Taylor Mali can explain why beginning Redbird educators should attend the New Teacher Conference (NTConISU) in just seven words, “Share the sorrow, and feel the pride.”

The acclaimed poet and educator will headline the professional development event to be held 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Friday, June 23, in the State Farm Hall of Business at Illinois State University. The event is open to Illinois State graduates who have taught one to four semesters in the field. The registration fee is $20, which includes lunch, and alumni must register by June 8.

Mali knows the challenges of a beginning teacher because he has lived them. He taught English, history, and math at the middle, high school, and college levels for almost a decade.

If no one else understands why you chose to walk this path, I do, we do, and God bless you and thank you for doing it.

“The first couple years of teaching are incredibly hard. Sometimes the tears you cry at night are a measure that you’re doing it right,” he said. “So drive the hundred-plus miles and come to the conference not just to see me, but to share stories and forge connections that will help ready you for the next step of this rewarding career.”

Now a full-time written and spoken poet (WASP), Mali uses humor and profundity to advocate for teachers. His most well-known slam piece “What Teachers Make” delivers a knockout punch to lazy stereotypes about the profession. In 2012 he completed a 12-year mission to get 1,000 new teachers in the classroom using “poetry, persuasion, and perseverance.” He culminated that effort by donating 12 inches of his hair to the American Cancer Society.

Mali is also a four-time National Poetry Slam champion and author of four books, and was one of the first poets to appear on HBO’s Def Comedy Jam.

While Mali is keeping the details of his NTConISU presentation under wraps, he recently shared a bit about his life on the road, in the classroom, and why he does what he does.

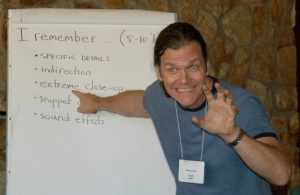

Taylor Mali teaches teachers at a writing workshop.

Why do you like presenting to new teachers?

It’s because nobody enters the teaching profession as a get-rich-quick scheme. In fact, they don’t enter it as a get-rich-slow team scheme, either. They enter it for other reasons, and often those reasons have been belittled their entire lives. What’s most rewarding about the talking to beginning teachers is affirming the reasons they had for wanting to become a teacher in the first place, and to see the relief in their eyes when you validate their decision.

The truth is, sometimes even their parents might have pooh-poohed their dreams. But I get to walk in there loco parentis and say “no.” We all know the path you have chosen to walk is a valuable one. If no one else understands why you chose to walk this path, I do, we do, and God bless you and thank you for doing it.

What’s your approach to talking with teachers?

There’s a hashtag that’s been growing in popularity the last couple of years called #edujoy. For me, the essence of edujoy is this: For all of the challenges that education provides, let’s never lose sight of the joy that the profession provides intrinsically. So I am a high priest in the church of edujoy.

What’s one experience that still sticks with you from your teaching career?

I wrote a poem titled “Like Lily Like Wilson.” On the surface, it’s about a girl who can’t get through a sentence without saying the word “like.” I made my class a like-free zone. Every time any student used the word in that way, they would have to stop, regroup, and say their statement again. I eventually softened my stance a bit, but the important thing was to help them to train themselves to sound articulate.

While Lily was an eighth grader, the actual impetus, the subject of the poem was an undergraduate student from Kansas State University, where I taught an introductory English course as a graduate teaching assistant. I had a student there who said she wanted to write an essay about how gay couples should not be allowed to adopt children. That was a tough one to hear, but I did not let her get the full blast of my liberal, progressive, ponytailed wrath. I just said, “If that’s what you want to write about, go ahead. But remember, you have to find reputable sources to back your argument.”

After two days of research, she came back to me and said that none of the research backed up what she thought she thought. And I said, “What would you like to do about it?” And she said, “I think I would like to change sides.” Those words are a line in the poem. So what the poem is really about is a young woman educating herself to a point where she changes her own mind. That was a victory. It was a huge victory.

Taylor Mali

Why did you decide to become a teacher and a poet?

For me, they are very much connected. When talking about the task of the poet I like to quote the Latin poet Horace. Over 2,000 years ago he said that the task of the poet is either to delight or to instruct, and the best poets can do both at the same time. I wrote an entire one-man show (Teacher! Teacher!) based on the premise that that was also the task of the teacher. Of course the ratio is different as a teacher than as a poet. You are judged on how well you can instruct. But any teacher who mixes a little bit of delight into their instruction knows that it makes the lesson last longer and helps students to think more deeply.

But in a very tangible way poetry and teaching kept leading me back to the other one. I went to Kansas State University to become a better poet, but all graduate students in English were required to teach freshman composition as well. And that’s when I found that I truly loved teaching. It was in my pursuit of poetry that I found I have an equal passion for teaching. In the classroom I saw light bulbs go off over kids’ heads, which is just a wonderful feeling, and I wrote about that. That’s what led me to write the poem “What Teachers Make.” The poem speaks to teachers, and it is indirectly responsible for me quitting my day job as a teacher to see whether I could make poetry a full-time gig. Now I am a full-time poet, but who is it that often asks me to come speak at conferences? Teachers.

What’s one of your most unique experiences as a poet?

I’ll give you two. The most fun that I’ve had reciting any of my poems was while performing a piece I wrote about spellchecking called “The The Impotence of Proofreading.” What’s interesting about it is that I’ve had the opportunity to recite the poem many times alongside American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters whenever individuals who are deaf are in attendance. I don’t know how interpreters do it.

The poem is based off of my past students who ran spellcheck but never proofread their work. There are a lot of misspellings and mismeanings in the poem. For example, “I myself was such a bed spiller once upon a term” instead of “I was such a bad speller once upon a time.” One particular interpreter has performed it with me several times, and she has done it really well. She first signs how the sentence would have read if written correctly, then she signs what I actually said. For me, that is incredibly impressive. When I communicate with people who are deaf they say English is their second language. People who speak ASL, they don’t translate signs into English, first. So the sign for “impotence” and the sign for “important” are completely different. And you can’t expect someone who speaks ASL to see that it’s funny for a person to mean one word, but say the other.

Secondly, in 2013 my Twitter feed blew up because a brilliant artist in Australia who goes by Zen Pencils did a comic book version of “What Teachers Make.” I decided to perform the poem at a conference in Florida with the illustrations in the background. But a graphic novel presenter there convinced me to contact the artist and get the illustrations without words. So I did, and it was a great suggestion. It was one of the most fun experiences I’ve ever had reciting “What Teachers Make.”