It was 150 years ago on December 6, 1865, that Congress ratified the 13th amendment, ending slavery in the United States.

Set against the bloody backdrop of the Civil War and the assassination of a president, Associate Professor of History Touré Reed paints the picture of the road to the 13th amendment, and the legacy that we’ve yet to realize as a nation.

Historians often debate the causes of the Civil War. They look to the existence of slavery; the diverging social, political, and economic goals; or the issue of states’ rights. All those reasons are one and the same, said Reed.

“Northern political economic development was moving in the direction of a liberal, industrial, economic order, built on ‘free labor,’” he said. “The South’s political economy centered on agriculture, where much of the wealth was the product of slave labor.” The emergence of the Republican Party reflected the widening gulf between North and South.

Reed explained that the new Republican party’s anti-slavery platform—in contrast to earlier parties, such as the Liberty Party, the Free Soil Party, and the Know Nothings—rested on a vision of free labor that presumed that working people should have opportunities for mobility. “Because the United States Constitution actually accommodates slavery, the Republicans had little choice but to accept legality of slavery,” said Reed. The party did argue, however, that the Constitution protected the peculiar institution only in the states in which it was already established.

Lincoln and the Republicans called for “containing” slavery—an institution whose profitability hinged on expansion—with the intent of gradually eliminating it. “Republicans of that era ultimately believed that slavery retarded national economic development, degraded/stigmatized work, and imbued slaveholders with despotic temperaments, all of which threatened the fabric of American democracy,” Reed said.

The idea behind the 13th amendment was to not only end slavery, but also to ensure better working conditions for all races.

After the election of the Republican Party’s Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, South Carolina was the first to secede, for reasons that left little doubt that their chief motivation was the defense of slavery, Reed said.

“South Carolina’s justification for commission of high treason could hardly be described as a principled case for ‘states’ rights,’ since one of its chief grievances came down to the non-slaveholding states refusal to comply with federal protections granted to slavery,” said Reed, noting the complaint accuses free states of not following the federal law aimed at protecting the slaveholding states. “South Carolina—much like the states that followed its lead—was clear that its aim was to protect the institution of slavery.”

As the war dragged on, Lincoln set forth the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. “This was a war measure that only ‘set free’ slaves residing in territories that were still engaged in insurrection,” said Reed. Meaning the proclamation did not technically free anyone. “Yet, even though the Emancipation Proclamation would not eliminate slavery in the United States, it was very important, if only because it ensured that for most African Americans the Civil War would be a war of liberation.”

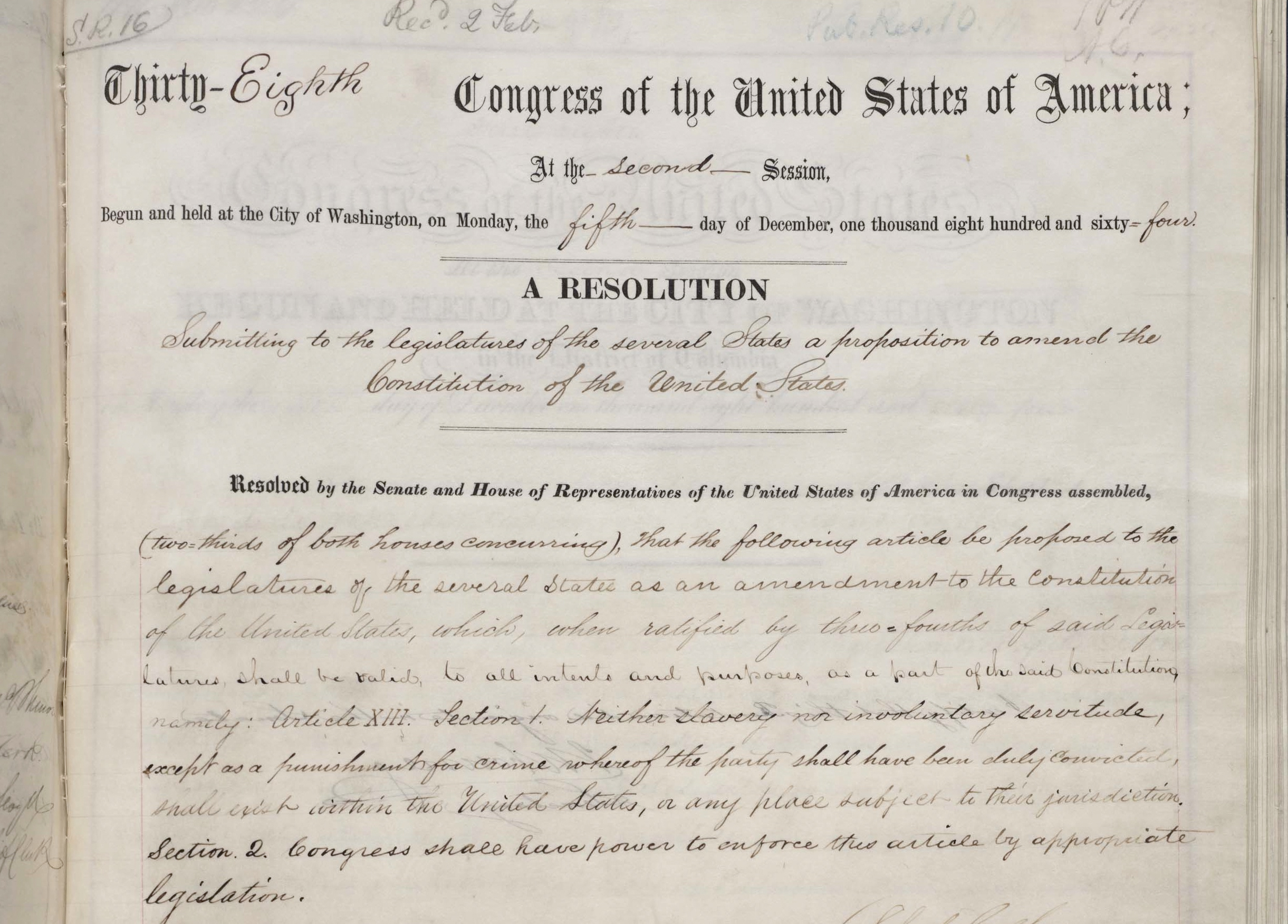

As the war was coming to a close, the North looked to ensure the elimination of slavery in a proposed 13th amendment. The measure passed Congress in January of 1865, and began the process of ratification.

After the war ended, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April of 1865 ensured the amendment would be seen as part of his legacy. Yet it was President Andrew Johnson who guaranteed its ratification by former Confederate states. “Lincoln’s martyrdom was surely an issue in the Northern states that had not yet ratified the 13th amendment, prior to his assassination,” said Reed. “Yet the terms for readmission of rebellious states to the union laid out by President Johnson essentially required that the former Confederate States ratify the 13th amendment.”

Due to the importance of slavery to southern economic life and racism, many southern states refused to ratify the 13th amendment. “It’s worth noting that the last state to ratify the 13th amendment was Mississippi, which did so only in 2013,” he added.

The idea behind the 13th amendment was not only to end slavery, but also to ensure better working conditions for all races. Reed pointed to Sen. Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, who argued during an amendment debate:

“I tell you sir, that the man who is the enemy of the black laboring man

is the enemy of the white laboring man the world over. The same

influences that go to keep down and crush down the rights of the poor,

black man bear down and oppress the poor, white laboring man.”

Yet one piece of the amendment allowed for “involuntary servitude” for those convicted of a crime. That loophole for prison labor continues to support racial disparity, said Reed. “Though different from antebellum slavery in some crucial ways, the current system of convict labor—which has impacted blacks, Latinos, and poor whites disproportionately—reflects the kind of asymmetries in political and economic power that were at the heart of the crop lien and even convict lease, systems labor force exploitation that had begun during Reconstruction and extended into the 20th century,” he said.

Reed considers the passing of the 13th amendment as a great first step, but certainly not the key to racial equality. Though the amendment ended slavery, it did not secure an equal footing for freed slaves or African Americans. “While the 13th amendment was indispensable to establishing a foundation on which black equality could be built, and held great promise for working people irrespective of race, its promise for equality has been unfulfilled,” he said.

Reed can be reached via MediaRelations@IllinoisState.edu.