From remembering some of Illinois State University’s earliest graduates who were women to discovering the origin of the popular basketball phrase “March Madness,” historian Tom Emery explores this month in Illinois State University history.

March 2

On this date in 1960, Olive Lillian Barton, the Illinois State women’s dean from 1911-43 and a highly regarded figure on the campus, died.

Barton achieved her stature at Illinois State from an unusual upbringing. Born on January 28, 1874, she was a native of nearby Saybrook. Barton was one of three students in her high school graduating class. One of the other two was her brother, Charles.

Sadly, Barton endured a traumatic childhood. Her father, George Washington Barton, a physician and Civil War veteran, opened a practice in Saybrook in 1870. On December 28, 1885, he was murdered by another local doctor during a verbal altercation on the sidewalk outside a Saybrook drug store.

But Barton preserved and earned a two-year degree from Illinois State in 1899. She subsequently graduated with a bachelor’s degree from the University of Illinois in 1905, then earned a master’s from the University of Chicago in 1930.

Barton spent three years as the high school principal in nearby Lexington (1899-1902), then filled a similar position at Pittsfield in western Illinois (1902-04). During the 1905-06 school year, she was a high school mathematics teacher at Mount Vernon.

In 1906, she returned to Illinois State as a faculty member. Five years later, she was named dean of women, and commanded respect across the campus with her intellect, dedication, and genial nature.

Barton committed herself to the advancement of women’s rights and opportunities. In 1926, she was instrumental in the creation of the Women’s League, which became a hallmark of the campus for decades.

In a 1952 interview, Barton said that she wanted an organization “that would bind [women] together and make them feel as one.” The league became the basis for several related women’s groups, such as the Campus Sister movement and Honor Council, and held numerous dances and other social activities to bring the university together.

Barton remained a respected presence in the league. Every year, she hosted a dinner for the executive board of the group, including the incoming and outgoing officers. One example was on April 28, 1934, when she hosted the league officers at the Village Inn.

Her selflessness endeared her to the ISU community. With pride evident, Barton said in 1952 that “I count my friendship with the girls of Women’s League as one of the finest things that ever came into my life.” She routinely referred to the league women, and female students in general, as “her girls.”

Along the way, Barton rose to statewide and national acclaim. From 1930-32, she was the head of the Illinois Association of Deans of Women, and received a citation for service from that organization in 1940. Barton was also the membership chair of the National Association of Deans of Women from 1925-30, as well as a member of the American Association of University Women. In addition, she held membership in a host of local and state organizations, including Delta Kappa Gamma.

In 1935-36, she supervised publication of the first-ever Freshman Handbook at ISU. But by the early 1940s, her health began to fail, which led to her resignation on May 1, 1943.

Her departure was a sad moment for many on campus. Weeks before her resignation, a “Tribute to Our Miss Barton” came from the Women’s League in the Vidette on March 17, 1943. The narrative called her “the soul of Women’s League” who “has been the guiding light that has shown through the portals” of the group’s success.

Barton, wrote the tribute, was “always radiating happiness” with “an eye toward the future” in the development of the league. “You can count on Miss Barton’s ideas to be modern versions,” continued the writer. “Whether it be anklets or dates, tea costume or the best orchestra for that spring formal, she is always up to the minute—modern, understanding, and young with all of us.”

Indeed, she was “our cornerstone” from “her strength and guidance,” and was described with four words—“happy is the peacemaker,” which were “words [that] fit her so well.”

Six weeks later, her resignation was lamented in the Vidette, which said that “women will miss friendly helping hand [and] smile” of Miss Olive Barton, who was “ever ready, ever willing to help” with “sympathetic ears.”

In 1951, the Dunn-Barton residence hall, a red brick structure with 208 rooms, received its first students. The facility was jointly named for Barton and Richard Dunn, described by the Bloomington Pantagraph as “an early legal counsel to the Teachers College Board.” Dunn-Barton Hall served the University until its demolition in the summer of 2008, housing an estimated 25,000 students during its 57 years of existence.

Olive Lillian Barton, one of the most revered women in the history of Illinois State University, died on March 2, 1960, and is buried in her native Saybrook.

March 8

Today is International Women’s Day, a time to celebrate the achievements of women worldwide. In past decades, women had few of the opportunities of today and had to overcome a variety of gender and social restrictions.

In Illinois in 1900, only 16.3% of women were employed, with the exception of housekeepers. They were clustered in a handful of occupations, including teaching, which was 74% female.

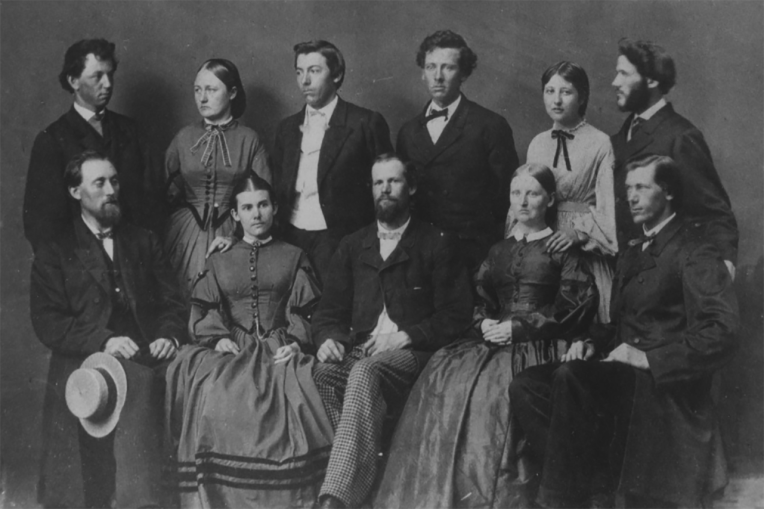

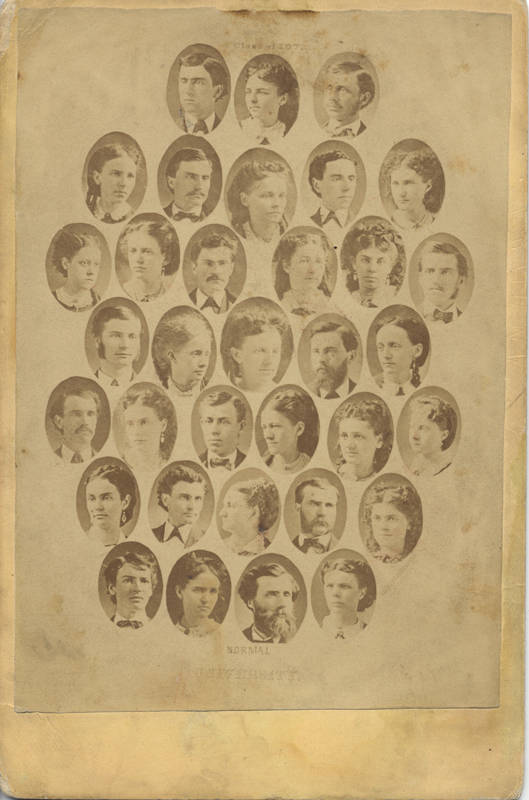

Since the original mission of Illinois State was the training of teachers, the University provided one of the few career opportunities for women. In a time when far fewer women were able to attend college, Illinois State and other “normal” schools were particularly important. The life experiences of the early women who graduated from ISU are an inspiration.

Women made up a high percentage of many early graduating classes at Illinois State. Four of the 10 graduates in the class of 1860, the first in university history, were female, as were 10 of the 15 graduates in 1866. Female graduates composed 14 of 19 in 1868 and 20 of 34 in 1872. In the final graduating class of the century in 1899, 48 of the 85 graduates were women.

Unfortunately, many of those women had to give up their careers when they married. In the original class in 1860, Sarah Dunn taught for only four years before her marriage, while Elizabeth Mitchell was a teacher for only four and a half years.

Even women who taught for long periods were often subjected to the gender norms of the time. Fannie Cole, who graduated from ISU in 1870, spent two years teaching “good manners and the etiquette of occasions” at various schools.

Still, many of those women managed to overcome. Rachel Hickey, class of 1872, followed a successful teaching career by becoming a physician and surgeon in Chicago. Along the way, she spent 23 years as a professor of histology and operative surgery in the Woman’s Medical College of Northwestern University, and was also an instructor of surgery at the University of Illinois.

Many alumnae of Illinois State became distinguished writers. Among them were Lida Brown, class of 1874, who combined a decades-long teaching career with great writing ability, publishing several books that included Classic Stories for Little Ones, Songs of Mother and Child, and Nature Study for Primary Grades.

Adelaide Rutherford, class of 1870, not only taught, but studied at the University of Michigan and published numerous magazine articles on a variety of subjects. Emma Robinson, class of 1868, published multiple works, including Women of the Mayflower.

Many took their talents around the nation. Eugenia Faulkner, class of 1878, spent most of her career in Kansas, including 10 years as a matron at the Kansas School for the Blind. From the class of 1869, Lizzie Alden was a teacher and principal in Kansas, as well as a primary teacher in present-day Oklahoma.

Julia Kennedy, class of 1871, eventually became superintendent of schools in Seattle, then was a school principal in Douglas, Alaska. A classmate from 1871, Frances Moroney, taught for 19 years in the Minneapolis area. Harriet Dunn, class of 1864, enjoyed a long tenure as secretary of the faculty at present-day UCLA.

Female graduates from the class of 1899 not only taught from one end of Illinois to the other, but also in California, Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota, and North Dakota.

Some took their ISU training around the globe, including Barbara Denning, class of 1870, who was a missionary teacher in Argentina for 16 years. Dorothea Beggs, class of 1898, eventually taught German at Iowa State and the University of Denver after studying in Germany for years.

Without question, the early female graduates of ISU experienced the sexism, oppression, and condescension of the era, which made their road to success even more difficult. Their perseverance, ambition, and will, however, won out, and their remarkable accomplishments are part of the legacy of Illinois State.

March 21

Today, the first round of the NCAA men’s basketball tournament begins, part of this year’s version of “March Madness.” Many believe the phrase has its origins in a graduate of Illinois State.

Henry Von Arsdale Porter, a 1913 ISU graduate, is widely credited with coining the phrase “March Madness” in 1939, while he was serving as an assistant executive secretary for the Illinois High School Association. Oddly, Porter used the words in a literary sense, rather than as sports jargon.

Born in the Mason County town of Manito, southwest of Peoria, on October 2, 1891, he grew up on a farm near Washington and later enrolled at Illinois State in Normal.

There, Porter apparently earned the esteem of his professors; one account claimed that all “agreed that [Porter] will reach high eminence in his chosen work.” His “eminence,” though, was not in teaching, but in two little words.

Porter graduated from ISU in 1913 and later coached and taught at Keithsburg and Delavan before settling in Athens, just north of Springfield. There, he put together a legendary run.

In nine years at Athens, Porter’s teams rolled to a combined record of 217-41 and never had a losing record. Two of his squads played in the state tournament, including the 1923-24 team, which went into the state title game at 29-0 before losing.

Following the 1927-28 school year, Porter moved into administration, becoming the assistant executive secretary of the IHSA. Part of his duties included editing the monthly magazine of the IHSA, the Illinois High School Athlete.

It was well-suited for Porter, who clearly showed some literary flair. In March 1939, he authored a seemingly insignificant article called “March Madness,” a tribute to the IHSA’s annual state tournament and its devoted fan base.

“When the March madness is on him,” wrote Porter, “midnight jaunts of a hundred miles on successive nights make him even more alert the next day.”

He waxed poetic in 1942 in another edition of the IHSA magazine, with a rhyme called “Basketball Ides of March” that again referenced the “madness.” Among the lines were “A sharp-shooting mite is king tonight / The Madness of March is running / The winged feet fly, the ball sails high / And field goal hunters are gunning.”

As Porter penned his words, the globe was gripped by the Second World War, and Porter was not oblivious. He closed his poem with “In a cyclone of hate, our ship of state / Is the courage, strength, and will / In a million lives where freedom thrives / And liberty lingers still / Now eagles fly and heroes die / Beneath some foreign arch / Let their sons tread where hate is dead / In a happy Madness of March.”

By the end of that decade, “March Madness” was regularly used by the IHSA as a nickname for the annual state basketball tournament. The term was first applied to the NCAA tournament in 1982.

Porter’s two words were not his only contribution to the game of basketball. Some of his other ideas actually shaped high school basketball, and the game itself, more than his famous two words.

From 1940-58, Porter was the executive secretary and, not surprisingly, editor of publications for the National Federation of State High School Athletic Associations. He was also the first representative from high school sports to serve on the National Basketball Rules Committee.

In 1936, Porter published the first standardized high school basketball rulebook, and worked to create basketball and football rulebooks specifically for the high school level. He was the first to use motion pictures for the study of basketball techniques, and developed the fan-shaped backboard that was a staple in high school basketball until the 1990s.

Porter also redesigned the modern basketball itself, into a composite-molded, seamless 29½ inch model that was much easier to dribble. That certainly helped the flow of the game in another of Porter’s implementations, the 10-second line. His foresight ensured his induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1960.

Porter died in Florida on October 27, 1975, years before his beloved phrase was on everyone’s lips come March.

March 22

Today, the first round of the NCAA women’s basketball tournament begins. Women’s basketball is one of the most popular sports at ISU and elsewhere but, like women’s athletics in general, it has come a long way.

The Title IX clause of 1972 opened the door for most women’s sports, and is rightfully celebrated as a landmark in women’s athletics today. But for many years, women had no place to play, and limited opportunities for any sort of athletic involvement.

As a result, female student-athletes at ISU, and nationwide, were left to carve their own path. At ISU, interest in women’s sports grabbed a foothold with the formation of the Women’s Athletic Association (W.A.A.) on April 9, 1919. It is entirely possible that the organizers were inspired by national events; that same year, Congress proposed the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote.

The purpose of the W.A.A. was “to raise the standard of physical, mental, and moral efficiency among the women of [ISU] by developing ideals of health, sportsmanship and physical control.” Twelve women were listed as charter members, who qualified on a points scale on campus.

The W.A.A. quickly established its presence on campus, and proved effective at raising money, a necessary step in its survival. On February 3, 1921, the group sponsored a carnival and vaudeville event with booths and one-act comedies. A total of $125 was raised, a substantial amount in that era.

The group kept growing, and by 1927, the points requirement was discontinued. On March 16, 1938, the Vidette reported that “W.A.A. Rolls Reach Peak,” with 150 members, a number the paper called “abundant.”

Eventually, the name was changed the Women’s Recreation Association (W.R.A.), and the campus group became part of the national organization. In time, membership was also extended to any female student on campus.

Among its many other activities in 1940, the W.A.A. sponsored an alumni luncheon, organized a “hockey game between the varsity and alumni,” and published a news bulletin. Camping trips, skating parties, and “other kinds of outings” were offered, as well as “tapping and social dancing, [which] are taught to both men and women.” The group also planned a “Sports Day” in which other colleges came to ISU to “participate in games and social activities with students here.”

As is usually the case with inclusion, others besides women reaped the rewards. The Vidette noted that “men benefitted also” because the W.A.A. also organized some men’s intramural events and were included in the myriad of activities sponsored by the group.

Those activities included a Swing House, where students could join the swing dance craze, in October 1937 and a hayride in March 1947. Indeed, the dedication and foresight of the Women’s Athletic Association provided generations of ISU students with a connection to athletics in a time when women’s sports were struggling just to be noticed.

Read more about a cohort of trailblazing women from Illinois State who dedicated themselves to rewriting the national narrative of women’s athletics.

Tom Emery is a freelance writer and historical researcher who, in collaboration with Carl Kasten ’66, co-authored the 2020 book Abraham Lincoln and the Heritage of Illinois State University.