In the fourth installment of Milner Library recognizing the women of Illinois State Normal University and to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies program, this article focuses on an ISNU alum who is known as a hero in China. The Illinois State Historical Society named April 12 Minnie Vautrin Day to commemorate the her actions in protecting ten thousand Chinese women and children during the Imperial Japanese occupation of Nanking during the Sino-Japanese War in the late 1930s. The College of Education recently started the Minnie Vautrin Memorial Scholarship in her honor. This article is a summary of Vautrin’s life from American Goddess at the Rape of Nanking: The Courage of Minnie Vautrin by Hua-ling Hu, but not a full description of the horrors of the Nanking Massacre and the Sino-Japanese War. Please see additional resources at the end for further reading. Content warnings for sexual abuse and suicide.

Wilhelmina “Minnie” Vautrin was born on September 27, 1886, in Secor, Illinois. Vautrin began her education at Illinois State Normal University in 1903 and graduated in 1907 after having to take a few semesters off to save for tuition and expenses. Her first job was as a high school teacher in LeRoy, Illinois, and she attended the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign a few years later to obtain her Bachelor of Arts in education, where she was introduced to the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions. Christian Missionaries were a popular and easy way for women to travel, and a “fulfillment of idealism for young people, who intended to save the world” by spreading the Christian faith (Page 4). These missionary groups were geared towards women, who were not welcome at the pulpit for regular Sunday service, and it offered them a career path that was not teaching. They attracted young, single women who had a “pioneer spirit” (Page 13). According to Hu’s book, “Minnie fit into the picture. Being raised on her father’s small farm, she was courageous, determined, and devoted to serving the neediest” (Page 13). Evangelizing in China was a new and exciting location because the Student Volunteer Movement was marketing it as a “godless” country in need of saving (Page 5).

Upon graduation, Vautrin joined the Foreign Christian Missionary Society when she was 26 years old in 1912. She was sent to Hofei in the Anhwei Province and experienced a profound culture shock. Education for girls was nearly nonexistent and was left up to the parents, following the belief that “ignorant women were virtuous women” (Page 14). Christian missionaries were vital in persuading the Chinese government to open schools for girls and women. Vautrin spent her first few months advocating for girls’ education, and she established the San Ching Girls’ Middle School in Hofei (Page 15).

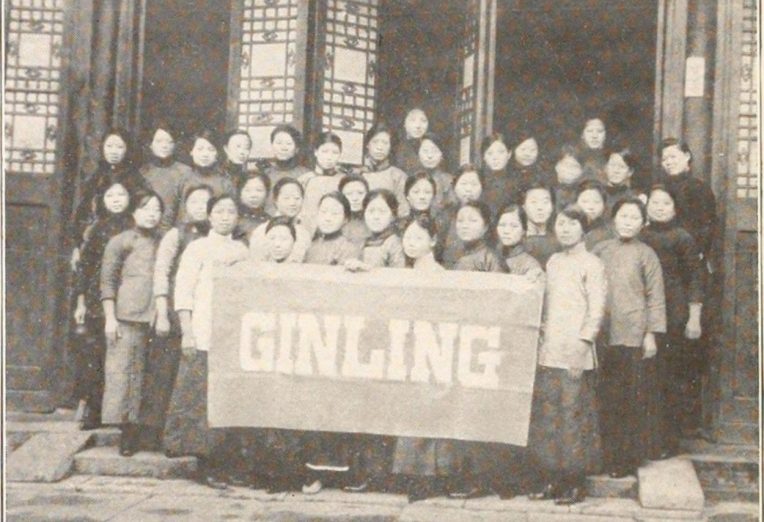

She returned to the states on furlough in 1918 to visit home and to attend Columbia University for her Master of Arts in education (Page 19). The Mission was originally going to send her to Nantungchow to establish another girls’ school, but the Ginling College for Women in Nanking asked her to be acting president for one year while their current president was on furlough (Page 19). Although she was eager to go to Nantungchow, Vautrin recognized the need for her help at Ginling, and wrote she would go, only if there was “absolutely no one else to do the work … I do not want Ginling to suffer if you do not succeed in finding anyone else” (Page 20). Both the Mission and Ginling were desperate for her expertise, but the Mission eventually relented.

She officially accepted the position as acting president in September 1919, and wrote in a letter that she was “delighted with what [she] has found at Ginling” (Page 22). She hired teachers, added courses, and implemented a student teaching program that had never been used in Chinese colleges. She helped raise funds, design buildings, and supervise construction for a new campus on the west side of Nanking. Vautrin also took interest in the community. She taught Sunday school, facilitated free health clinics, and opened a coed elementary school affiliated with the college for the children in lower income neighborhoods (Page 23-24). The town grew to love and depend on her and called her “Miss Hua” for her Chinese name, Hua Chuan.

She took another furlough in 1925 and visited her brother and father at their new home in Shepherd, Michigan. She moved her aging father with her to Chicago where she attended graduate school at the University of Chicago for education. She wanted to spend as much time with him as she could since his health was failing and she was always away, but her father struggled with loneliness in Chicago (Page 25). She was busy attending classes, continuing work for Ginling, and tirelessly writing to sponsors for more money.

Vautrin returned in 1926 to an anti-Christian movement in China, and the beginning of unrest in Nanking. The government demanded the registration of missionary schools to control the curriculum and reduce religious teaching, but Ginling refused. On March 24, 1927, the Nationalist Revolutionary Army, affiliated with the Chinese Communists in South China, started attacking foreign establishments, including the University of Nanking. An officer of the nationalist army spared Ginling because his sister attended the college (Page 34-35). Ginling opened in the fall for students, but it was the start of a very tumultuous ten years.

In 1937, Vautrin’s father died, and Imperial Japan attempted to have a military exercise on the Lugou Bridge near Beijing, but the Chinese rejected it. This incited what is now known as the Lugou Bridge Incident, also known by its Western name, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. Shots were fired and the Second Sino-Japanese War officially began. Throughout August, Imperial Japan bombed Nanking, destroying much of the city and the Ginling campus. Of the foreign staff members, only Vautrin and her coworker Catherine Sutherland remained (Page 62). The bombing continued into the fall, and the college closed to students, but Vautrin remained to help the community as best she could: transporting the wounded to hospitals, helpingorphans, providing shelter and comfort to the community, and much more.

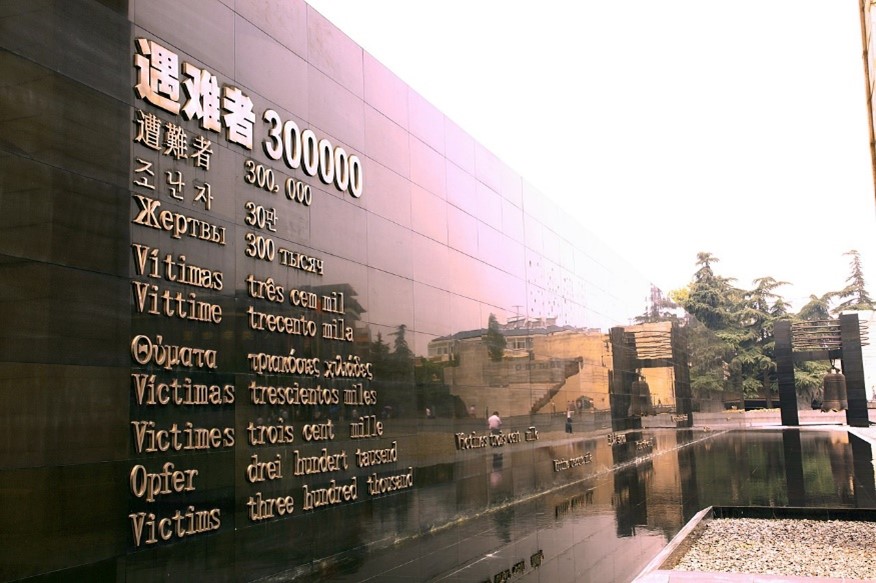

When Japan took Shanghai in August 1937, many soldiers and refugees retreated to Nanking, and the already struggling city provided medical aid. By December, most citizens had evacuated, and the Ginling college took in any women and children who were unable to leave. The Japanese allowed the college, the University of Nanking, and the nearby hospital to be a neutral zone during the occupation under the condition that Chinese soldiers did not seek refuge there (Page 71). The college put up American flags around the campus in hopes that it would deter the Japanese from attacking an American owned property, though it proved to be unsuccessful. The Japanese continued to invade the city: looting, murdering, and assaulting women and children. A study in the 1980s found that the total lives lost to the invasion was close to 340,000 (Page 82). The Japanese burned most of the city to the ground. Vautrin wrote in her diary about the flames all around the city, “light[ing] the night sky” and the smoke continuing during the day, writing “the fruits of war are death and destruction” (Page 82-83). She also wrote that previous residents would not recognize Nanking, describing it as “the saddest sight I ever hope to see. Buses and cars upset the street, dead bodies here and there, every house and shop looted and smashed if not burned” (Page 83). A doctor at the Nanking University Hospital also told of the assaults and callous killings of women and children by the Japanese soldiers in a letter to his family, “I could go on for pages telling the cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief” (Page 84).

Vautrin herself stood guard day and night against Japanese soldiers and usually her presence as a foreigner would deter them from entering, but on other occasions she would physically fight them off. A Chinese battalion commander wrote: “If she could not persuade them with words, she struggled with them by force. It was said that once she was slapped several times by the beastly soldiers” (Page 91). In mid-December, Japanese soldiers forced their way in to loot the college and look for Chinese soldiers and women. Vautrin ran around the campus trying to protect them. Most of the time, her presence and a letter from the Japanese Embassy stating the protection of refugees in the safe zone worked, but she was haunted by the times that was not enough (Page 95). She repeatedly wrote to the Japanese Embassy, begging them to keep the Japanese soldiers from entering the college, but the Embassy was apathetic, and the soldiers destroyed notices the Embassy sent. The safety zone lost their status on February 4, 1938, but it still was not safe for the refugees to return home (Page 107). Vautrin continued to watch over the 4,000 that remained, and the refugees named her “Goddess of Mercy” and “Living Goddess” (Page 123). On July 30, 1938, she was secretly awarded the Order of the Jade, the highest honor for foreigners by the Chinese Nationalist Government (Page 124).

When Imperial Japanese occupation was nearing its end, Vautrin began teaching a homecrafting program for practical skills in late 1938 (Page 116). Even with the 10,000 lives she saved, she still felt like she could have done more for the city. She had expressed suicidal thoughts both in her diary and to her coworkers. They begged her to take a year off and go home to her family, and she finally relented when she was promised the programs would continue (Page 133). Her doctor arranged for her to stay at the Psychopathic Hospital of the State University of Iowa for treatment. She returned to America with one of Ginling’s reverends and a teacher on May 14, 1940.

While Vautrin was in Iowa, her hometown of Secor was planning a celebration for her. They declared her birthday, April 12, Minnie Vautrin Day, and the presidents of ISNU and University of Illinois were expected to give speeches. No one was informed of how much she was struggling with her mental health. The celebration was postponed and eventually canceled (Page 138).

After she left the Iowa hospital, she begged to see her family in Michigan, but doctors and the Mission thought it was best if she first took a solo vacation at an Indiana State Park. She was then sent to her coworker’s home in Texas, where she tried to overdose on sleeping pills. Again, she asked to go to Michigan, but they sent her to Indiana to stay with another coworker, and they would prepare aid boxes to send to Nanking. The work gave her purpose, but she still felt inadequate for not being at Ginling. While staying at the apartment alone, she took her own life on May 14, 1941, at age 55. She left a note saying she felt she would never recover and that she felt like a failure (Page 144). Hu wrote that Vautrin always considered China her home and that “It was said that shortly before she died, she told her friends that if she could live twice, she would still want to serve the Chinese people” (Page 144). She is buried in Michigan with her family, and her gravestone has the four Chinese characters Gin Ling Yung Shen which translates to Ginling Forever.

Additional resources

Books:

American Goddess at the Rape of Nanking: the Courage of Minnie Vautrin by Hua-ling Hua

The Rape of Nanking: the Forgotten Holocaust of World War II by Iris Chang

Nanjing Requiem by Ha Jin

The Undaunted Women of Nanking: the Wartime Diaries of Minnie Vautrin and Tsen Shui-fang

Articles:

The Living Goddess of Mercy at the Rape of Nanking: Minnie Vautrin and the Ginling Refugee Camp in World War II (1937–1938)

American ‘Goddess of Mercy’ in the Nanjing Massacre: Minnie Vautrin and the Afterlife of Her Wartime Diary by Pingfan Zhang

Revisiting the Wound of a Nation: The “Good Nazi” John Rabe and the Nanking Massacre by Qinna Shen