Glass artist Dean Allison sees a lot in a human face. He sees what has been trapped on the skin. He sees the person’s facial expression, wrinkles, and pores. He sees a life lived as he attempts to capture a moment.

When he creates a portrait, Allison covers his subjects’ faces—and sometimes their entire upper body—in rubber. He makes a mold and manipulates the wax, adding and subtracting material to reveal a person’s essence, until he arrives at an image in time. He fills the mold with molten glass, leaving a frozen impression of his subject that will last long after the artist and subject are gone.

Appears In

“One of my favorite painters was Francis Bacon, and one of the things he said was, ‘My paintings are a snapshot in time.’ And I like to think of my work like that,” said Allison ’01, a Chicago native and School of Art alumnus. “I call them portraits, but they are really a document of a time and a place.”

One of his snapshots recently graced the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. The museum selected Allison’s work as one of 43 finalists—from more than 2,500 entries—for the 2016 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. An exhibition of these portraits is now traveling around the United States. When the three-year tour ends, the Smithsonian has indicated it may buy his work.

“I applied to the competition not thinking I would get it,” said Allison, whose work has been in the Tacoma Art Museum in Washington. It will be shown in Texas and Kansas City yet this year. “It’s a lot of exposure, which is fantastic. Anytime you sell a piece or win an award like that, it gives you confidence to keep doing that.”

This was the latest highlight in an art career marked by several high-profile developments in recent years. Allison has established representation at three galleries: Blue Spiral 1 in North Carolina, Habatat Galleries in Michigan, and Seeger Gray Gallery in California. He has shown at the prestigious international art fairs SOFA Chicago and SCOPE Miami Beach. Public collections in Alabama, Florida, Michigan, and North Carolina own his work, which sells for as much as $27,000 apiece.

“People are really validating what I do,” Allison said. “I never thought I would be in museums.”

Such an accomplishment is quite a reversal from a decade ago. He was ready to give up on his art career before one of his first portraits was curated into a show at the Muskegon Museum of Art in Michigan. “That was a big turning point for me to be in a public collection and to hear really good feedback from my work. I got a top-end gallery from that show.”

Allison had been blowing glass for about a decade before his big break. He was introduced to glass art through a course Jack Wax taught at Illinois State in the late 1990s. Allison had been a figurative painter up to that point. He quickly realized that glass was the perfect medium for his work.

“Glass to me is something that is so similar to the human characteristic: It’s sharp, it’s fragile, it’s transparent, it’s opaque, it’s broken. It can be smashed; it can break down. It can be repaired and patched. It’s so similar to the human condition that I love it for what I’m doing.”

By the time Allison left Illinois State, he had decided to pursue a career as a glass artist. After graduation, he moved to Asheville, North Carolina, at Wax’s suggestion. He spent the next few years honing his glassblowing skills in the artist-friendly city, meeting glass art pioneer Harvey Littleton. He worked odd jobs and for various artists such as Illinois State School of Art alumnus Joe Nielander, M.S. ’91, M.F.A. ’94.

It was Allison’s decision to begin using glass casting for portraits that revealed a public taste for his work. He started creating portraits while he was working as an assistant to prominent glassblower Dante Marioni at North Lands Creative Glass School in Scotland. Allison described his early portraits as more abstract and influenced by painting. The school’s director, Jane Bruce, suggested he attend graduate school at Australian National University where he could work under Richard Whiteley, a glass-casting artist whose work was more minimalistic.

It was there Allison developed the techniques he now uses for his portraits. He called special effects schools in Australia and Europe to learn how to take an impression from life, incorporating what he learned into his current life-casting process.

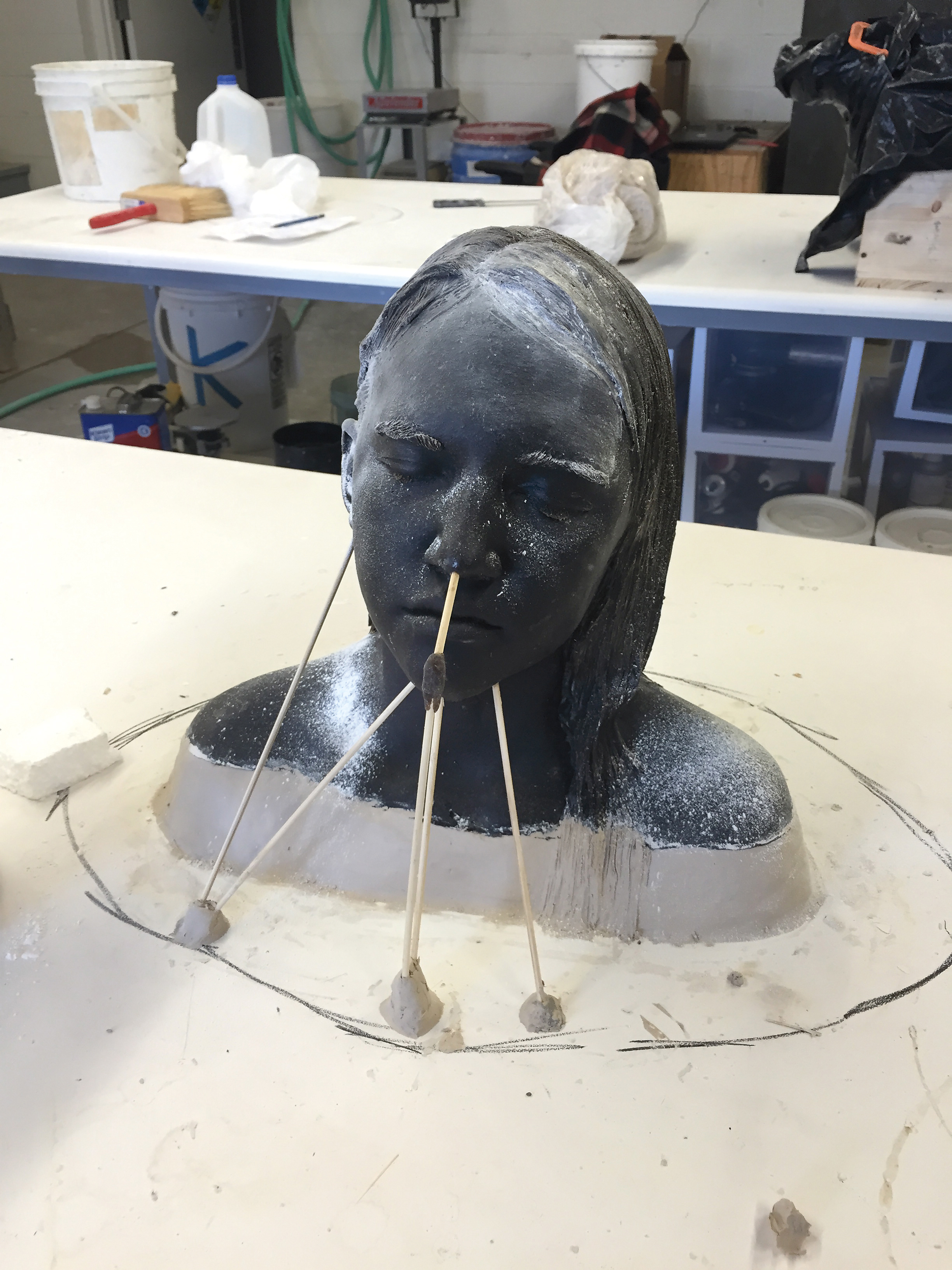

Allison coats his subject in a platinum skin-safe rubber to form a mask. Then he backs that up with a plaster shell from which he makes a wax. He manipulates the wax, adding features such as clothes and hands or softening the material to form a gesture or movement. He makes another mold off the wax, investing the material with plaster silica, then steams or burns out the wax.

Finally, he adds glass to the work by blowing glass into the mold, ladling hot glass into the piece from the furnace, or placing the mold into a kiln and filling the piece with commercial glass. The piece is allowed to cool for several weeks. The entire process takes about two months to complete, though times vary because he is always working on several different pieces.

Allison’s subjects are usually people he knows or would like to know. He has created portraits of his parents and of his niece wearing a snorkel and a mask (right). He has been working on a full-body cast of his wife taken last year while she was pregnant.

The subject of his Smithsonian portrait is a man named Grover. He was a well-known but seldom-heard-from character who resided in the small town in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains where Allison still lives.

From the outside, it looked like Grover spent all his days picking up trash to recycle. Allison later learned Grover spoke five languages and was making art out of the recyclables. Allison titled his work “What would the earth look like if all the shadows disappeared?”—a quote borrowed from the writer Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita.

“Grover just has this really interesting face and mannerism. Everyone knows his face, but nobody really knows him,” Allison said. “He is this fascinating guy who lives on the outskirts of society. He is kind of like a shadow, and that is how the title came to be.”

Allison’s art career has taken him across the country and around the globe. He has studied or conducted workshops at several prominent glass art institutions including the Pittsburgh Glass Center, Corning Museum of Glass, and Pilchuck Glass School. He worked in Turkey and was asked earlier this year to teach in Israel.

Allison still appreciates his days at Illinois State and credits Wax for motivating him. “My relationship with Jack Wax was one where he really pushed me. He would always make me feel that I wasn’t going to succeed in glass. I may not have been as persistent if I didn’t get that from him.”

Wax is impressed with the scale of his former student’s work and his individualistic uses of color and texture. “He has imparted his own image into the objects he is making,” said Wax, who is now a professor at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“I did doubt him,” Wax admits. “I saw that he had potential, but he was a young guy who was enjoying his life. I’m proud of him up to a point. I’ll be even more proud of him once he pushes his work.”

Allison plans to do just that, though he will do commissioned portraits and more commercial pieces to help pay the bills. He is building a glass studio at the North Carolina Penland School of Crafts, where he has worked since 2010 and is currently an artist in residency.

Once his studio furnace is finished, he wants to work with how glass flows into the mold in order to experiment with coloring and capturing the translucency of skin. The idea would be to add painterly aspects into the glass in a style reminiscent of figurative artist Lucian Freud’s work.

Overall, life is good for Allison. He teaches a couple of workshops at Penland and spends most of his time either working on and marketing his art or tending to his infant daughter, who will no doubt someday be immortalized in

one of her father’s glass portraits.

Behind the scenes

Dean Allison engages in a multistep process to create his glass portraits. These photographs were taken while Allison worked through different pieces.

Editor’s note: The Outwin 2016 American Portraiture Today exhibit will be in the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi through September 10. It will then be on display from October 6 to January 7, 2018, at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri. To see more of Allison’s work, visit deanallison.net.

Kevin Bersett can be reached at kdberse@IllinoisState.edu.