An archaeological site in Central Italy dating back more than 2,500 years is a special place for two Illinois State University researchers. For the past three years, Associate Professor of History Kathryn Jasper and Professor of Art History Lea Cline have been leading the Northwest Bolsena Archaeological Project at Valle Gianni.

The excavation is the culmination of an interdisciplinary collaboration initiated more than a decade ago that enriches the duo’s respective fields, empowers students, and elevates Illinois State University’s research profile. This is the first Illinois State-led excavation in Italy and the only one currently led by an institution of higher education in Illinois.

Appears InDrs. Cline and Jasper began working at the site, which is located two hours north of Rome near the medieval town of Gradoli, in 2018. They secured an Italian federal excavation permit for 2020-2022 and a renewal through 2025. The arduous permitting process required the researchers to write the application in Italian and took months to prepare while they communicated regularly with both the town of Gradoli and the archaeological superintendency.

“We were very worried about getting a permit. It’s complicated and competitive,” Cline said. “It’s one thing to get the first permit, but they have since given us a three-year renewal. This shows we have done well, and they trust us. It is a mark of success for us.”

“We found what we thought was just an elaborate fountain, but what we thought was a single monument turned out to be only one part of a more complex site.”

Dr. Kathryn Jasper

Illinois State University and the professors’ respective colleges have rewarded and provided funding to Cline and Jasper for their work on this project. In 2020 Cline was named the Wonsook Kim College of Fine Arts’ inaugural Ken Holder Endowed Professor of Art. The College of Arts and Sciences recognized the project with the Interdisciplinary Award in 2020 and Jasper with the Shaw Teaching Fellowship in 2021 and a Faculty Research Award in 2022.

Last year, their research team was among the initial recipients of the University’s Office of Research and Graduate Studies’ Advancing Research and Creative Scholarship (ARCS) program. Their project received a two-year, nearly $200,000 award.

“The ARCS is a significant investment in the collaborative, interdisciplinary research that ISU faculty are doing, and we are so thrilled to be among the first recipients,” Cline said. “The award has given our project the opportunity to expand our research team, to buy advanced tools, and to engage in collaborations with partners both in the U.S. and in Italy.”

Cline and Jasper believe the award will enable them to transform the project into a world-class research enterprise by helping them secure larger federal grants from organizations like the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation. To build capacity, the pair have added three Illinois State colleagues to their research team: Dr. Abigail Chipps Stone, an assistant professor and anthropological archaeologist, and Drs. John Kostelnick and Jonathan Thayn, professors of geography. Their work will complement the directors of the excavation, whose individual characteristics make them exceptional partners, with Jasper envisioning the big picture and Cline focused on the fine details.

“Finding a site that worked for both of us was a challenge. We are 1,000 years apart in our specializations,” Jasper said.

Valle Gianni and the surrounding landscapes were occupied between 700 B.C. and A.D. 600, covering the final centuries of the Etruscan civilization, the entire Roman period, and the beginning of the medieval age. The archaeological site is in an understudied area west of Lake Bolsena, the largest crater lake in Europe. Previous research has focused on the population centers east of the lake where the Romans built a major road called the Via Cassia.

The Illinois State team hopes to illuminate the relationship between the ancient landscape of this region and those who lived and farmed there. Jasper and Cline seek to integrate what they discover about the people and land into larger narratives of Roman politics, economics, religion, and visual culture.

“We are still not sure what the Roman inhabitants of this site were doing in what is effectively the middle of nowhere,” Cline said. “But, by understanding it better, we hope to bring more clarity to the archaeological context of the western shore of this important lake.”

Each summer, the professors spend six weeks at the archaeological site and the rest of the year deciphering what they’ve found. They’ve already made some important discoveries.

“We found what we thought was just an elaborate fountain,” Jasper said. The foundation measures 6 by 8 meters and a depth of approximately 6 meters. “But what we thought was a single monument turned out to be only one part of a more complex site,” a fact revealed after ground-penetrating equipment used to map the area detected multiple areas separated by walls.

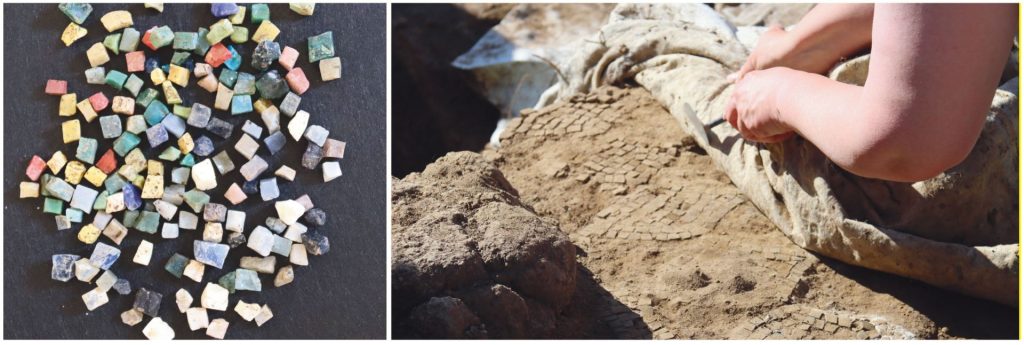

The professors’ original assumption, based on the site’s rural location, that peasants occupied Valle Gianni has also been proved false. Items excavated include more than 500 pieces of mosaic glass, some with gold leaf, and well over a thousand pieces of colorful marble. Among this marble was one important type, giallo antico, which is most often associated with imperial building projects, Cline explained. She and Jasper now speculate the site may have been tied to manufacturing wine, as the area is one of the oldest wine-production regions in the ancient world.

Jasper’s approach blends the study of historical documents and modern datasets of the physical environment to generate hypothetical ancient and medieval landscapes and practices in geographic information system (GIS) databases for analysis. Cline’s interest as an art historian involves determining how the pieces found were used. “It’s essentially two research projects,” she said. Cline studies architectural features and small excavated items, such as lamps dating to the fifth century A.D. and a glass windowpane.

The analysis begins in a lab located near the dig and overseen by Cline. Every piece taken from the ground is documented with meticulous specifics of dimensions and materials. Items are cleaned, labeled, and captured by photography and 3D scans before being prepared for storage. Everything excavated belongs to the Italian government and cannot be removed. A former medieval prison has been converted to a storage center, with the treasures locked in a cell designated for Cline and Jasper.

“Most art history analysis is done with photographs,” Cline said. “But, because we have the privilege of actually excavating and conserving this material ourselves, we aim to do as much with the materials in Italy as possible. This includes working with a conservator and taking various samples for analysis both on- and off-site.”

Stone will assist Cline by analyzing animal bones to provide information about the role of domestic animals in the economy and residents’ diets. The geographers, Kostelnick and Thayn, will use ArcGIS software and LiDAR, ground-penetrating radar technology, to create an extensive map of the area that will help Jasper to provide context for the agriculture activity and trade networks in the region.

“Archaeology is very much a team sport,” Cline said. “We rely on various experts and colleagues to analyze a huge amount of material, all with the goal of making sense of this unknown Roman site.”

This team also includes members from various campuses—including the University of Arizona, Ohio State University, and Wesleyan University—and other collaborators in Italy, England, and the United States. For instance, a conservator with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, along with experts in London, is studying the newly discovered glass windowpane to determine its age and composition.

Cline and Jasper eagerly embrace students on their team as well, including 12 of them in a four-week field school at the site each summer. They quickly learn that while the work seems glamourous, it is difficult. “Archaeology is, by nature, a destructive science. You only get one shot at excavation,” Jasper said. Cline or Jasper often do the extraction of highly sensitive objects so that a student does not bear responsibility for breaking an irreplaceable artifact.

“It’s high stakes,” Cline said.

Combining teaching with research drew Cline and Jasper to Illinois State, which values both equally. “I have a hard time ranking teaching versus research. My teaching has merged with my research,” Jasper said.

They knew of each other’s work but didn’t meet until 2012 when Jasper joined the Department of History and Cline accepted a position in the Wonsook Kim School of Art. The two connected at a new faculty orientation event and upon its completion, walked to an Uptown Normal

cafe where they shared their scholarly plans, which were remarkably aligned.

“Archaeology is very much a team sport. We rely on various experts and colleagues to analyze a huge amount of material, all with the goal of making sense of this unknown Roman site.”

Dr. Lea Cline

“We were both committed to students studying abroad and wanted to lead a dig someday overseas,” Jasper said.

They eventually established a four-week session for students in Orvieto, a community dating to before the Roman era located between Florence and Rome. The dream of overseeing an excavation in Italy was within their reach because both had gained recognition for their academic accomplishments as scholars of Roman and medieval Italy, and owing to their facility in Italian and their experience living and working in Italy.

Cline and Jasper each studied in Italy as Fulbright Fellows, in 2006 and 2008, respectively. Cline did hers while completing her doctorate in art history at the University of Texas in Austin.

A trip to Florence and Rome during Italy’s Jubilee Year in 2000 convinced Cline she wanted to focus her graduate study on Roman art and architecture. Participating in a dig in Italy while a graduate student sealed her decision. “I became passionate about making history physical both for myself and for my students.”

Jasper has been drawn to Roman and medieval Italy since she worked on her first excavation in Tuscany as an undergraduate. She earned a doctorate in history and medieval studies at the University of California-Berkeley, and has worked on archaeological survey and excavation in Arizona and Italy.

Jasper began her career in archaeology before moving into history. “History has something that archaeology doesn’t, in that historians tell stories. I embraced that.” She also engaged in an intense study of Latin that spanned years and resulted in her gaining an international reputation for her expertise in paleography, which is deciphering ancient writing systems.

Both Cline and Jasper have published extensively in their respective fields and are certain their ongoing archaeological work will have an impact. “At the very least, our methodology is important,” said Cline. She envisions publications and presentations on various aspects of the international dig that are exhausting and complicated yet more rewarding than either scholar could have envisioned when they first discussed their mutual ambition to fulfill every archaeologist’s dream.