Children of color continue to be treated differently in the public school system, resulting in a “school-to-prison pipeline” for many underrepresented students, according to Assistant Professor of Special Education April Mustian.

“This pipeline is disproportionately funneling children of color out of public schools and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems,” said Mustian, who noted statistics show that black students are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students, and are four times more likely than white students to receive office referrals in middle school. Additionally, Latino students are almost five times more likely than their white peers to receive a suspension for a minor infraction.

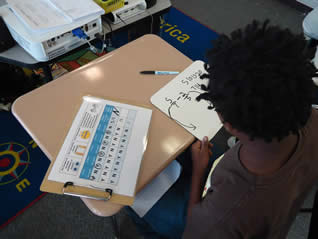

Mustian explained these statistics show many students of color, especially black males, are being singled out in disciplinary practices when the same or more problematic behavior of a white student is less likely to result in as severe a consequence. Such disciplinary practices have been a linked contributor to the misidentification of black male students in special education under the category of emotional disturbance.

“Teachers need to begin looking at contextual factors that affect behavior,” she said. “Many teachers’ implicit biases impact how they discipline and identify students because there is often a cultural mismatch.”

Mustian has begun working with a school district in Illinois collecting data on student discipline practices and how they specifically impact students of color. “Over the next year, I will work with the district on professional development for staff on how to promote positive, prosocial behaviors and become more culturally responsive in their behavior management practices,” she explained.

The professional development will be modeled after a framework called Double Check that comes from Johns Hopkins University and is being implemented in several states. This builds on school-wide positive behavior support systems to help teachers enhance five core components of culturally responsive practices.

Those components, known as CARES, are a connection to the curriculum, authentic relationships, reflective thinking, effective communication and sensitivity to students’ culture. “The professional development would be a combination of training – such as workshop models – and coaching with follow-up supports. These are critical to implementing and sustaining effective teaching practices over time,” said Mustian.

She explained this research will be several years in the making. “Once the professional development practices have been implemented, I hope to collect more disciplinary and special education data to see if the practices are working to decrease the number of students of color who are being referred, suspended, expelled and identified in special education,” she said.

As a special education professor, Mustian said she continually challenges her students not to be colorblind but, instead, embrace diversity in the classroom and view it as strength on which to foster strong relationships. “I want my future teachers to ask themselves ‘why is the student acting this way’ and to do so while using a culturally responsive lens,” she said. “I hope we can eventually see national changes in the way we support students of color and students of color who have disabilities. The system has historically failed them.”