Twelfth Night is considered one of Shakespeare’s most musical plays, with Feste the fool singing many songs throughout the play. For the Illinois Shakespeare Festival’s 2024 production, ISF alum Jordan Coughtry will compose and perform original music inspired by the lyrics included in the text, in addition to performing the role of Feste. This is not the first time that Coughtry is collaborating with director Robert Quinlan to support Shakespeare’s drama with music; in ISF’s 2019 production of As You Like It, Coughtry played a sweet-voiced, ukelele-strumming Touchstone, yet another one of Shakespeare’s jolly fools. But what did music sound like in Shakespeare’s own time? And did Shakespeare actually write the lyrics in his plays?

Many of Shakespeare’s plays include stage directions that indicate music or dancing. For example, the masquerade ball in the first act of Romeo and Juliet shows how music is sometimes integral to the storytelling, as Romeo and Juliet’s shared sonnet emerges out of a dance. The sheep-shearing festival in Act 4 of The Winter’s Tale also relies on music to create the festive atmosphere of Bohemia, which draws a sharp contrast to gloomy Sicilia. The Winter’s Tale also calls for music to underscore the miracle of Hermione’s “resurrection” in Paulina’s line: “Music, awake her! Strike!” (5.3.124) Likewise, Prospero and Ariel’s magical powers in The Tempest operate through music, as the stage directions mark the presence of music almost every time a spell is cast.

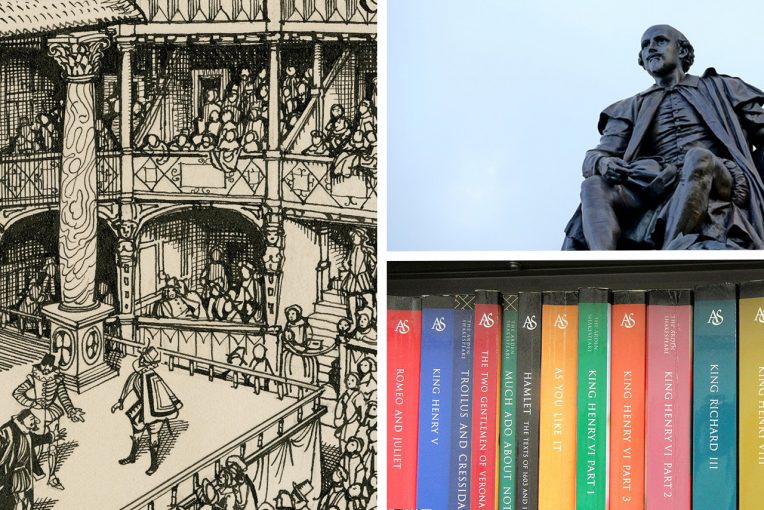

In The Tempest, Ariel talks about beating their tabor, which is a small drum, while ensnaring Caliban and his co-conspirators with magic. This instrument is mentioned numerous times in Shakespeare’s plays, including in Twelfth Night where Feste enters a scene playing one. Other instruments that often come up include trumpets and drums (especially fitting for plays with battle scenes), pipes (among other wind instruments), viols (a distant cousin of the modern violin), and lutes (which one could play while singing). Historians believe that the King’s Men would have chosen different styles of music for the more rambunctious, open-air Globe theatre and the acoustically focused, indoor Blackfriars. The latter catered to a more elite audience that would have favored strings, wind instruments, and softer singing. Conversely, performances in the outdoor theatre would usually be followed by dance entertainment called a jig, which would require lively, more rhythmic music.

With this in mind, let us turn to Twelfth Night and see how music is omnipresent in this play. Duke Orsino’s first line is a statement on music: “If music be the food of love, play on” (1.1.1). Aside from establishing a thematic connection between music and romance, the line also tells us that the play must begin with music. A few lines later, Orsino says, “That strain again!” (1.1.4) This means he wants to hear a particularly beautiful phrase again and orders the musicians to replay it. In Shakespeare’s time, hired musicians usually sat in the balcony directly overlooking the stage in full view of the audience (as opposed to our modern convention of hiding musicians in the orchestra pit). Having Orsino address the musicians directly at the start of the play would have made them even more noticeable.

Orsino is a lover of music, but he himself does not sing or play an instrument in the play. It was more common for people of lesser rank, such as fools and pages, to sing for their masters. We see examples of both in Twelfth Night. Feste performs five of the six songs with lyrics in the play in various contexts, from drunken revelry and performing for the Duke for money, to singing directly to the audience as a kind of epilogue to the play. One must be a talented musician to be a Shakespearean Fool, it seems, if we consider Feste alongside other musical jesters such as Touchstone and the Fool in King Lear. Pages and other young servants are also often responsible for music in Shakespeare’s plays. Brutus’ servant Lucius in Julius Caesar, who plays music to help his master calm his nerves during a war, and Balthasar sings “Hey, nonny, nonny” for the Prince and his entourage in Much Ado about Nothing. In Twelfth Night, Viola relies on her musical abilities to gain employment from Orsino: “for I can sing / And speak to him in many sorts of music / That will allow me very worth his service” (1.2.60). Viola’s voice, which Orsino favors, is even likened to a musical instrument: “thy small pipe / Is as the maiden’s organ, shrill and sound” (1.4.35). The line is ironically funny because Orsino is commenting on the feminine timbre of Viola’s voice without realizing it. But at the same time, it reminds us that female characters often sing to great dramatic effect in Shakespeare’s plays, such as Desdemona’s “Sing, willow, willow, willow” in Othello or Ophelia’s “And will he not come again?” in Hamlet.

It is unclear whether Shakespeare wrote the lyrics in his plays. The earliest record of “The Willow Song,” for example, predates Othello, although they are notably different from Desdamona’s version. Although they sometimes touch on themes and sentiments expressed elsewhere in the play, most song lyrics in Shakespeare’s plays do not reference specific plot points or characters. A few exceptions include “Fear No More the Heat of the Sun” in Cymbeline, sung at an impromptu funeral (although the person sung to only appears to be dead) and “Full Fathom Five Thy Father Lies” in The Tempest, sung by Ariel to make Ferdinand believe his father is (again, falsely) dead. But most lyrics are disconnected from the rest of the play, suggesting that the song was added later. Some songs have been identified as popular ballads from the period, also appearing in other plays or published collections of songs.

Perhaps because it is likely that they are not Shakespeare’s, the actual words to many of the songs are often overlooked. And maybe it is true that these songs were slotted in later, interchangeable with other ballads of the time and thus not an integral part of the story. But whatever the case may be, it is clear that Shakespeare thought a lot about music in Twelfth Night, which begins and ends with music. Moreover, Shakespeare must have believed that music was a crucial part of the theatre-going experience, which explains why he wrote in countless occasions for the actors or hired musicians to play music throughout his plays. And questions of authorship aside, the lyrics included in published versions of Shakespeare’s plays have inspired many composers—such as Jordan Coughtry, whose original music you will hear this summer.

In place of a conclusion, here are the lyrics to Feste’s final song in Twelfth Night, sung after all the characters have exited the stage. The final verse, which announces that “our play is done,” suggests that this song may have been written by Shakespeare or at least adapted to serve as the epilogue. In a mere 20 lines, Feste runs through the span of a human life, affirming the struggle of living against the incessant turmoil of “the wind and the rain,” which in the context of the play could also symbolize loss and heartbreak. It is a strangely moving declaration of perseverance and resilience. It is also a promise to the audience that “we’ll strive to please you every day,” a promise that Shakespeare’s play has kept for over four hundred years. Come to Twelfth Night at the Illinois Shakespeare Festival to hear Coughtry’s musical rendition of these beautiful lyrics.

When that I was and a little tiny boy,

(Twelfth Night, 5.1.412-431)

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

A foolish thing was but a toy,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came to man’s estate,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

’Gainst knaves and thieves men shut their gate,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came, alas, to wive,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

By swaggering could I never thrive,

For the rain it raineth every day.

But when I came unto my beds,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

With tosspots still had drunken heads,

For the rain it raineth every day.

A great while ago the world begun,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

But that’s all one, our play is done,

And we’ll strive to please you every day.