This year, ISU Pride turns 50. Its history mirrors the LGBTQ+ movement in the United States. Throughout the decades, the organization has offered a sense of community and family, a hub for education and activism, and a place of refuge for Illinois State University students.

What we now know as ISU Pride was born in 1969. Throughout the years, the organization would grow and progress as the spectrum of the community became more visible. Following pivotal moments in LGBTQ+ history provides insights into the evolution of Pride, and its impact on generations of the Redbird family.

Stonewall and the Gay Liberation Front

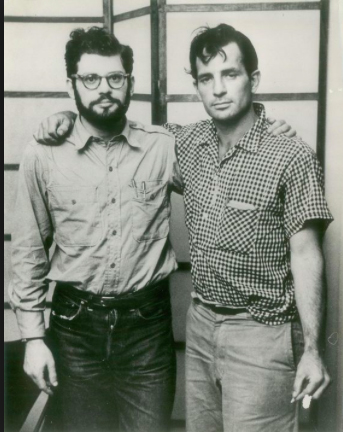

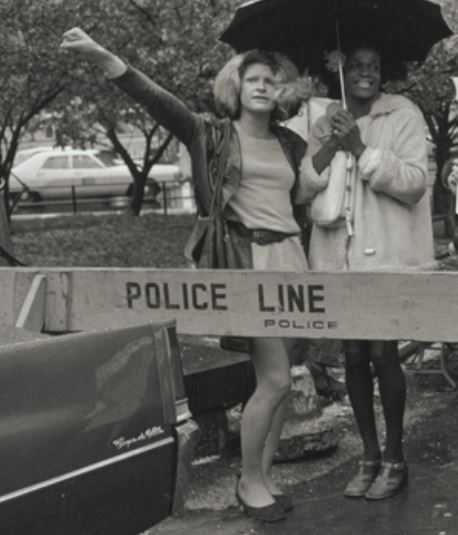

(Left) Transgender activists Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson were part of the force that established the first Gay Liberation Front in New York City in the wake of the Stonewall Uprising.

Even by the late 1960s in the U.S., almost every aspect of LGBTQ+ life was considered illegal, from dating and marriage to gathering in public. The American Psychiatric Association considered homosexuality a mental illness. Those who were exposed as LGBTQ+ faced violence, stood to lose their jobs, were evicted, or incarcerated.

Police often raided bars and clubs where LGBTQ+ clientele were known to gather, and arrested patrons for indecency. In the early hours of June 28, 1969, New York City police raided a bar in Greenwich Village called the Stonewall Inn. Police estimated more than 400 people came to defend those being arrested. The first iteration of a gay civil rights organization, known as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), emerged from what became known as the Stonewall Uprising.

ISU Pride began as a chapter of the GLF, formed at Illinois State in 1969 under the leadership of student Jim Curtis. The group decided to hold its first dance in March of 1970. “It was to be held on the top floor of Fairchild Hall, known as the Solarium,” said Emeritus Professor of English Robert Sutherland.

Now in his 80s, Sutherland was asked to observe the dance as a member of the newly formed American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in case there were any violations of civil rights. “The ISU football team had threatened to ‘bust up’ the dance, so everyone was nervous,” said Sutherland, who added that in response, students from the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) arrived to stop the football players. “The football team never showed, and the SDS members ended up dancing with everyone else.”

In a twist of fate, famed Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, engaged to speak at Illinois Wesleyan University, heard about the dance and decided to attend. “There was a good band playing. In the otherwise dark room a strobe light was thudding rapidly on and off,” recalled Sutherland. “Long chains of dancers snaked around the floor frozen in mid-motion by the flashing light. Allen Ginsberg, in dashiki and love-beads, sat cross-legged on the floor, writing a poem.” Ginsberg later typed up the poem and sent it to Curtis. When Sutherland gave Ginsberg a ride back to his hotel that night, the poet turned to him and asked if they really called the town “Normal.” Sutherland answered, “Yes, they do.”

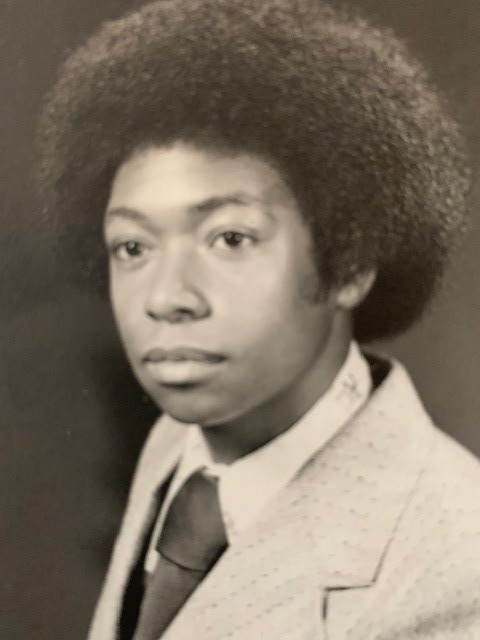

By 1971, the group took the initiative to become an official student organization at Illinois State, which would include some funding from student fees. The application came to the Student Government Association’s Appropriations Committee. Sitting on the committee was SGA Chief of Staff Nile Rowan ’74. “I was one of 250 black students at a school of 16,000,” said Rowan, noting he felt the students standing before him were kindred spirits. “I looked at this group and thought they were some of the bravest people I’d seen.”

When members of the Appropriations Committee wanted to reject the application, Rowan made the argument that the University funded clubs to promote understanding. “They were asking for money to help educate students about what gay life was like. Finding avenues to understand new ideas—something different from yourself—is the point of a college campus.”

Rowan persuaded his fellow committee members to approve the funding for what would officially become the Gay People’s Alliance (GPA). Though he fought for them, it was an organization Rowan would never feel comfortable enough to join. “I was at a very conservative school in a very conservative town,” said Rowan, who now lives in San Francisco with his husband and was not out until he left Illinois State. “There were no role models back then to say it was okay to be gay.”

It was a risky thing to be out in a place that was not our house, our friends’ house, or the GPA. —Jack Davis

Early GPA member Ellen Jahn remembered the organization was a target for letters to the editor in The Vidette and The Pantagraph. “The University was very courageous to support us in the era,” said Jahn, who attended Illinois State from 1970-71. Another GPA member routinely responded to the negative letters under the pseudonym Jennifer Willie. “To this day we call ourselves ‘The Willies,’” said Jahn of her female friends.

For alumnus Jack Davis ’73 ’75, the group represented one of the few places he did not have to hide. “It was a risky thing to be out in a place that was not our house, our friends’ house, or the GPA,” said Davis. “The atmosphere in Bloomington-Normal during that time was that everyone was closeted.” In fact, Davis remembers that community members would come to meetings as well. “GPA was the only public place where we could get together.”

Discovering a community was key for Dave Bentlin ’88. “I grew up on a farm in rural Central Illinois before the Internet, social media, smart phones, dating apps—anything that could connect a gay person to their LGBTQ community,” said Bentlin, who has worked at Illinois State for more than three decades. “I came to ISU seeking that community and I found it through the Gay People’s Alliance. The sense of isolation and loneliness subsided, relationships and friendships formed.”

The GPA brought activist Barbara Gittings on campus. Image of Gittings protesting in front of the White House in 1965. Photo by Kay Tobin Lahusen and housed at the New York Public Library

The GPA worked to bring speakers and entertainers to campus with Davis often playing host with his friends living in a house on Mill Street. “We would go to the airport, pick them up, feed them dinner, take them to the speaking engagement, and bring them back to the house so they could spend the night,” said Davis. Speakers included nationally recognizable names like Barbara Gittings, the “mother of LGBT activism;” Elaine Noble, the first openly lesbian candidate elected to a state legislature; and feminist comedian Robin Tyler. The group also hosted speakers for their meetings, which Davis noted reflected the initial focus of the group on gay men and lesbian women. “We had a transgender speaker come down from Chicago. I’m sorry to say we asked questions like, ‘Why would you want to change?’ We weren’t there yet,” he said of the slow inclusion of queer, transgender, and non-conforming members of the community.

The GPA also began a long tradition of education about LGBTQ+ life with tabling (setting up an information table) at a local festival. “There was no verbal confrontation, but people made it clear they did not want us there,” Davis said. “Now that I think about it, it was an extremely brave thing for us to do.” They also established a speaker’s bureau for campus, offering to speak in sociology, psychology, and anthropology classes. “We had to be careful to check who was in the class before going to speak, so we were not outing any members to roommates or friends,” said Davis. “I can’t tell you how careful we had to be. How closeted we had to be. We didn’t even keep a list of members so that nothing was written down.”

That taboo mentality left education major Rose Adams ’74 in fear that being out would mean never teaching. It was only after graduation she reached out to GPA and felt connected. “Through GPA, I learned about gay culture, literature, women’s music, and available resources. We had picnics and parties. We met with both gay and straight members of the community to foster better understanding.”

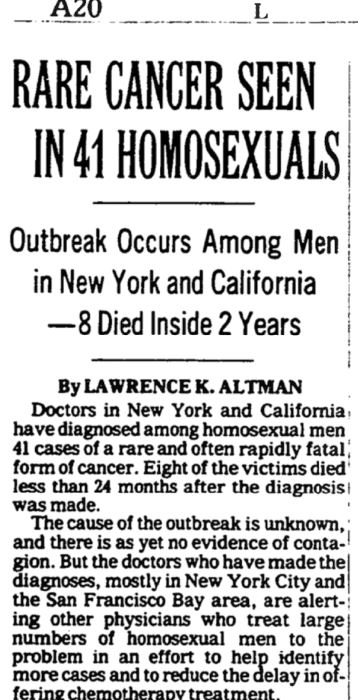

New York Times article reporting a “rare cancer,” which would later be determined to be AIDS. From The New York Times Timeshare.

Education and understanding would become even more vital in the coming decades of the 1980s and 1990s, as an unknown illness took hold.

The silence surrounding a ‘rare cancer’

In 1981, several men were diagnosed with what the New York Times called a “rare cancer” that seemed to attack the immune system. The term ‘acquired immunodeficiency syndrome’ (AIDS) appeared in 1982 with thousands already dying from the disease. A majority of those first infected with HIV—the virus that causes AIDS—were gay men and trans women. According to the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR), between 1982 and 1992 more than 200,000 people in the U.S.—no matter their sexual orientation or gender identity—died from AIDS.

“People were petrified by their homophobia,” said Sutherland, who served as faculty advisor for the GPA from 1990-1992. “President [Ronald] Reagan would not even refer to AIDS until 1985, when people were already dying in droves. It wasn’t until Surgeon General C. Everett Koop demanded that AIDS be considered an epidemic that people in general and the medical establishment began to act.”

Alum Jack Davis took part in one of the first performance protests in San Francisco in 1984, calling for money for AIDS research. Photo by Jack Davis

After graduation with a master’s degree in fine arts, Davis worked at the McLean County Arts Center before moving to San Francisco in the early 1980s. He found his activist work with the GPA helped give voice for a new cause. “There was no government support or public funding to fight AIDS,” said Davis, who was recently celebrated for his work with the group Enola Gay. Davis is recognized as orchestrating the first act of civil disobedience to bring attention to AIDS—a protest performance outside San Francisco’s Livermore Labs in 1984. “I knew we had to do something,” he said.

Back on campus, Sutherland remembered an Illinois State chapter of ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) performing a “die-in” at an Academic Senate meeting. “Students stormed into the meeting and started ‘dying’ on the floor to galvanize the Senate to pass a resolution putting ISU on record as taking AIDS seriously. It caused a huge flap,” he added with a smile. “ACT-UP was independent, but the GPA supported the action.”

Illinois State’s Gay People’s Alliance took part in the Chicago Gay Pride Parade in the late 1980s. Photo from Denise Goff

Though small in number in the 1980s, the GPA forged on with the speaker’s bureau and campus events. “There were about four or five of us doing all the in-class talks,” said Denise Goff ’86 ’04, who served as the GPA president from 1985-1990. “You have to remember that this was a time before the Internet, before Google. We did get some questions about AIDS, though most people dismissed it as a gay man’s disease, even when straight people were dying.” Goff joined the McLean County AIDS Task Force, which pushed for education amid myths and ignorance about the disease. GPA members advocated for the showing of several panels of the AIDS Quilt, and attended several gay pride parades in Chicago. “The fear was still there, but being seen and heard was so important,” she said.

In the face of the horror of AIDS, many in the United States were forced to recognize the discrimination facing the LGBTQ+ community. Goff recalled that registered student organizations (RSO) would have the chance to have breakfast with the University president to address issues of concern. When Goff sat down with then-President Thomas Wallace, they pointed out that sexual orientation was not part of the University’s non-discrimination policy. As a result of her efforts and Wallace’s understanding of the issue, Illinois State’s affirmative action policy added sexual orientation in October of 1989.

For members, GPA provided a place for students to feel heard and accepted. “You weren’t always allowed to be out, and you weren’t always allowed to feel safe,” said Goff. “It made a difference to know there was a gay, lesbian, and bisexual community at ISU.”

“It was our own code,” said Mark Vegter, a 1993 Illinois State graduate who has worked at the University for more than 25 years. “We would ask, ‘Are you going to GPA?’ and people who might overhear would assume were we were talking about our grade point average.” After graduation, Vegter returned to GPA, which changed its name to the Gay and Lesbian Alliance (GALA). “It was an effort to be more inclusive toward women,” he said, though the group quickly realized they needed a name that would adapt through time to include more members of the queer community.

“We were GALA for about five minutes,” joked Barb Dallinger ’81 ’01, who became the group’s co-advisor with Professor Chris Horvath. “They went for P.R.I.D.E., which was the all-encompassing People Realizing Individuality Through Diversity and Education, but now we just call it Pride,” said Dallinger, whose devotion to the Pride students is part of a personal mission. During her undergraduate studies at Illinois State, Dallinger faced intense bullying and fear. “Pride is that safe space that I didn’t have,” she said. “Letting the students have that is very important to me.”

In 1998, the fear of bullying and violence against queer people grabbed national headlines and became embodied in one name—Matthew Shepard.

Forward motion in the wake of a tragedy

In October of 1998, 21-year-old University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard was horrifically beaten, tied to a rural fence, and left to die. The assailants admitted they targeted Shepard because he was gay. News of the hate crime shook the nation in its brutality.

“It was just such a shock,” said Dallinger. “It’s like you already don’t feel safe. But now you really don’t feel safe. I’m already worrying about [the students] constantly. And all of a sudden it became very real. You just kept feeling, ‘This could go bad so quickly. This could happen here. This could happen here.’”

Students in Pride organized a candlelight vigil they called Rally for Love. The day of the rally, one student sat in class and listened as her instructor made a homophobic slur. Dallinger recalled the student telling her about the incident. “She literally stood up in the middle of the lecture hall, and said, ‘Today of all days, I am not remaining silent. When you say things like that. I am walking out of this class,’” Dallinger said. “And she did. And other students followed her.”

That student was Pride President Kristy DeWall ’01 ’03 ’07, who helped organize the vigil. “The time surrounding Matthew Shepard’s death was pretty rough. We had to balance our lives as students knowing that it could be any of us,” said DeWall, writing from the Air Force base in the Middle East where she now serves. “More than 1,000 people gathered on the Quad in solidarity [for the Rally for Love].”

Outside of the fear, DeWall said there were daily, constant reminders of the battle for respect. “People would deface our meeting flyers and sidewalk chalks for events like World AIDS Day,” said DeWall.

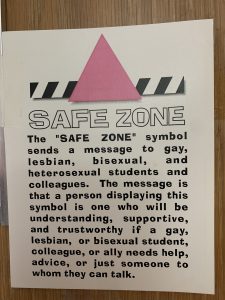

“It wasn’t just the students,” said Vegter, who became the advisor for Pride after Dallinger. “We would get complaints from people who said they felt ‘uncomfortable’ seeing the flyers. And some staff members would just pull them down.” After the Rally for Love, Mike Schermer and Jane Reggio of the Office of Student Life worked with Vegter, Dallinger, Jill Benson, and Lin Hines to create “Safe Zone,” a training program for faculty and staff members. “I think Safe Zone did a lot for this campus in terms of opening people’s eyes about what students were facing,” said Vegter.

“When we finished the training scenarios [for Safe Zone], we would tell the participants, ‘These are real situations our students have experienced,’” said Dallinger. “And you could just see their eyes grow huge. They didn’t think it happened here. And we could not have done those scenarios if we did not work with the [Pride] students.”

Education and activism remained key components of Pride. “We focused a lot on legislation around hate crimes,” said Rachel Spangler ’05 ’07, who took over for DeWall as president of Pride. The group traveled to Springfield to meet with lawmakers about a statewide non-discrimination ordinance. “We were trying to effect change on campus and in the larger community.”

One aspect of education and outreach has only grown over the years. The annual Pride Charity Drag Show began in 2008, and drew in more than 1,000 attendees last year to the Brown Ballroom in the Bone Student Center. “Putting the show on takes a lot of work and coordination and it shows that Pride is committed in bringing the event to the campus and community,” said Tracey Vogelsang ’04, who was on the Pride board when the show launched with just a few acts.

“This is more than just a drag show,” said Sharon ShareAlike, who has hosted the show for years. “We are all one big family, gathering together once a year to celebrate each other.” An alumnus of Illinois State, ShareAlike said the feeling of acceptance from the audience can transform performers, some of whom are students performing for the first time. “I am always amazed by the amount of courage these performers are able to find in themselves,” she said. “As soon as they hit the stage, the crowd accepts them with open arms and thunderous applause. From that moment the performers know they are safe and they instantly begin to light up.”

Along with supporting the LGBTQ+ Support Fund, proceeds from the show also benefit area charities. “The show has raised a lot of money for community organizations and has shown Bloomington-Normal that LGBT students at ISU are invested in the area.” Vogelsang and her wife returned to volunteer for the Midwest Bisexual Lesbian Gay Transgender Asexual College Conference (MBLGTACC), when Pride hosted it at Illinois State. “It was incredible to see the RSO’s strength and support,” said Vogelsang, who is a social work case manager for people living with HIV.

The education associated with Pride happens both externally and internally as black and brown queer people, transgender people, and gender non-conforming people fought—and continue to fight—for visibility. Toni Marie Preston ’18 served several roles in Pride, including co-president. She started as a liaison to the University Program Board. “While UPB had a cis-caucasian, normative demographic, I took focus in strategizing on representing the entire LGBTQ+ demographic with more focus on QTPOC (queer, transgender, people of color) demographic,” said Preston, who is a speaker and advocate for intersectionality, abolitionism, and radical liberation.

Today’s Pride group meets in the LGBTQ+ Queer Studies Institute on campus. “Pride students felt strongly that there was not a space on campus where they could be themselves,” said Bentlin, who helped to found the institute in 2009 along with retired faculty members Becca Chase and Paula Ressler. Along with education, Pride focuses on building bridges with other groups on campus. “It’s not just about LGBTQ+ issues, it’s about how those intersect with other organizations,” said current Pride Vice President Annelise Leber. “We look to work with other student groups—especially those that represent people who are marginalized—to create understanding and support.”

Each year members of Pride honor graduates at Lavender Graduation, which began through Illinois State’s Women’s and Gender Studies program in 2015. “The students of course selected Mama Barb [Dallinger] to give the keynote speech, and she was amazing,” said Mandy Dartt ’03 ’15, who helped launch the ceremony after seeing the incredible impact that the Umoja ceremony had on students and the campus community. “Lavender Grad serves as an opportunity to celebrate the unique experience and accomplishments of the LGBTQ+ community.”

Education and speakers continue to be part of the work of Pride as the community progresses. The group brought in transgender activist—and Stonewall leader—Major Griffin Gracy to speak in 2017. Dartt said the talk reminded her there is still a long way to go for LGBTQ+ rights. “Though we are in 2019 and things have changed dramatically in the last 50 years, it is still fundamentally more difficult for a student with a marginalized identity to succeed on a campus full of people who don’t look like them,” said Dartt. “Pride in collaboration with multiple diversity groups on campus continue to work on behalf of the community to increase education, visibility, and equality as part of their mission, vision, and values.”

‘Pride saved my life’

Activism. Education. Safety. Community. Pride has represented many things to many people over the years, including a home. “The other members of GPA were my family,” said Jahn, who retired as an attorney and activist, challenging state systems to be able to adopt her children. “As an attorney during the AIDS crisis, I did wills for gay people who were dying from the disease. I pretty much never stopped objecting to injustice, and I never will.”

For some, finding a place to feel comfortable in their own skin translated into discovering their voice. “Illinois State was the first place I was ever out. It was the first place I was ever completely me,” said Spangler, who became a successful author. “I never had that before Pride. It gave me the confidence to start speaking out and seeing my life in my stories.”

Toni Preston rallying at Chicago Pride for trans lives and the decommercialization and extortion of LGBTQ+ people.

“I honestly feel like Pride saved my life,” said DeWall. Before attending Illinois State, DeWall survived an anti-gay conversion therapy that ended with a tattoo on her arm to remind her to commit to denouncing herself as a lesbian. The tattoo has been altered, and so has DeWall’s life. “When she was ready, she had another tattoo put over it,” added Dallinger, who calls the Pride students “some of the bravest people I know.”

Preston noted the experience she had with Pride leadership shaped her approach to activism. “I gained skills on how to positively (exploit) and impact the BQTGNC (black, queer, trans and gender non-conforming) community and the overall black community, so they could be educated about our culture as well,” said Preston, who conducts workshops and engagement coaching through her own company ToniMariePreston.life. “This was the beginning of honing my skills and owning a platform in Chicago’s advocacy community, which allowed me to feel confident, empowered, and unapologetic.”

Though the impact of Pride has been life-altering for some, for others it has provided them the small boost they need to make change. “I would say confidence has been a big thing,” said Leber. “Working with Pride and Diversity Advocacy helped motivate me to come out to my family, because I want to be able to talk about my life and the stuff that interested me.”

Dallinger said throughout the years she has seen students find something they need through Pride. “I think there are two extremes now,” said Dallinger. “There are the students who have been out since they were 12, and have served in their GSA [Gay Student Alliance] since junior high school, and their parents have met their girlfriend and love them. But there are also still the students who are not out, are confused, and who don’t know what to do.” She said everyone needs that place to relax and be themselves. “They want to talk about the date they had Friday night, or the fact that that boy they like actually talked to them,” she said. “Everyone needs that connection.”

For Bentlin, the idea that ISU Pride was there was sometimes enough. “I didn’t always attend the weekly meetings and didn’t always feel connected to the group, but knowing the organization existed and that there were other LGBTQ people in my backyard gave me great comfort,” said Bentlin, who leads the area community’s Prairie Pride Coalition. “I gained an identity that has helped my life feel full and enlightened.”

Adams called the organization a saving grace. “Honestly, I’m not sure how my life would have turned out had I not grabbed that GPA lifeline,” she said. “We supported each other through rough times. I saw that a good and full life could be possible. My confidence and sense of self-worth were boosted. And I met my future wife.”

Spangler hopes for another 50 years for the group. “Pride was always there for me, and I know it will be there for others,” she said.