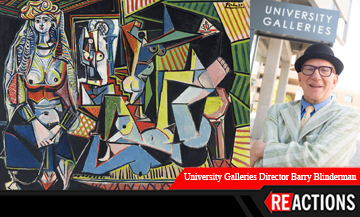

Director of University Galleries Barry Blinderman weighs in on the investment of art and the Picasso painting that sold for $179.4 million at Christie’s Auction House in May.

Blinderman

There is currently a feeding frenzy among collectors worldwide for modern and contemporary art—art from around 1900 to 1950 for modern, and 1950 to the present for contemporary. Even the most contemporary art—work by baby-boom artists—is auctioning for more money relative to works by old masters. Evidently there is more prestige in owning contemporary art, so much that people will pay whatever it takes to get certain pieces. Price is determined by demand. Women of Algiers is one of the few Picassos of this type that was still on the market, so it is considered quite rare. I don’t think whoever bought this Picasso would have paid $179.4 million if they didn’t feel it was a good investment.

Women of Algiers is an exceptional painting by the most famous artist of the 20th century, and probably one of the five artists that people who do not follow art very closely could name. Pablo Picasso’s name is synonymous with artistic ability, as in “He’s a real Picasso.” From the age of 18 onward, Picasso was a restless explorer of all varieties of artistic expression—his progression of styles, from realism to Blue Period, Rose Period, Cubism, and Classical—is etched in most art students’ memories. When the artist was not yet 30, he invented, along with Georges Braque, what we know as Cubism, one of the single most important developments in 20th century art.

Women of Algiers is a fairly late-period Picasso, painted when the artist was in his 70s. It used to be that later Picassos were considered inferior—that his vision was in decline—but these days experts would agree that Picassos of this era are wondrous and important in their own way. They are generally more brightly colored, more brazen than his earlier works. In this painting—one of 15 variations he did in homage to the painting of the same name by Eugene Delacroix—you can see aspects of his earlier work, particularly the period around 1914 known as Synthetic Cubism.

There are plenty of artists, unlike Picasso, whose work goes down in value over time—an artist can be made or broken by one or two powerful collectors either buying them up or dumping them. Art is a gamble, although I think investing in blue-chip art is probably safer than putting your money into most other types of investment. It’s not just that the prices for Picassos are outrageous, the whole secondary (resale) art market is. The most expensive painting ever sold in recent times was a Paul Gauguin, and that went privately for $300 million. So the recent Picasso sale isn’t a record for the most money ever spent on a painting; it’s a record for a painting that was auctioned in public. Next year, the way this is going, some art work will break $200 million at auction.

The thing that owning art “buys” you that cars and houses and islands don’t is the appearance that you have good taste, that a little bit of the artist’s genius has rubbed off on you just by virtue of your possession of their work. I am not for or against the ridiculous amount of inflation in the current art market, but what I am against is the extreme focus on money as opposed to what art is really about—an expression of our experience, a gauge of our thoughts and emotions, our desires and fears. Having too much money circulating in the art market takes the emphasis off these creative aspects and reduces it to a commodity. Art cognoscenti going to museums and galleries these days are more likely to discuss how much a work of art is worth than its aesthetic merit.