William Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors opens with an ultimatum that seems out of place for what is supposed to be a comedic romp. Egeon, an elderly merchant from Syracuse, is sentenced to death for entering Ephesus despite a decree barring travel between the two cities. Hearing Egeon’s sad tale about his separated family, however, the Duke offers a lifeline: If Egeon can find someone to pay his fine by the end of the day, his sentence will be lifted.

With that opening, the play effectively starts a timer that will run out in the last scene. Apparently, Shakespeare wanted his audience to keep that in mind, as the characters keep mentioning the hour. In act one, scene two, Dromio of Ephesus notes that “The clock hath strucken twelve upon the bell” (1.2.45), worried that his master, Antipholus of Ephesus, is not home for lunch with his wife. Said wife, Adriana, begins act two, scene one by announcing that it is now 2 o’clock, and her husband is nowhere to be seen. In the final act, right before Egeon is brought back onstage for his execution, a bystander happens to glance at a clock, observing that “the dial points at five” (5.1.122). These clues tell us that the entire play occurs in a little over five hours—roughly from lunchtime to dusk.

During Shakespeare’s time, there was an established convention in playwriting called the “unity of time.” Although definitions vary, the basic idea is that the action of a play should fit within the span of a day. Some defined that as 24 hours, while others argued that it should be 12, since characters need to sleep, too. The strictest interpretations limited the action to the actual time it takes to perform the play or as close to it as possible: A handful of hours from the first scene to the last. Adherents to the unity of time pointed to a line in Aristotle’s Poetics for justification, although the ancient Greek philosopher and theatre scholar never explained why this should be the case, or even whether it was meant to be a firm rule.

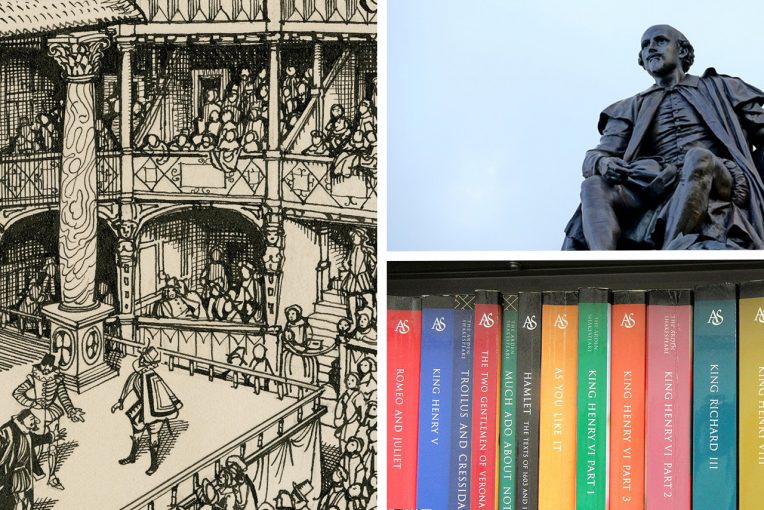

Nevertheless, the “unity of time” became an important principle in some parts of Europe, especially Italy, during the Renaissance. It was actually one of three unities, the others being the “unity of place” (a play should take place in a single location, or close enough that a character could plausibly travel there within a day) and the “unity of action” (a play should have one coherent story, ideally with one protagonist). Later, in 17th century France, the government enforced the three unities so that neglecting them could land a playwright in hot water. English playwrights, on the other hand, were less concerned with these rules, although some, like Shakespeare’s friend and rival Ben Jonson, used them to give their plays an air of continental sophistication. In general, Shakespeare did not bother with the unities. Wars are fought and won within the span of a single act in many of his tragedies and histories, and characters sail across the Mediterranean or from England to Italy and back in Othello, The Merchant of Venice, Pericles, and Cymbeline, just to give a few examples. In The Winter’s Tale, the allegorical figure of Time appears halfway through the play to simply tell the audience that we are now jumping sixteen years. Shakespeare clearly was not interested in fitting his dramas into a predefined timespan.

But in a few of his plays, Shakespeare decided to follow the unity of time. Aside from The Comedy of Errors, The Tempest also takes place in an afternoon. In act 1, scene 2, Prospero asks the spirit Ariel what time it is. Ariel answers, “Past the mid season,” which means past noon. Prospero is even more specific, almost as if he is synchronizing some invisible clock with his servant: “At least two glasses. The time ‘twist six and now / Must by us both be spent most preciously” (1.2.284-286). Prospero reveals that it is about 2 p.m. in the first act, and that his plans will come to fruition by 6 p.m. In other words, the entire story takes place in about four hours.

Why does Shakespeare focus so much on time in these plays when he does not seem to care at all in others? What effect does following the unity of time have? Early modern proponents argued that the unity of time was necessary for the performance to be believable. But that is not a satisfying answer since we must suspend our disbelief in the theatre anyway. Who cares whether the span of the drama fits our own experience of time passing when we are talking about a comedy with two sets of identical twins who happen to have the same names despite being separated when they were babies? Instead, it might be helpful to find an analogy in sports movies, where the action builds up to an important final match. This contained plot structure has a clearly defined endpoint, even if it is further away than a day. This kind of storytelling pushes the action forward and puts pressure on the characters to solve problems quickly or improvise, forcing them to take actions they would not have if there was more time. Knowing there is a deadline on the horizon also adds suspense and a sense of urgency for the audience. Will they be ready in time? So, while the unity of time may seem like an arbitrary rule that limits creative freedom, there may be a good reason to consider it. And perhaps that is why Shakespeare used it in some of his plays.

But also, a limited timeframe is a reality for any theatre artist since the audience will not sit in the theatre for hours on end. Playwrights have to be efficient storytellers. Based on journals and other accounts from the period, historians believe that performances in Shakespeare’s time started around 2 p.m. or 3 p.m. and lasted until about 6 p.m. before it became too dark. Of course, the theatre industry was not standardized and most people did not have clocks, so these times probably varied from case to case. There were also opening acts, such as music, dancing, acrobatics and clowning, before the actual play started, as well as a jig (a song and dance routine) afterwards. So, the actual play would have taken around two to three hours to perform, which is in line with most Shakespeare productions today. Interestingly, this performance time roughly corresponds to the timeframes mentioned in The Comedy of Errors and The Tempest, beginning in the early afternoon and ending by 5 p.m. or 6 p.m. Perhaps Shakespeare was thinking about actual time passing in the Globe when he added those references to the time of day.

It is not only Shakespeare who has to work with time constraints. ISF Artistic Director John Stark asks the directors each season to limit their productions to two and a half hours. Some of Shakespeare’s longer plays (Hamlet being the longest) have to be cut to meet this requirement. Luckily, The Comedy of Errors and The Tempest are among Shakespeare’s shortest plays, so the directors have more breathing space, although they may choose to trim some lines to keep the play moving. And just as Shakespeare’s audience may have been thinking about the actual time of day when characters talk about finishing things by 5 o’clock or 6 o’clock, you are always conscious of time passing in ISF’s outdoor theatre at the Ewing Cultural Center. Even if you never check your watch or phone during the show, the sun sets roughly around intermission each evening. Like clockwork, you see the moon and stars, and feel the air cool down. Even if days or weeks or months go by in the story, we are all experiencing “one revolution of the sun,” as Aristotle said in The Poetics, together.

Think about how these different dimensions of time align when you see The Comedy of Errors and The Tempest this summer!