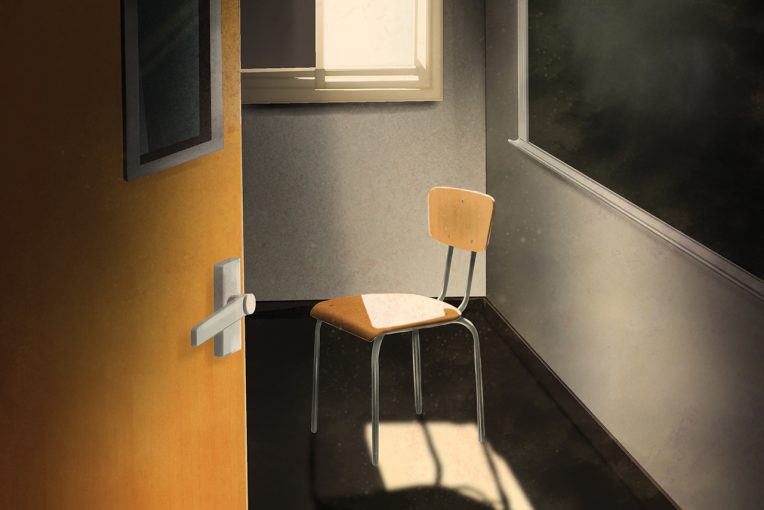

Public schools across Illinois locked students as young as 5 into isolation rooms, some no bigger than a phone booth, where the children were left to cry, beg to be let out, and dig their nails into padded walls, according to an investigation published in 2019 by the Chicago Tribune and ProPublica Illinois. When the story ran about Illinois teachers using such isolation rooms as punishment for students, including those on the autism spectrum, Illinois State University’s special education faculty stepped in to help.

Nikki Michalak was at a conference on autism when she received a text with a link to the article. The assistant instructional professor in the Department of Special Education (SED) emailed the Illinois State Board Of Education (ISBE) offering the help of Illinois State University faculty who had researched alternatives to the practice of seclusion, banned in certain states but still allowed at the time in Illinois.

Appears InWithin 10 minutes, Michalak received a response, and a few months later, ISBE awarded a $1.3 million, three-year grant to Illinois State through which faculty provide training, coaching, and resources for teachers in the districts identified in the story, along with free resources for any educator on how to support students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

The Autism Professional Learning and Universal Supports Project (A+) grant was received in February 2020, and grant staff were ready to head into the schools when they were closed due to the pandemic. The A+ team designed virtual training and started working with teachers online until face-to-face visits began in March 2021 when schools reopened.

And that’s where the princess story comes in.

One teacher reached out to Michalak and her team to help an elementary student who had been through a move and multiple quarantines, and wanted nothing to do with school. When her mother pulled up in the parking lot, the 10-year-old refused to get out. Michalak and her colleagues drove 90 miles to the school, got into the car with the girl, and spent an hour trying to persuade her to go to school. When she eventually got out of the car, she gave Michalak’s team a hug, turned around, and quickly climbed back into the car.

Still, Michalak considered that a breakthrough. After talking to the girl’s mother about her daughter’s special interests, she found out she loved princesses. Michalak drove to Target that night, loading her cart with princess-related items.

Michalak and her colleagues returned to the school the next day. When the girl saw the princess wardrobe, she hopped right out of the car. The clothes remain at school, where they are used as reinforcement for positive behavior.

“She could see school as a fun place, and not an adverse place,” Michalak said.

Success stories are multiplying as the SED team provides in-person training and coaching, she said. Although faculty have focused on districts identified in the Tribune article, they are also making online resources available to all districts and private special education cooperatives in the state and launched a website, autismplusil.org, in May. The site includes training modules for those who want to learn more about evidence-based practices for students with ASD.

“We’re trying to build them back up and let them know that we know they’re working with some children who have some significant support needs.”

Dr. Stacey Jones-Bock

Dr. Stacey Jones-Bock, associate dean of the College of Education, emphasized the A+ team is not critical of the teachers who lacked resources to find other ways to manage challenging behaviors. Instead, faculty recognizes teachers need more support, and that’s the purpose of the training and coaching.

“We’re trying to build them back up and let them know that we know they’re working with some children who have some significant support needs,” Jones-Bock said.

Monica Campbell ’88 is the principal of an Illinois special education cooperative. She reached out to the Illinois State team in May 2020 and shared some of the challenges her staff was facing. After visiting the school twice to observe, Illinois State faculty provided training on autism and best practices, along with information about the escalation/de-escalation cycle.

“By brainstorming with them, we were able to put our challenges under a microscope and problem solve situations such as transitions, which are often very difficult for students with autism,” Campbell said. “The result is fewer episodes of escalation.”

One in 54 children is diagnosed with ASD, with a ratio of four boys to every girl, Michalak said. ASD affects the neurological system and the ability to communicate, socially interact, and engage in developmentally appropriate behaviors. Much more is known about the disorder today than even 15 years ago, she said.

What looks like a behavior issue with students on the spectrum may actually be a communication issue. She compared it to a toddler who can’t communicate in words

but will grab you by the hand and pull you along until you figure out what they want. If they’re not successful, they cry.

“This is no different, except it might be a 6-foot, 240-pound individual,” she said. “And now grabbing the hand and pulling might seem aggressive.”

The use of isolation rooms to punish behavior is controversial, Michalak said. The practice is defended by some educators who say there are times when restraints are necessary for student and teacher safety. But in Illinois, students were being secluded regardless of the threat level and could be isolated for 30 minutes or more.

The day after the Tribune story appeared, Gov. J.B. Pritzker called for an immediate end to the practice, and the Illinois State Board of Education wrote emergency rules that immediately banned isolated seclusion. Seclusion is still allowed if an adult is present and the door is kept unlocked.

Also, a new state law will ban the use of physical restraints and severely restricts the use of isolation in public schools. At the federal level, a bill has been introduced in Congress, the “Keeping All Students Safe Act,” that would ban seclusion in all states.

Michalak and her team are focused on training teachers to identify “precursor behaviors” and learn how to deescalate situations before behavior reaches the point of becoming a safety issue.

“There’s a lot of proactive, positive approaches and strategies we can put in place that would change the outcome,” she said. “We want to make sure that we’re intervening at a time that prevents that behavior from getting bigger.”

And there’s more to be understood. Children with ASD may have sensory processing issues, being hypersensitive to touch, sounds, lights, or movement. Touch may be painful. The buzz of a fluorescent light or the hum of an air conditioning unit could cause anxiety.

When the girl saw the princess wardrobe, she hopped right out of the car. The clothes remain at school, where they are used as reinforcement for positive behavior.

Jones-Bock worked with a middle school student who was refusing to eat in the cafeteria, or even walk through it. Initially it looked like a behavior issue because he’d refuse to go or travel through it. When staff sat down in the lunch room, they realized it was the sound of the rooftop air conditioning unit that was bothering him so he started eating lunch in the library.

This isn’t the first time SED faculty members have provided support and resources to K-12 teachers. Jones-Bock and Michalak co-directed the Illinois Autism Training and Technical Assistance Project at Illinois State, a service-based grant that allowed faculty to go into classrooms and provide training and coaching from 2004 to 2013. The program had a strong family component with faculty visiting students’ homes and doing long-term planning to provide consistency across both school and home environments. When that grant ended, the support went away.

“A lot of the districts that were flagged (in the Tribune story) were districts that we had been in,” Michalak said. “So it’s almost like you rip the rug out, and teachers don’t have the support.”

Jones-Bock said the A+ grant allows that support to return in a new way. Schools are creating Behavior Change Teams (BCT), which include administrators, teachers, and paraprofessionals. The A+ team uses an environmental assessment to identify quality indicators of programs for children and youth with ASD. Based on the data collected, Illinois State provides training, supports implementation of interventions, meets with the team frequently, and is available for support. The BCT team then provides support to other schools in their district.

The unusual 2020-2021 school year, with students moving between in-person, hybrid, and remote learning, created more behavior issues when students returned to the classroom, said Dr. Allison Kroesch, SED assistant professor and co-principal investigator on the A+ grant.

“Just think how hard it’s been for parents to educate their children in their homes. If you have a typical fourth grader, and add autism to that, it’s a whole different situation. Parents are coping right now and they’re doing a fantastic job, but everybody’s just getting by.”

State law requires schools to report incidents of seclusion. The Tribune investigation found the Illinois database documented more than 20,000 incidents from the 2017-2018 school year. ISBE has a new data entry system that districts are using to track behaviors that result in timeout and restraint. That will enable the Illinois State team to evaluate the schools they’re working with to see if the added support is making a difference, Michalak said.

“We’ve been able to help them put supports in place, and tighten up some of the already good things they were doing,” she said. “We’re just filling in some gaps for them, and we’ve seen great success with their implementation in a really short time.”