In the third installment of Milner Library recognizing the women of Illinois State Normal University and to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies program, this article focuses on librarians in honor of National Library Week. Ange Milner, our namesake, started the library, and Eleanor Weir Welch grew it to what we know today.

Angeline Milner was born in Bloomington on April 9, 1856. She was homeschooled until age 11 when she attended a private school and later Bloomington High School but did not graduate due to poor health. She took biology courses at Illinois State Normal University in 1875 and 1878 through the Illinois State Laboratory of Natural History, which led her to a job with the Director of State Laboratory of Natural History, Stephen Forbes. Her work cataloging the plants, animals, and books at the library sparked her interest in library science. During this time in 1889, the president of Illinois State Normal University, Edwin Hewett, received funding to hire a full-time librarian who would organize the books at five different campus libraries into one main library. She applied for the position at Forbes’ and her sister’s encouragement, and her first day at the university was February 1, 1890.

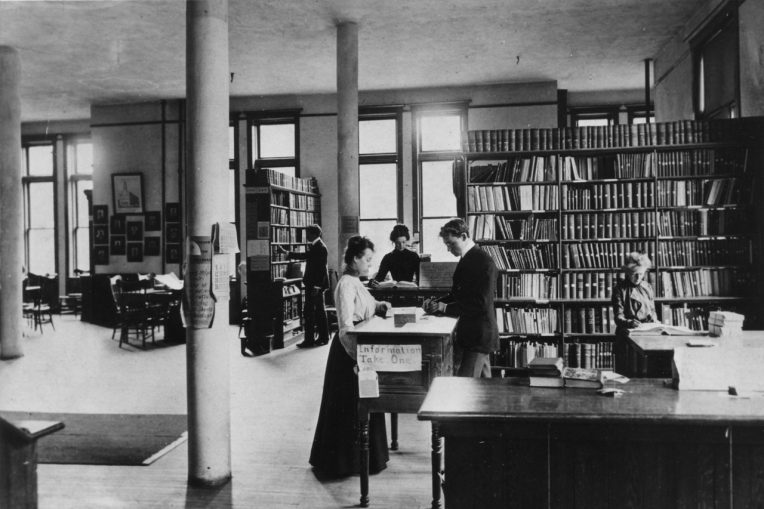

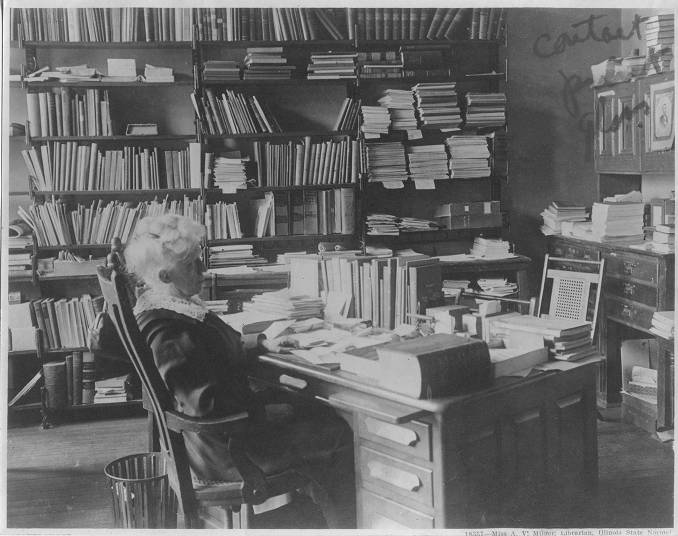

Milner first worked in several locations in Old Main then to the newly built Gymnasium, now called Cook Hall, in 1898, and finally to North Hall in 1914. She grew the library’s resources exponentially and created bibliographies for each class (a precursor to subject guides). She created strong relationships with faculty and students described in the January 19, 1928, edition of the Vidette after her death. Velma M. Horn described Milner’s demeanor as kind, earnest, and generous, and “a counselor for those in distress.” Wilbur M. Hoffman was quoted, “Service, the one word which she was such a living example, was surely her ideal.” Milner also compiled detailed files of every World War I service men and women affiliated with ISNU and wrote over 80 articles that helped librarians and teachers in rural areas.

In addition to her work at ISNU, she was a pioneer in the library field. She was a charter member of the Illinois Library Association, a branch of the American Library Association, and held multiple officer positions. She spoke at many national sessions about the importance of teachers and librarians working together to instruct students on how to use resources, and ISNU became one of the first to offer instruction.

Milner worked until her poor health forced her into retirement on October 15, 1927. She died on January 13, 1928, and it wasn’t until April 10, 2006, her 150th birthday, that a headstone was placed at her grave.

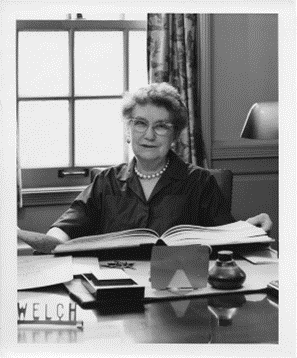

Eleanor Weir Welch

Eleanor Weir Welch was the second librarian of ISNU and was important to the growth of Milner Library. She introduced theory from her library degrees and advocated for a new building, a library for the laboratory school, library faculty positions, and defined policies to match other academic libraries. She grew the library’s resources even more and added new technology.

Welch was born in 1892 in Summerset, Iowa, and obtained her teaching degree from Monmouth College in 1914. In an article by Karen Schmidt about Welch’s life, Welch said, “I was a teacher because it was the thing you did when you finished college. And I got awful bored with it. It was the same thing; you studied and read more and read more and read more and your pupils couldn’t keep up with you… at least they didn’t; they could have but they didn’t.” She began working at her local public library and entered library school at the New York School in Albany in 1919, one of three in the country that required a college degree to enter. She became head librarian of the Wisconsin State Teachers College in 1920 for nine years, finished her degree at Albany in 1925, and received her Master of Science in Library Science in 1928. She focused on cataloging in her career up to this point, which was valuable to her time at Illinois State Normal University.

Welch was attending the American Library Association annual conference in 1928 when she met Gertrude Andrews, the assistant librarian of ISNU and acting head librarian after Ange Milner retired. Welch’s family had just moved an hour from Normal, so Andrews encouraged her to apply. Welch recounted her first meeting with President Felmley: “[He} looked at me and said, ‘Huh! You’re not very big, are you?’ I said, ‘Do you have to be?’”

When Welch started, she described the third floor of North Hall as too small for the needs of the university: “students… sitting on the window sills and… books piled in every possible place.” In her first few years, she added 20,000 books to the collection, made book selection the responsibility of library staff and not the president, and argued for a new library building and a library for the laboratory school.

Welch designed the new library (now Williams Hall) with every detail in mind. She surveyed libraries across the country “seeking advice on flooring, lighting, traffic patterns, and furniture” before funding was approved. She wanted to design a space that could grow with new resources. It was named in 1939 after Milner, and a year later, Welch wrote that the library “became a true college library.” It did not cost as much as other academic libraries in the state, but “its influence in use of color and design and its special services has been felt throughout the colleges of the Midwest.”

Welch also fought for a higher salary for librarians and staff. She worked with President Bone to give them the faculty rank of assistant professor in 1947, but the Teachers College Board would only give that status to librarians with the appropriate degrees. The verdict did open the opportunity for future librarians at the University to obtain faculty status. Welch then went to the Civil Service Commission to advocate raising the wages of the staff at the library.

Welch served as the president of the Illinois Library Association 1951-1953 . She focused on teacher-librarian training and promoting school libraries for most of her tenure, but she also spoke out against censorship during the McCarthy era. In the June 1953 ILA Message from the President, she encouraged librarians and library workers to band together against censorship. “Librarians have given books an important place in our culture,” she wrote, “so important that books are being attacked by those who fear a free mind and the discipline of individual taste and conscience, and by those who fear their complacency may be disturbed.”

She was aware of the role society placed on her as a woman, and though she didn’t identify as a feminist, she was quoted “I felt that a woman had as much ability, and often more, than a man in this position. But I didn’t think anything of it; it was just so.” She accomplished much in this position at Milner Library and chose the university over personal or professional growth in state and national organizations if she thought it would interfere with her work at Milner. She retired in the summer of 1959 and died on April 12, 1987.