Emily Hansen knows farming. “I’m from three generations of farmers,” said Hansen, a second-year Illinois State graduate student from Coal City. “I just sort of grew up in that culture.”

Upon enrolling at Lewis University her freshman year, Hansen put farming aside and chose to study health sciences. But she did advance far into her college career when a soil study introduced her to microbial ecology, and landed her right back on the farm.

“We were comparing agricultural soil and water samples to a natural area and looking at the microorganisms there, and it was sort of like lightbulb for me,” Hansen said. “I thought, ‘I can make my farming stuff way more science-y.’”

Hansen is now pursuing her master’s on the biological sciences track, studying behavior, ecology, evolution, and systematics (BEES). She was drawn to Illinois State after learning about the University’s ongoing involvement in the Integrated Pennycress Research Enabling Farm and Energy Resilience (IPREFER) project.

“When I interviewed here, I wanted to be more involved with the pennycress work, but I don’t have a super-strong molecular background,” Hansen said. “So instead I absorbed an adjacent project and shifted it into the microbial ecology field.”

Her work, which takes place in Dr. Vickie Borowicz’s plant ecology lab, involves collaboration with Dr. Rob Rhykerd, a professor of soil science in the Department of Agriculture whose research focuses on how cover crops–crops planted to protect and enrich soil during the off season–remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and deposit it into the soil. The objective of Hansen’s research is to investigate the impact of cover crops—pennycress included—on soil microbial communities.

Hansen is using three different cover crops in her work: cereal rye; pennycress; and a pea, clover, radish, and oat mix.

“With these different cover crops, how are they changing the microbial community so plants can form beneficial relationships with microbes in the soil?” Hansen said. “And can they help plants uptake nutrients from the soil and cultivate their own microbial communities?”

Her research also involves measuring the diversity of the cover crop soil at varying depths.

“Usually when you take soil samples in an agricultural field, you’ll take the top 6 inches and that’s your sample. But you lose a lot of the smaller variations there; it’s harder to see season-to-season differences,” Hansen said. “Rob had the idea that if we break soil down into 2-centimeter increments, maybe we can see the carbon accumulating in the soil on a smaller time scale. So I’m doing the same thing.”

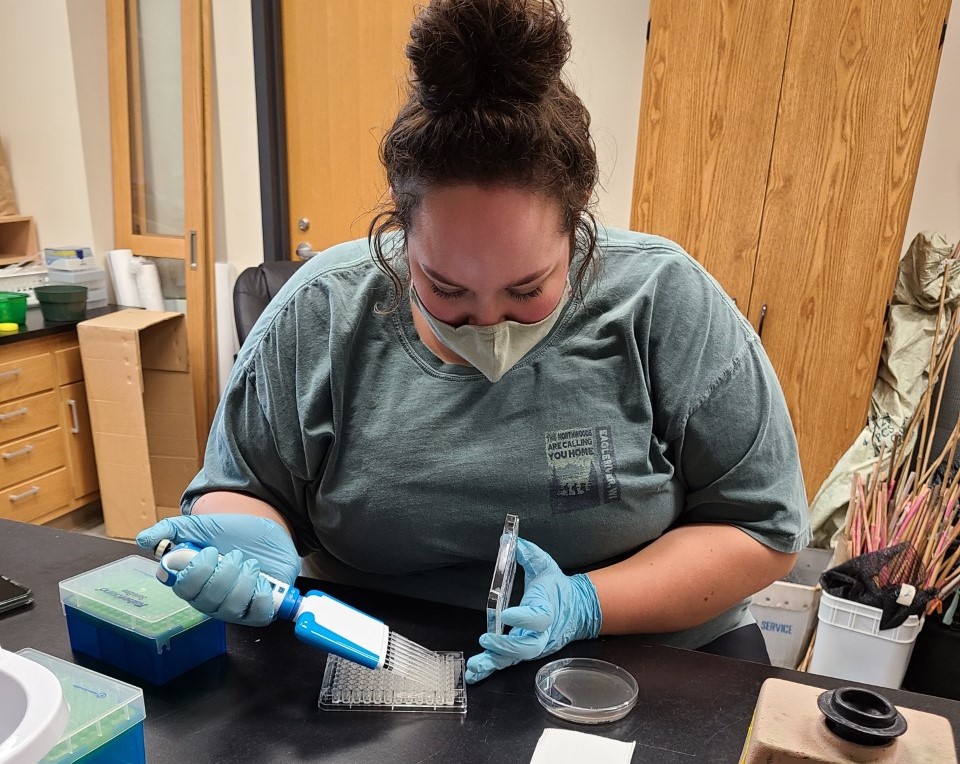

In fall 2021 Hansen pulled soil samples from cover-crop plots at the University Farm at Lexington and measured soil diversity with EcoPlates, multi-well test plates used to incubate soil samples. Current data reveals a strong relationship between depth and diversity, with microbial communities being less diverse deeper in the soil.

The cover crops were then planted for the winter. “Fall samples were for establishing a baseline. When we look again in the spring, hopefully we’ll see some differences between the different cover crops.”

Hansen’s research is funded by the USDA’s Sustainable Agriculture, Research, and Education (SARE) program, which awards grant funding to research and education efforts promoting sustainable agriculture practices. Her use of cover crops in her work is the primary sustainability factor for the research. Planting cover crops and increasing soil diversity eliminate the need for harmful fertilizers, reducing chemical runoff.

Hansen’s goal is to encourage adoption of cover crops by demonstrating the benefits they provide. She plans to foster communication on the subject this spring at University Farm Days–events that bring local farmers to the University Farm to hear about new research in the field.

“It’s a good way to show some students what we do at the farm and all the different research being done there,” Hansen said. “It’s also a great way to show off these things to growers. Farmers will come out and I can show them, ‘Hey, look at how great these cover crops are, here’s all the benefits,’ and from there I hope to get some implementation.”

Hansen hopes to continue her research on cover crops while here. “With cover crops there’s still so much that we could look at. Every time you think you’ve answered one question, five more questions pop up.

“Growing up I always thought, ‘Oh, you know, you plant your corn and harvest it, what else is there to think about?’” Hansen said. “But the more that you learn about agriculture and the more you know, you realize this is still biology.”