 1952 Presidential nomination.

Among his most devoted backers were President Harry Truman and former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. During his acceptance speech at the convention that July, Stevenson famously said, “let’s talk sense to the American people.”

Though he had wished to remain governor, Stevenson reluctantly threw himself into the campaign, which was headquartered at the Leland Hotel in downtown Springfield. He traveled 32,000 miles and delivered 203 speeches nationwide but still lost decisively, winning just nine states and 89 electoral votes against the wildly popular Dwight Eisenhower.

Stevenson conceded the election from the Leland Hotel’s ballroom at 12:40 a.m. on election night. He said that he “was reminded of a story that a fellow townsman of ours used to tell—Abraham Lincoln. He said he felt like the little boy who had stubbed his toe in the dark. He said that he was too old to cry, but it hurt too much to laugh.”

Despite the resounding loss, Stevenson was the clear favorite to win the Democratic nomination again in 1956. He faced even longer odds against an incumbent Eisenhower, and was hampered by a severe lack of campaign funding. In the end, Stevenson lost even worse than in 1952, collecting only 42% of the vote and seven states.

Still, there was glory in defeat—a rarity in politics today. Roger Biles, a member of the history faculty at Illinois State, wrote in 2005 that Stevenson’s “carefully crafted speeches, infused with wit and reason, elevated the tone of political discourse” and “won the respect and admiration of the American people.”

On January 23, 1961, Stevenson was appointed Ambassador to the United Nations, serving during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

Stevenson died of a fatal heart attack on July 14, 1965. His funeral was held in Bloomington at the Unitarian Church, with President Lyndon Baines Johnson among those in attendance. A crowd of 6,000 later attended a Stevenson service at Horton Field House on the Illinois State campus.

The legacy of Adlai Stevenson is found nationwide in a multitude of grade schools and major thoroughfares named in his honor. In 1965, the United States Postal Service issued a five-cent stamp to commemorate him.

At Illinois State, Stevenson Hall opened in 1968, and now houses the College of Arts and Sciences. There is also the Stevenson Center for Community and Economic Development, established in 1994 to promote public service and global understanding. The center marked its 25th anniversary in October 2019 with the appropriately named “Adlai Week.”

February 9

On this date in 1913, Martha Haynie, one of the first female professors in Illinois State history, died in Chicago. Haynie Hall, in the Tri-Towers complex, is named in her honor.

Haynie arrived in Normal as the University was still in its infancy. Born on June 3, 1826, in Danville, Kentucky, she was the daughter of a physician who had studied under the renowned Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Haynie studied foreign languages, particularly French, to prepare herself for a career. At age 20, she moved with her family to Mount Vernon, then taught for two and a half years before marrying Dr. Abner Frost Haynie of nearby Salem, a respected doctor, in 1849. However, her husband died just two years later.

In 1856, Haynie returned to teaching as an assistant at the Mount Vernon Academy, where she spent a year before taking charge of a new girls’ school. Haynie remained in Mount Vernon until 1866, when she accepted a position as assistant principal in the ISNU high school department.

Along with her administrative duties, Haynie taught English grammar, French, rhetoric, and composition in the high school through 1876, with considerable success. A 1907 university history writes that “every student of the school…has a warm place in [their] heart for the woman who was as true a friend to every boy and girl enrolled in her classes as the fortunes of life can possibly bring.”

In 1876, Haynie was appointed to the Professorship of Modern Languages at the university level. She remained in the position for a decade, constantly impressing students and peers with her skill and efficiency. Meanwhile, she somehow found the time to author two books. The 1907 history marveled at “how she managed to accomplish the amount of work that she carried through with such an abounding energy.”

That account continued that Haynie “was far more than a mere classroom instructor; she was a devoted friend and was never weary of serving those who were under her charge.” Still, her imposing presence may have intimidated some newcomers. Charles Fordyce, a member of the class of 1882, remembered entering Haynie’s class as an incoming student, and that “the first half-hour’s experience paralyzed me.”

After her resignation in 1886, Haynie moved to Chicago and resided with her son. She apparently enjoyed good health at an old age, particularly for the time; the 1907 history wrote that “her penmanship is without the faintest suggestion of [tremor], and her well-known intellectual vigor is not impaired.”

Martha Haynie’s death in 1913 was met with regret by her many friends back in Bloomington-Normal, as well as countless former students. An obituary in the Bloomington Pantagraph lamented that “she will be kindly remembered by scores of former pupils throughout the state.”

February 10

February is Black History Month, the origins of which date to 1926, when scholar Carter G. Woodson, who dedicated much of his life to the promotion and preservation of the subject, initiated Negro History Week. Harrison set the date as February 7-13, or the second week of February, to include the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

Twenty-nine years earlier, teacher and activist Mary Church Terrell had persuaded the Washington, D.C., school board to set aside the afternoon of February 14, 1897, to learn about and celebrate Frederick Douglass’s life.

On this date in 1976, President Gerald Ford officially recognized Black History Month. However, the observance of African American history had been previously celebrated in some locales across the United States for decades, including at Illinois State.

The first reference to Negro History Week in the Vidette was a detailed article on February 9, 1931, which discussed such luminaries as poet Paul Dunbar, writer Charles W. Chestnut, and scholar W.E.B. DuBois. The article was titled “’Negro Renaissance’ Resulting in Valuable Contributions in Numerous Cultural Fields.”

Commemorations of Black History at Illinois State grew with the years and, by 1975, it was a major event on campus. That year, activities included an African American film festival, an appearance by a senior editor of Ebony magazine, and salutes to Marcus Garvey, Frederick Douglass, and others.

A thought-provoking editorial in the Vidette on February 8, 1980, declared that “Black History Week Not Just for Blacks,” noting “it’s for all students, faculty, and staff.” The editorial opened with a statement that summarized the reason for the celebration; “Black Americans enjoy and have suffered a much different history than other groups of Americans.”

The crowning event of Black History Month in 1989 was the official opening of the Rosa Parks Room in Watterson Towers. The event featured a stirring address from Dr. Sharon Whittaker, Ph.D. ’83, the dean of student services at Paine College, a private historically Black Methodist college in Augusta, Georgia, and a former assistant director of the Office of Residential Life at Illinois State.

Among her many highlights, Whittaker stated that “I am one of the many who felt one month is not enough. Every day should be Black History day” because “an uninformed and misinformed mind is an ignorant [mind.] To err is human but to remain in error…is stupid.”

Whittaker also urged for everyone to “strive for human oneness. We need each other.” It was a poignant moment that has come to define the meaning of Black History Month at Illinois State and elsewhere.

February 18

Today is the official birthday of Illinois State, as the University was signed into law on this date in 1857 by Illinois Gov. William Bissell. The move created the first public institution of higher learning in the state of Illinois.

Earlier that day, the bill to establish the University had passed the state legislature. The bill also created the 15-member Board of Education, which oversaw the University in its infant days.

Samuel Moulton of Shelbyville, who became a member of the Board, had introduced the so-called “Normal School Bill” in the Illinois House, while Joel Seth Post of Decatur introduced a corresponding bill in the state Senate. Passage of the bills, particularly in the House, was surprisingly close.

Support in the legislature for the bills was mainly from northern Illinois, as many lawmakers from southern Illinois opposed the measure. Thirty-eight votes were needed for passage in the House, and the bill squeaked by with just a vote to spare, 39-25. By contrast, the Senate passed the bill 16-4.

The passage created a whirlwind of activity to get the fledgling school up and running. The Board of Education met for the first time on March 26, 1857, and by May, Bloomington had been chosen as the site for the new university. A president, Charles Hovey, was selected on June 23 by a close 6-5 vote.

It was determined to start classes in the fall, and Hovey was faced with a mammoth task. Among the many needs were development of a curriculum, the hiring of faculty, the securing of acceptable physical facilities, and basic needs like chairs and desks.

With great effort, Hovey and his trusty assistant, Ira Moore, managed to pull it off. Classes opened in Major’s Hall on Oct. 5, 1857—just three and a half months after Hovey was appointed to the position.

Today on the campus, February 18 is celebrated as Founders Day, a tribute to the birth and earliest days of the University, as well as the sweeping legacy it has created throughout the 167 years of its history.

February 29

Editor’s note: This post includes gendered language from historic Vidette articles. Illinois State University uses inclusive language as outlined in our Editorial Standards.

This day, which occurs every four years as Leap Year or Leap Day, is an oddity on the calendar and, not surprisingly, Illinois State students of the past found unusual ways to celebrate.

Through the centuries, Leap Year draws chuckles and smirks, and has given rise to quirky traditions. In British lore, Leap Year is the only day on the calendar that a woman may propose to a man, which gave rise to the American version of Sadie Hawkins Day.

That custom—when a girl asks a boy to a dance, rather than the other way around—became the basis for many of the Leap Year festivities at ISU. In many instances, ISU students celebrated at different times throughout a Leap Year, not always on February 29.

In February 1888, the Vidette reported that “the Leap Year parties in town have had an uninterrupted reign,” as “the fair participants [a colloquial term for the women] do not seem to weary footing up the bills.”

Among the popular activities in 1888 were “sleighing parties,” though one campus club suffered a mishap when a sled overturned “and one of the young ladies was seriously injured.” A more sedate activity was dinner, with a favorite delicacy of the day—oysters.

In a time of strict gender roles, it was not always easy for women to make the first move. In 1904, the Vidette joked that “during the week preceding” the Leap Year party, “girls looking for ‘bundles’ of courage” were easy to find.

Dancing was a popular pastime of the era, and for the Leap Year dance in 1916 in the gymnasium, 27 couples showed up. In 1924, the Women’s Athletic Association hosted a Leap Year dance, which had an element of formality. Attendees were treated to a lecture at the event on “The Proper Forms of Dancing.”

The Leap Year of 1936 apparently slipped by the campus, so a belated Leap Year dance was held in January 1937. As the headline in the Vidette noted, “A Little Late But Women Will Have Their Leap Year Fun.” Leap Year dances were not always free; admission in 1960 was 30 cents, a fee that rose to 50 cents four years later. But the tradition endured, and Leap Year dances and gatherings were still reported in the Vidette into the 1980s. Although it happens only once every four years, Leap Year was a big deal at Illinois State for decades, and still draws a smile from students today.

Tom Emery is a freelance writer and historical researcher who, in collaboration with Carl Kasten ’66, co-authored the 2020 book Abraham Lincoln and the Heritage of Illinois State University.