From a fierce Civil War battle that tested the 33rd Illinois “Teacher’s Regiment” to the University’s reaction to Apollo 11 landing on the moon, historian Tom Emery explores this month in Illinois State University history.

July 7

On this date in 1862, Illinois State students were heavily involved in the Civil War battle of Cache River, Arkansas, as part of the 33rd Illinois, which was forever known as the “Teacher’s Regiment.”

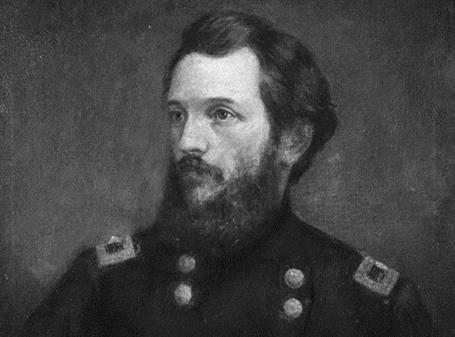

The first colonel of the 33rd was Charles Hovey, the founding president of Illinois State, who distinguished himself for bravery and valor in the battle.

Clearly, the men of the 33rd were not just bookworms; they were hardened fighters. Their toughness was on display in the fight at Cache River as Confederates looked to slow the Union Army of the Southwest in their advance on eastern Arkansas.

Hovey led a brigade that included the 33rd across the river when two Texas cavalry regiments tried to stop the crossing. Thus began the small, but spirited, battle of Cache River, which is also known by several other names, including Cotton Plant, Hill’s Plantation, and Round Hill.

The Federals were initially overrun, but Hovey stabilized the situation quickly. In 1993, Trans-Mississippi theater historian William Shea wrote that “in a moment of inspiration, Hovey dismounted and picked up a rifle and cartridge box from a wounded soldier. He walked forward a few yards, found an unoccupied tree, and methodically began to load and fire in the general direction of the enemy.”

Hovey managed to fire two or three rounds before he was struck in the chest by a spent bullet. His sturdy nature, however, came through. Shea wrote that Hovey “picked up the bullet and shouted above the din that the rebellion ‘did not seem to have much force in it.’”

Shea summarized that “the colonel’s bravura performance had an ‘electric effect’ on the men around him.”

Civil War battlefields were no place for the faint of heart, even in smaller battles like Cache River. One officer of the 33rd wrote that “a few feet above our heads the trees were almost swept clean” by flying bullets. He continued that “leaves and twigs and limbs severed from the trees by the leaden storm dropped upon us like hail.”

Hovey later halted a retreat from his troops by dramatically jumping a fence on his horse with a sword in hand, screaming, “Lord Almighty God, boys! Are you going to run like sheep?” Shea declared that, “for the second time in an hour, the former college president saved the day.” Hovey would later ascend to brigadier general.

In one instance, Sgt. Harvey Dutton, a Normal student in Company A, was threatened by a rebel horseman. Dutton had just fired his musket, and was largely helpless; in that era, most weaponry was single-shot, and even the best soldiers could reload only three times a minute.

Dutton had no way out, and didn’t even try. Rather, he reached for a revolver from his belt and dropped the enemy horseman. Dutton survived the war and lived to a ripe old age, dying in 1928 at the age of 92.

The tide of the battle soon switched from retreat to advance, which carried the fight for the Union. Shea reports that the Illinoisans “loosed a smashing volley at point-blank range against the flank of the Confederate column. The ‘storm of lead’ practically annihilated the leading elements of the 12th Texas Cavalry, ‘tumbling horse and rider indiscriminately over each other.’” Hovey proudly wrote “they left as suddenly as they came and in great disorder.”

That largely ended the battle, but one Normal University man, Edward Pike of Company A, earned the highest recognition of all.

Pike displayed his devotion at Cache River as he prevented a cannon from falling into enemy hands amid a galling fire. Though the gun weighed 2,000 pounds, the slender Pike began dragging the piece to the rear as another man of Company A, Chauncey Chamberlain, stepped forward to help amid pistol and shotgun fire from enemy Texans.

Shea’s 1993 account marvels that the fire “somehow failed to hit either man” before the rest of Company A fought back and repulsed the rebels with “a flurry of rifle fire. Making the most of this brief respite, Pike and Chamberlain manhandled the cannon out of the enemy’s grasp and attached it to the limber” before it was hauled to safety.

Though he was unharmed, Pike’s cap was pierced by a bullet during the struggle. His valor earned him the Medal of Honor, the highest decoration for military service.

July 15

On this date in 1936, the high temperature in Bloomington-Normal reached 114 degrees, the warmest ever recorded in the Twin Cities. Like everyone else in the area, Illinois State students were sweltering.

Illinois and much of the Midwest endured unseasonably hot summers for much of the 1930s. Nothing, though, was as brutal as the summer of 1936, when much of the nation was trapped in overpowering heat as Americans struggled to recover from the Depression.

At least 13 states from New Jersey to Louisiana recorded their warmest-ever temperatures during the summer of 1936. An estimated 4,500 to 5,000 deaths nationwide were attributed to the heat that year.

In Illinois, Peoria residents suffered through 23 days of 100 or better that summer, while Springfield reached 100 degrees on 29 days that summer. Highs in the capital city never dipped below 100 from August 12-28—a span of 17 days.

Fifty people died from heat-related causes in Springfield in 1936. To the north in Moline, the mercury hit 100 or above for 11-straight days from July 5-15.

In that same span, high temperatures in Bloomington-Normal reached at least 106 degrees. Five of the six hottest days on record in the Twin Cities occurred consecutively from July 11-15, 1936. The highs, respectively, in that stretch were 109, 110, 109, 111, and 114 degrees.

Like everyone else, Illinois State students were hammered by the hot temperatures. On July 16, the university physician told the Vidette that “the heat wave is the chief cause of the most of our present illnesses” on campus. She reported “an increased number of cases of fainting,” adding that “boils, and skin and ear infections are prevalent, all of which are probably caused by bathing in impure pools.”

Sunburn, however, was not a problem. The doctor attributed that “to the fact that the extreme heat drives the students to the shadiest places available.”

Finding that shade was a problem, as ISU students scrambled to find anywhere that offered some relief. On July 30, the Vidette reported that the fire escape in the rear of Fell Hall was “much used as a heat escape” by students who wanted “a shady vantage point from which to woo any transient breeze that may chance that way.” In that same issue, the paper lamented heat so severe that it “would not let one sleep.”

The intramural programs for the summer school term were hit particularly hard, as many students dropped out or didn’t show up. On July 9, the Vidette reported that “forfeit games mar [the] third week of intramural play.” No games in IM volleyball were played that week “because of the tropical temperature of the gym.”

A week later, the paper followed up that “the intense heat…seems to have put a crimp in the more active sports of the intramural program. Most of the games this last week were won on forfeits.” Still, at least 40% of male students participated in the IMs. The director stated that “when one considers the extreme heat of most of the term, this [was] a commendable turnout.”

Later generations of ISU students were able to take advantage of an invention that their peers would have craved in 1936: air conditioning. But the unfortunate souls who sweltered on campus, and around the nation, in 1936 had little respite in one of the worst summers on record in American history.

July 20

On this date in 1969, Apollo 11 landed on the moon. With an estimated 650 million watching worldwide, including many at Illinois State, the lunar module landed at 3:17 p.m. Normal time on July 20.

Neil Armstrong finally stepped out of the module at 9:39 p.m., and made his famous first step at 9:56 p.m. He was followed by fellow crew member Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin 19 minutes later. They were the first of 12 men, all Americans, to walk on the lunar surface between 1969-72.

Aldrin and Armstrong were on the moon for a total of 21 hours, 36 minutes, with 2 hours, 31 minutes spent outside the lunar module.

The Vidette recognized the achievement of the first lunar landing on July 23, 1969, with a headline comprised of the simple, yet respectful, words “Congratulations Apollo 11 Astronauts.”

In his column in that issue, Ed Pyne, who went on to a long career in local journalism, called the landing “the greatest day” as Armstrong and Aldrin “joyously bounced up and down on the moon’s surface,” sending back “unbelievably fabulous pictures.”

One of the moon rocks that Armstrong and Aldrin collected on the lunar surface was later displayed at Illinois State. The stone, which was loaned from a NASA station in Cleveland, was the highlight of a three-day “re-opening” event at the Funk Gem and Mineral Museum in Cook Hall on April 27-29, 1973.

As expected, security for the moon rock was tight. The Vidette reported that the stone “will be under an official guard while it is on campus.”

ISU students and faculty had watched the space race with keen interest throughout the decade, with a mixture of awe, inspiration, and fear. That was certainly the case in the Vidette edition of May 10, 1961, which was published five days after Alan Shepard had become the first astronaut in space.

In a 15-minute flight, Shepard and Mercury-Redstone 3 were shot straight up into space in an effort to keep up with the Soviets, who had been the first to orbit the Earth the previous month.

The Vidette was inspired by Shepard’s feat, imploring fellow Americans to say, “Yes, we did it! We couldn’t be happier.” The paper, though, feared that the United States would lose the space race, noting that the accomplishment “means very little compared to [the Soviets’] around the world orbit.”

“This is just the beginning for us,” concluded the Vidette, though the concern was evident. “America must rise yet further. She will not fail; she cannot fail.”

On February 20, 1962, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, circling three times. The accomplishment had personal meaning for Dr. Eric Smithner, an associate professor of foreign languages at ISU, who had been a classmate of Glenn at Muskingum College in Ohio.

The Vidette reported that Smithner “remembers John Glenn as a red-haired, freckle-faced kid whom the girls thought of as cute.”

That May 1, the Vidette used Glenn’s feat to call on everyday improvements back on Earth. “It seems ridiculous,” wrote the paper, “that John Glenn can circle the Earth three times … yet thousands of Americans cannot travel more than a few miles on our highways without being killed in the process.” The paper backed up its statement with some eye-opening statistics on the number of passenger and pedestrian deaths in the U.S.

On March 14, 1966, ISU space buffs could enjoy a lecture at Bloomington Senior High School from Dr. Leonard Reiffel, who directed a program for NASA’s Lunar and Planetary Programs Office. His topic was “Our Space Program: How Valid?”

On April 10, 1970, the Vidette printed a wire report on Apollo 13, “a rundown of America’s third moon landing in nine months.” Apollo 13, though, never reached the lunar surface after an explosion that threatened the lives of the astronauts on board, and gripped Americans with fear that the three men may not return.

One of the Apollo 13 astronauts, James Lovell, later had Illinois State on his mind, at least indirectly. In early 1972, the Illinois Board of Higher Education called for the cut of all mandatory physical education requirements at six state universities, including ISU.

Lovell, then-head of the President’s Council on Fitness, joined Governor Richard Ogilvie, the American Medical Association, and various presidents and deans in penning a letter to President Richard Nixon condemning the actions of the ISBE.

Illinois State continued its fascination of the space race right into the final two lunar missions, Apollo 16 and Apollo 17. On April 27, 1972, the words “Apollo 16 splashes down today” were found next to the masthead of the Vidette.

That December 13, the Vidette covered Apollo 17 under the headline “Apollo explorers enjoy lunar scene.” Back on Earth, the ISU community, watching the video feeds, enjoyed it themselves, as they had throughout all six American lunar landings.

Tom Emery is a freelance writer and historical researcher who, in collaboration with Carl Kasten ’66, co-authored the 2020 book Abraham Lincoln and the Heritage of Illinois State University. Watch for another feature by Emery later this month focused on Redbirds who made Olympic history.