From Abraham Lincoln’s first reference to the founding of Illinois State University to the demise of Old Main, historian Tom Emery explores this month in Illinois State University history.

May 7

One of the most iconic moments of NBA history happened on this date in 1989, as Chicago Bulls superstar Michael Jordan hit a floating jumper from the free throw circle in a deciding Game 5 of a first-round playoff series against Cleveland. The moment forever became known as “The Shot.”

The head coach of the Bulls was Doug Collins ’73, who is widely considered the best player in the history of Illinois State University men’s basketball.

Collins and Jordan first came together in 1986, just as Jordan was establishing himself as one of the greats of American pro sports history. Collins, the No. 1 overall pick in the 1973 NBA draft, had seen his career cut short by injuries in 1981, after eight seasons. He then was an assistant at both Penn and Arizona State before joining the CBS broadcast booth.

Jordan broke into the NBA in 1984 and was an immediate impact player. But the Bulls continued their string of mediocrity and were a combined 68-96 with a pair of first-round playoff exits in Jordan’s first two seasons in the league.

Though he had a thin coaching resume at the time, Collins was hired as Chicago’s head coach in May 1986. He was just 13 years removed from his on-court glory at Illinois State.

In Collins’ second season, the Bulls improved to 50-32, with the No. 3 seed in the Eastern Conference playoffs. In the postseason, the franchise advanced past the first round for the first time since 1981.

The 1988-89 edition of the Bulls were somewhat disappointing in the regular season, going 47-35 and finishing as the No. 6 seed for the playoffs. Their first-round opponent was Cleveland, which had set a then-franchise record for victories at 57-25. The teams had also met in the first round in 1988, but Cleveland won all six regular-season meetings in 1988-89.

Chicago proceeded to snap that streak with a 95-88 road win in Game 1, but Cleveland tied the series with a win in Game 2. The Bulls came back home and took Game 3 101-94 behind 44 points from Jordan, but the Cavaliers stayed alive with a 108-105 overtime victory in Game 4, overcoming a 50-point night from Jordan.

That forced a deciding Game 5 in Cleveland on Sunday afternoon, May 7, 1989. Like the rest of the series, the game was back-and-forth, with six lead changes in the final minute alone.

Chicago trailed 98-97 with six seconds remaining when Jordan nailed a clutch jumper for a one-point lead. A Cavaliers timeout followed before guard Craig Ehlo inbounded the ball, then received a pass and drove the lane for a layup with three seconds left and a 100-99 lead.

To no one’s surprise, Jordan got the ball at the end, fighting for the inbounds pass before gaining possession. He then headed crosscourt toward the free throw line and put up a hanging jumper over Ehlo at the buzzer. The shot was good, and Jordan soared toward the opposite sideline, pumping his fist as he was mobbed by teammates in a 101-100 Chicago win to end the series.

It was the first buzzer-beating shot to end a winner-take-all playoff game in NBA history, and it would not happen again until the 2019 postseason.

Though the moment is considered one of the most memorable in NBA history, Jordan’s legendary celebration was not shown in real-time on the CBS broadcast. Rather, the network showed Collins, running off the bench to join the celebration.

Chicago advanced to the conference finals in 1989, losing to eventual NBA champion Detroit. The Bulls then won three-straight NBA titles, a streak that ended with Jordan’s surprise retirement in October 1993. He returned late in the 1994-95 season, which sparked another run of three-straight world championships from 1996-98.

Collins, though, was there for none of them. Just weeks after “The Shot,” he was fired in the summer of 1989 by Chicago. Collins later served as head coach in Detroit from 1995-98.

In 2001, Collins returned to head coaching in Washington and was reunited with Jordan, who famously had come out of his second retirement. This time, the pairing was less successful, as the Wizards posted identical 37-45 records in 2001-02 and 2002-03, missing the playoffs each time. Jordan, who was an NBA All-Star in each of his two seasons in Washington, retired for the final time in 2003.

Collins later was the head coach of the Philadelphia 76ers from 2010-13, and he was named senior advisor of basketball operations in Chicago in 2017. In 2009, a statue of Collins and his head coach at Illinois State, Will Robinson, was unveiled on the campus.

May 15

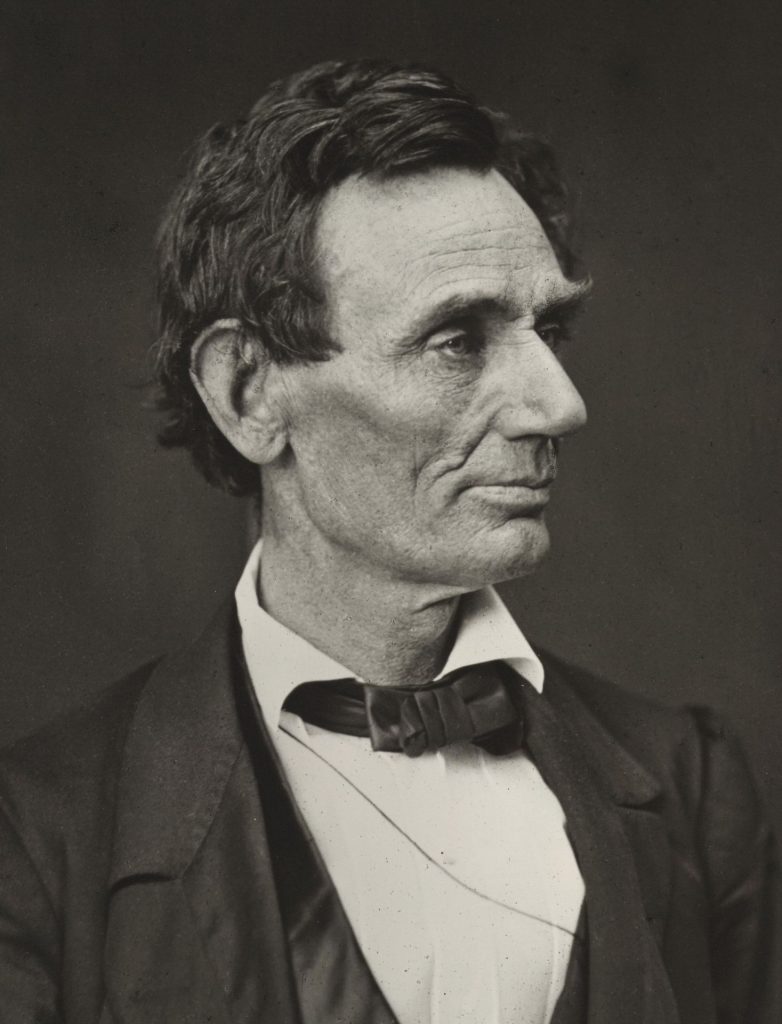

Today is the anniversary of the first known reference to Abraham Lincoln of his role in the founding of Illinois State University. The reference, on May 15, 1857, was part of Lincoln’s most lasting contribution to the history of Illinois State—that the University would be located in present-day Bloomington-Normal.

Of Lincoln’s many connections to Illinois State, none are more significant than his role in helping with the financial documents, enabling the University and securing it for Bloomington.

When Illinois State was founded in early 1857, four Illinois cities bid for the right to host the campus—Bloomington, Peoria, Washington, and Batavia. The top-two contenders, however, were Bloomington and Peoria, and both cities jockeyed for the privilege of having Illinois’ first public institution of higher learning.

In 1907, university President David Felmley succinctly wrote that “several prominent residents of McLean County,” such as business powerhouse Jesse Fell, “were determined to have the school located near Bloomington.” To make that happen, though, required money—and plenty of it.

McLean County raised $50,000 from the sale of lands, while Fell went to work. With his usual indomitable spirit, he persuaded area residents to pledge money and land to strengthen Bloomington’s proposal to the state Board of Education. Initially, Fell raised some $50,000 in individual subscriptions.

Fell even engaged in some cloak-and-dagger activity, sending a spy to Peoria “to ascertain, if possible, what that county was going to bid.” The clandestine information revealed that Peoria might outbid McLean County.

As a result, Fell and his subscribers increased their proposal to $71,000, while the county added another $20,000. With subscriptions from the county and individuals, the entire Bloomington proposal was $141,000.

At a meeting on May 7, the Board of Education examined the proposals. Washington and Batavia were not competitive, while Peoria’s total bid came in at $80,032. That was much less than the offer of Bloomington, which was given the university.

That honor, however, came with a hitch. Charles Hovey, who would become the University’s first president, preferred that the University should be located in Peoria. He presented an amendment, adopted by the board, that required the Bloomington proposal to be guaranteed within 60 days. If not, the location of the University would move to Peoria.

The requirement was particularly applicable to the McLean County portion of the Bloomington bid. There was no certainty that the county commissioners would honor the request, and if county government should change, any future commissioners might renege on the deal.

Lincoln would ultimately handle many of the tasks to prevent any default, including the drafting of a guaranty to support McLean County’s bid. Meanwhile, Fell and his friends again went to work, pledging money to ensure the guaranty of the county’s subscription.

On May 15, the Executive Committee of the Board of Education met in Bloomington, as the reports stated, to “discharge the responsible duties assigned to them” and “secured, by a guarantee, the McLean County subscription.”

This action was “according to a bond drawn by A. Lincoln, Esq., of Springfield, who acted as counsel for the committee.” This mention of Lincoln is the first to the future president in the official minutes of either the Board of Education or the Executive Committee.

The guaranty was critical to keeping the campus in Bloomington. Had the guaranty not been prepared, signed, and presented in a timely manner, the University would likely have been awarded to Peoria. Lincoln’s pivotal role in the founding of Illinois State Normal is indisputable.

That significance is echoed in an 1879 history of McLean County, which declared that the guaranty “was of great value at the time, and is one of the important steps taken to secure the Normal University” not only for its mere existence, but also for the city of Bloomington. Indeed, Lincoln’s actions in the spring of 1857 shaped the course not only of the University, but the city itself.

May 17

On this date in 1975, Illinois State held its annual commencement. Among those receiving degrees was Dr. Jenny Pan-Yun Ting ’75, who earned a bachelor’s in medical technology. Ting is now one of the nation’s most accomplished microbiologists.

For the last 40 years, Ting has been on the faculty of the University of North Carolina, where she has published dozens of studies on genetics, microbiology, cancer research, infectious diseases, inflammation, and vaccines.

A native of Taiwan, she came to the United States after receiving a foreign student scholarship from Illinois State. She then earned her doctorate from Northwestern University before post-doctoral research appointments at the University of Southern California and Duke University.

In 1984, Ting was named assistant professor at North Carolina, ascending to associate professor in 1990 and full professor in 1993. She was named the Kenan Professor in 2009.

Ting has headed the immunology program at the university’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center since 1991. In 2008, she was named director of Lineberger’s Center for Translational Immunology, as well as co-director of the Institute of Inflammatory Diseases.

In 2015 and 2016, she was named a Thomas Reuter Highly Cited Researcher, followed by honors as a Clarivate / Analytics Highly Cited Researcher in both 2017 and 2018. She was named a Highly Cited Researcher of the Web of Science, Clarivate Analytics, a recognition given to the top 1% in the field, each year from 2020-23.

Ting was the vice president of the American Association of Immunologists in 2019-20, and served as the organization’s president in 2020-21. She was the first woman of color to serve as the association’s president.

In addition, Ting earned the NCI Outstanding Investigator Award each year from 2016-19, and received the Hyman L. Battle Distinguished Cancer Research Award in 2017. In 2013, she was the recipient of the University Award for the Advancement of Women at North Carolina.

In 2022, Ting was elected as a member of both the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Her remarkable skills as a researcher are also seen in the myriad of editorial boards she has served on, including the Journal of Immunology, Molecular and Cellular Biology, and the Annual Review of Immunology.

In 2010, Ting was inducted into the Illinois State University College of Applied Science and Technology Hall of Fame.

May 22

On this date in 1946, the bell tower was removed from “Old Main,” the original campus building of Illinois State.

The removal of the tower was, in many ways, the beginning of the end of Old Main, which had served the campus since 1860. The venerable building, an anchor of the campus for generations of ISU students, was finally demolished in the summer of 1958.

For decades, Old Main had been the sole campus building at Illinois State. The three-story structure was topped by a striking bell tower, whose tones had become a signature of daily life at Illinois State. The cornerstone of Old Main had been laid on September 29, 1857, and the building was first used at the inaugural commencement in university history, on June 29, 1860.

But even then, there were concerns about the building’s design. Charles Hovey, the first president of Illinois State, took issue with the architectural plans of “Old Main,” especially the placing of the bell tower which, he said, “had nothing to roost on.” Hovey labeled the difficulties with the architectural design as “blunders” and blamed the Board of Trustees for its desire to “conform to local humor, prejudice, or taste.”

Hovey’s words may have been haughty, but they were proven accurate decades later, as the University struggled with the physical integrity of the beloved old building. As the campus grew, Old Main remained the centerpiece; one source wrote that “other buildings came to dot the campus, clustering around the original building like chicks about a hen.”

However, the bell tower continued to deteriorate and by 1932, it was actually leaning to one side. As a result, steel beams were installed for support from the basement to the attic. The improvements, though, proved inadequate, and in the postwar years, the structural deficiencies of Old Main had reached alarming levels.

The problems reached a head in a sudden development on February 21, 1946 when longtime ISU President Raymond Fairchild, who was on his way to Cleveland for a speaking appearance at the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, was called to Springfield. There, he was summoned to a briefing by the Division of Architecture and Engineering, which reported that Old Main was unsafe.

That afternoon, Fairchild appeared before the faculty at Capen Auditorium to deliver the news. University historian Helen Marshall writes that a shaken Fairchild stood “tall and pale, his voice somewhat affected by the gravity of the occasion.”

An evacuation of the 24 classrooms of the second and third floors of Old Main was ordered within 48 hours. Students were informed at an assembly on February 22. By February 25, Marshall writes that “there were padlocked gates on all stairs leading up from the first floor.”

The move created an emergency need for space. Classes and offices were shuttled around the remaining campus facilities, as well as churches and other landmarks in the city.

Still, there was a bright spot that reflected the University’s academic strength. On April 27, the Vidette’s news story “Old Main Unsafe and Classes Removed” from the February 27 edition earned first place as best news story at the Illinois College Press Association.

The impending doom of Old Main became obvious to everyone, particularly as protective fencing was erected around the building. University administration made the decision to remove the bell tower and the third floor, keeping the lower two floors intact. A flat roof was planned, replacing the sloping roof that had defined the building since its inception.

At the time, many feared that the building would soon be demolished. The senior class of 1946 was especially concerned, as a longtime commencement tradition was the walk-through of Old Main by the graduating class to close the ceremony. An editorial in the Vidette lamented that “students will not walk [the] last mile from Old Main.”

On May 22, 1946, the bell tower was removed from Old Main. Students and faculty gathered to watch the removal, which signified the loss of a signature piece of the University’s history. The removal is remembered as one of the sentimental moments in the story of Illinois State.

The sight of the revamped Old Main, missing a story and with a mundane roof, was startling to the campus community. The August 1946 edition of the Alumni Quarterly sadly wrote Old Main was “flat-roofed and with only two stories…no longer towers over the campus…it’s the size and shape of a barracks.”

There were loud calls to restore the building, and the bell tower, among the alumni base. On June 17, 1946, a letter to the Bloomington Pantagraph related the “indignation and dismay upon seeing the disappearance of the tower on Old Main…a desecration of a venerable and beautiful building.”

A 1900 graduate also wrote of “the shock I got when I drove through the Normal campus a few days ago and saw the Old Main building…Normal can never be what it was without this old landmark.”

Discussions of a replica of Old Main, possibly five stories high, were also considered. But the difficult decision to raze the building was finally made. The demolition began on June 17, 1958, another emotional moment for the campus community.

The sweeping impact of Old Main and its tower on everyday life at Illinois State was captured in the July 10, 1946, edition of the Vidette, which reported that ISU students “have been surprised at their dependence on the bell for setting their watches and getting to class on time.”

The bell itself was placed in a memorial on the north end of the Quad in 1955 to honor Old Main, an anchor for thousands of Illinois State students, a legacy that lingers on the campus today.

Tom Emery is a freelance writer and historical researcher who, in collaboration with Carl Kasten ’66, co-authored the 2020 book Abraham Lincoln and the Heritage of Illinois State University.