An empty film canister makes a great nursery. Although it’s still difficult to see the gelatinous eggs laid by the thumb-sized poison dart frog, it’s a lot easier than finding them on the floor of the rainforest.

Appears InJust ask Assistant Professor Dr. Matthew Dugas, who has found them in both places. But where he usually sees them these days is in a fish tank in a walk-in cooler in his laboratory. A pair of light bulbs match the dim light of the rainforest floor, and temperature and humidity are carefully controlled. So carefully in fact, that if something goes wrong in the middle of the night, Dugas gets a wake-up call.

The brightly colored poison frogs are among the most toxic animals on the planet, with chemicals released from the skin of some species capable of killing humans. But it’s the ants and mites that the frogs’ sticky tongues pick up from the forest floor that make them toxic. When they’re raised on a captive diet of fruit flies, they’re harmless. Even in the wild, the strawberry poison frog (Oophaga pumilio), which Dugas studies, isn’t dangerous. Just don’t touch your nose or mouth after handling it.

The female lays a clutch of about six eggs and then disappears for a while. The male cares for the eggs, moistening them to keep them from drying out. When tadpoles emerge about 10 days later, the female returns to transport them on her back, one at a time, to an aquatic nursery. In the wild, that’s usually a pool of rainwater caught in the thick leaves of a bromeliad. In the fish tanks, it’s a film canister, a plastic shot glass, or a urinalysis cup. There’s competition for a ride, and not all tadpoles get one. Dugas is trying to figure out why some get picked up, and some don’t, as well as why the mother only takes one at a time.

“They get left there a lot,” he said. “You’d think the tadpole would be very incentivized to get on their mom’s back.”

Poison dart frogs of both sexes transport tadpoles, but females perform the bulk of the work in O. pumilio. Parents have good memories, returning to each leaf where it left an offspring.

“Their spatial memory is incredible,” Dugas said. “They know where their tadpole is and what leaf axil the tadpole is in. If you move the tadpole, they’ll go to where they left it because that’s where it’s supposed to be.”

A tadpole eats an average of an egg a day, needing about 50 before metamorphosis occurs. How often, how much, and how long a mom feeds a tadpole vary. Sometimes, the frequency, amount, and duration of a feeding depend on whether the tadpoles vibrate, and how well they do it. That leads to another question for Dugas.

“The purpose of this research is to understand the communication between parents and offspring. How do offspring tell parents about themselves, and what do parents do with that information?”

Dr. Matthew Dugas

“The big question I work on is how resources are distributed within a family. It can be a parent making a decision, it can be siblings fighting, or offspring generating signals convincing parents to give them food. And this has consequences. Tadpoles that don’t get a lot of maternal care come out of the water small, and never really catch up,” he said.

Tadpoles have advantages as a study system other invertebrates don’t have. If you stop feeding a baby bird halfway through development, it dies. If you stop feeding a tadpole, it just becomes a smaller frog.

“A tadpole gets more of a say in how long it stays dependent on parents than some other animals do,” Dugas said. “Most of the time offspring want more food, or want food for longer than a parent wants to provide. How does that get worked out?”

Dugas has found maternal favoritism, with mothers seeming to favor their more developed offspring, feeding larger meals to the older and bigger tadpoles, and the ones that vibrate more quickly.

“It’s hard to get your head around the fact that they’re little frogs doing all these things that are very familiar to us,” he said. “The purpose of this research is to understand the communication between parents and offspring. How do offspring tell parents about themselves, and what do parents do with that information?”

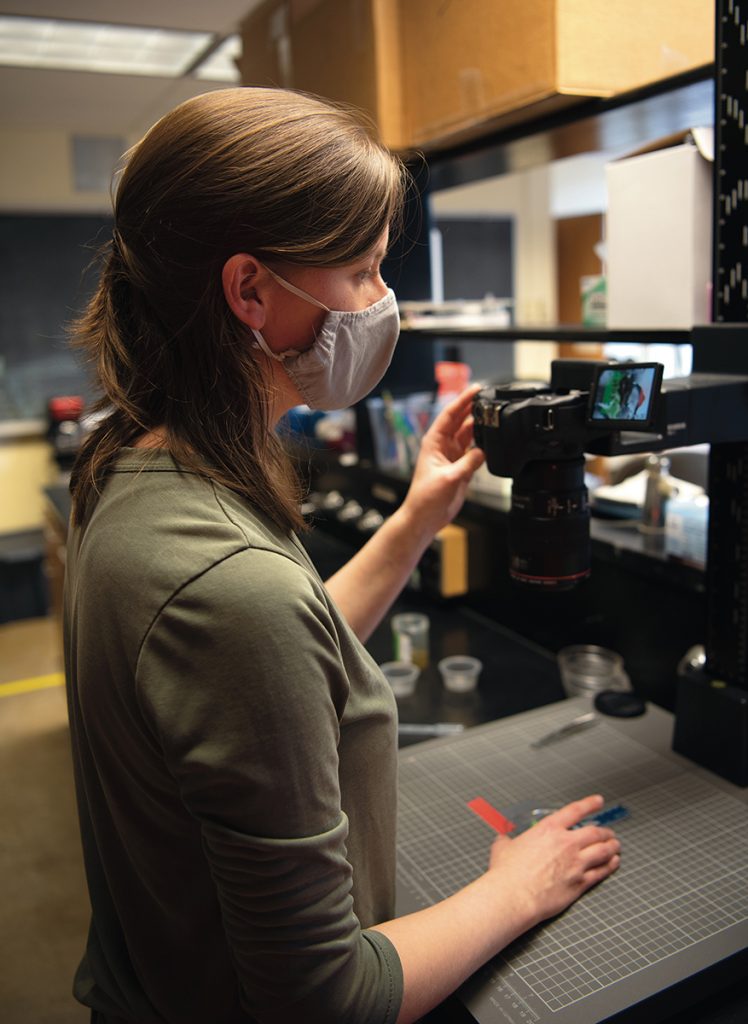

Dugas has spent nearly a decade observing the tiny poison dart frog, a tedious process where he has scanned video frame by frame, at 120 frames per second. When he studied them in Costa Rica, he would get up at 4 a.m. with a bag packed with cameras, set them up in places he knew had tadpoles, and loop back to change the batteries before picking all of them up at the end of the day and viewing the files to see if the mothers came.

Once the tadpoles are deposited, the female usually lays a “welcome to the world” clutch of unfertilized eggs. Eggs are the tadpole’s only food source, and mom visits every few days over the next six weeks to lay more.

The frogs are difficult to study in the wild, but it helps that you can attract O. pumilio by attaching plastic shot glasses to trees, providing a convenient place for parents to place tadpoles, and more convenient for researchers. Dugas has observed frogs climbing trees with tadpoles on their backs, stopping to rest along the way.

Occasionally the frogs transport two tadpoles at a time, but that’s rare. And they keep going back for more, until they don’t, he said. There’s obviously competition to be the first to be transported. So who decides who gets a ride, and where that ride ends—the parent or the tadpole?

Getting a ride enhances the chance of survival. If the female is disturbed along the way, the tadpole can fall right off, but when she shows the tadpole a potential nursery, she can sit in the water for hours before the tadpole comes off. Is there something sticking them together or is the tadpole just holding on for dear life?

“I know there’s something there,” Dugas said. “I know there’s something we can ask.”

And he will.