Through a combination of anthropologic research and digital technology, it’s now possible to experience an immersive, 3D representation of a Guatemalan forest inhabited by the Kaqchikel people as it was more than 300 years ago.

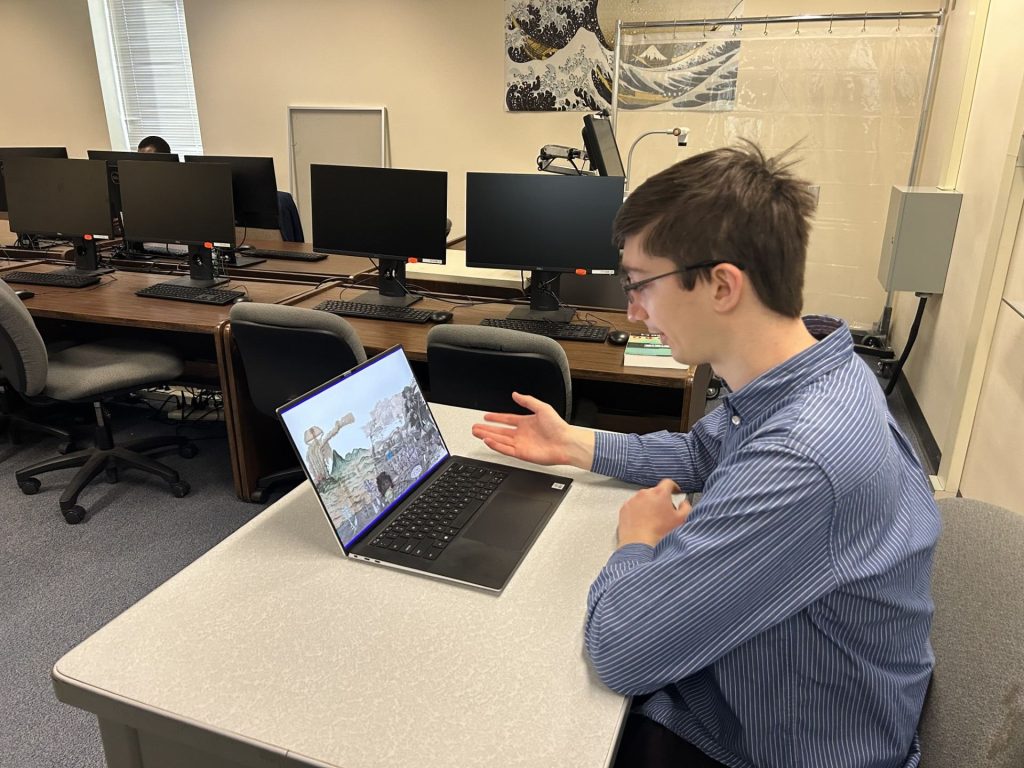

Dr. Kathryn Sampeck, a professor of anthropology at Illinois State University, and Creative Technologies major Noah Davison collaborated on a project to digitally present Sampeck’s research on the Kaqchikel, an indigenous Mayan people who live mostly in the highlands of southern Guatemala and southern Mexico.

Titled “A Maya Talking Forest: A Virtual Environment for Digital Repatriation of Kaqchikel Cultural Patrimony,” the project was funded by a FIREbird grant from the Office of Student Research.

“It’s important that cultural knowledge is digitally preserved and brought together,” Sampeck said. “Additionally, understanding Kaqchikel people requires walking in their world, and I think the framing of the entire concept is crucial.”

Sampeck studies pre-Columbian era practices and material worlds, investigating how they are affected by colonial dynamics and their lasting legacies. She wanted to share her research findings through an immersive video game format, emulating a walk-through museum tour accessible to users worldwide.

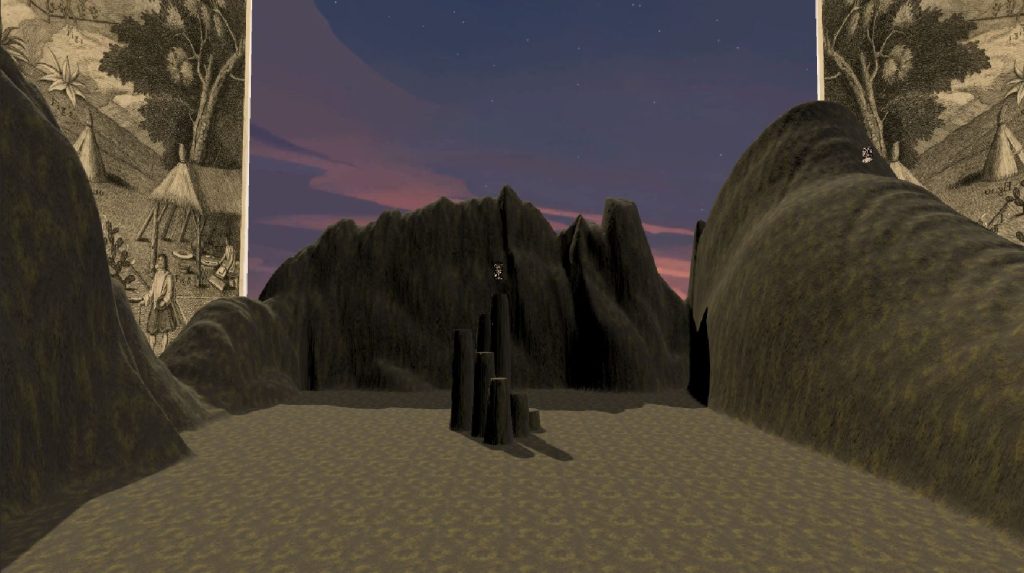

Using Unity to program the game, Davison developed a 3D environment that captures natural elements of the Maya Forest, specifically Guatemala in the early 1700s. Sampeck worked directly with members of the Kaqchikel community to ensure that the content was represented accurately. She also partnered with colleagues and scholars from Brown University, the John Carter Brown Library, and academics and educators in Guatemala. Ajpub’ Pablo García Ixmatá, a faculty member of Rafael Landívar University, is a co-director of the project and key liaison in Guatemala.

“The game is designed to reintroduce some of the culture that may have been lost due to modernization, globalization, and cultural diffusion,” Davison said. “We’re prioritizing making it mobile friendly, because a lot of people don’t have a PC or laptop that can run a more intensive simulation.”

Within the digital environment, participants have the freedom to explore their surroundings by selecting and engaging with various environmental elements. Upon interaction, a recording done by a native speaker of Kaqchikel says the name of the plant or animal and a text box emerges, providing information about the item along with its historical context. Additionally, vocabulary words are available in both English and Spanish, and Sampeck intends to extend this translation effort to include even more examples in the original Kaqchikel language.

“We created a game, but it’s more like a simulation,” Davison said. “You can move through a 3D environment that evokes some of the terrain and the fauna and flora.”

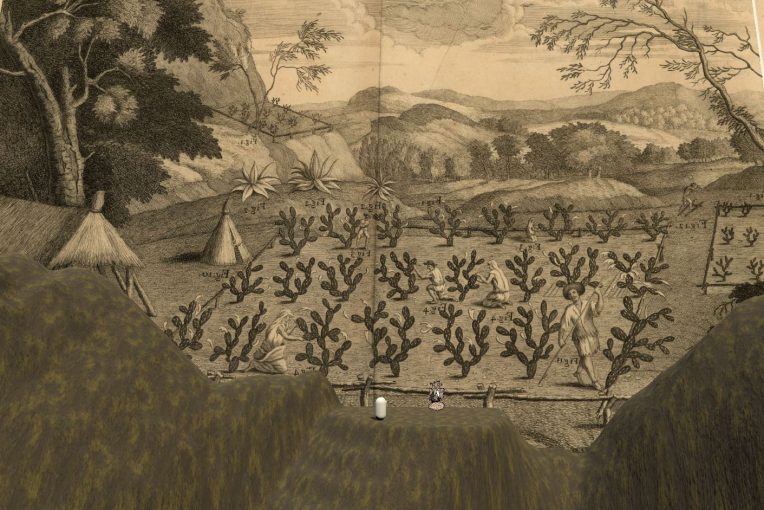

The elements in the game come from Sampeck’s research derived from uncommon Mayan books sourced from the John Carter Brown Library and illustrations from colonial travelers’ accounts and botanical and animal studies of species from the area.

“A big point I want to make is thinking about what has been lost and what may be there in the colonial records,” Sampeck said. “However, the Kaqchikel community is very much alive and vibrant. So, it’s a bit of finding that hidden history. They were by no means obliterated; they’re still alive and well. But, just like all of us, we want to understand our heritage better, and that’s what this project is all about.”

Creating the game presented its greatest challenge in coding the various elements and dynamic components that Sampeck and Davison aimed to incorporate. Despite the difficult moments, they agreed that the process was a rewarding one.

“That idea of preserving all the actual historical information but still creating something powerful and interesting is what’s been the most rewarding part of working on this project,” Davison said.

Driven by a commitment to accurately represent the Kaqchikel culture, Sampeck prioritizes their opinions, recognizing that their perspective matters most in portraying their own heritage.

In the future, Sampeck envisions further refining the game and facilitating a complete public launch for universal access. Her goal is to bring Davison to Guatemala for on-site exploration of the game’s included areas to enhance accuracy of the digital representation.