From the darkest depths of death and despair, Dr. Theoneste “Theo” Nzaramyimana, M.S. ’17, discovered life in a garden.

As a child, Nzaramyimana and his family fled their home to escape genocide during the Rwandan Civil War. Hundreds of thousands of people perished.

Appears In“I escaped among those who were running away for their lives,” Nzaramyimana said. “We were fleeing to any place we could find. Sometimes entire families were separated.”

Nzaramyimana moved to Zimbabwe where, as a teenager, he met young refugees whose mental health was suffering from traumatic experiences in the war. He wanted to do something for them.

“One way to help was to keep them busy,” Nzaramyimana said. “I ended up engaging with them, helping them grow some vegetables.”

Raised on a farm in Rwanda, Nzaramyimana constructed a roughly 10-by-10-foot garden plot in a Zimbabwean refugee camp. He helped a group of kids there learn how to grow amaranth (pig weed), kale, cabbage, tomatoes, green beans, and sugar beans.

They kept their plants well-watered in the hot and dry climate, fertilized them with cow manure, and protected the plot with thorns to discourage elephants, antelopes, and deer from eating their freshly grown produce. The vegetables were a necessary addition to the refugees’ diet of cornmeal and rice provided by the World Food Program.

“We were donating most of the produce, and we ate the extra,” Nzaramyimana said. “For me, it was about engaging with the kids and helping those vulnerable and elderly people who could not do the work.”

“When you’re growing food with kids or students, you’re cultivating communication, self-esteem, motivation, time management, and teamwork.”

—Dr. Theoneste “Theo” Nzaramyimana, M.S. ’17

In his small, educational garden, Nzaramyimana made a profound discovery. Growing food created an impact far greater than the vegetables’ nutritional value.

“It’s not just about harvesting what you eat,” he said. “When you’re growing food with kids or students, you’re cultivating communication, self-esteem, motivation, time management, and teamwork.

“When a kid sees a tomato plant growing and they pick the tomato and they taste the tomato, that is really powerful because they have ownership. They saw it growing and they say, ‘I did this! I’m the one who grew this!’”

While managing the garden, Nzaramyimana taught himself high school-level curriculum. He then applied and was admitted to Africa University in Zimbabwe, where he received a scholarship to study horticulture. As a college student, he volunteered at a nearby youth center.

“I was there to teach them farming skills,” Nzaramyimana said. “A few kids who had been living on the streets were able to start raising chickens and growing vegetables to sell in order to go back to school. It was a great thing. With that, I knew there was nothing I wanted to do more than agriculture.”

Nzaramyimana applied for a study-abroad internship in the U.S. By chance, he was placed with Todd ’94 and Joanna Wright, who manage a 6,000-acre farm in rural Bradford, 35 miles north of Peoria.

A graduate of Illinois State University’s Department of Agriculture, Todd took Nzaramyimana on a visit to Illinois State where they met several faculty members, including Dr. David Kopsell, a professor of horticulture.

“The Wrights recognized how intelligent Theo was and just what a fantastic person he is,” Kopsell said. “I told them, ‘If you can get him here, we’ll have a project for him.’ And it worked out.”

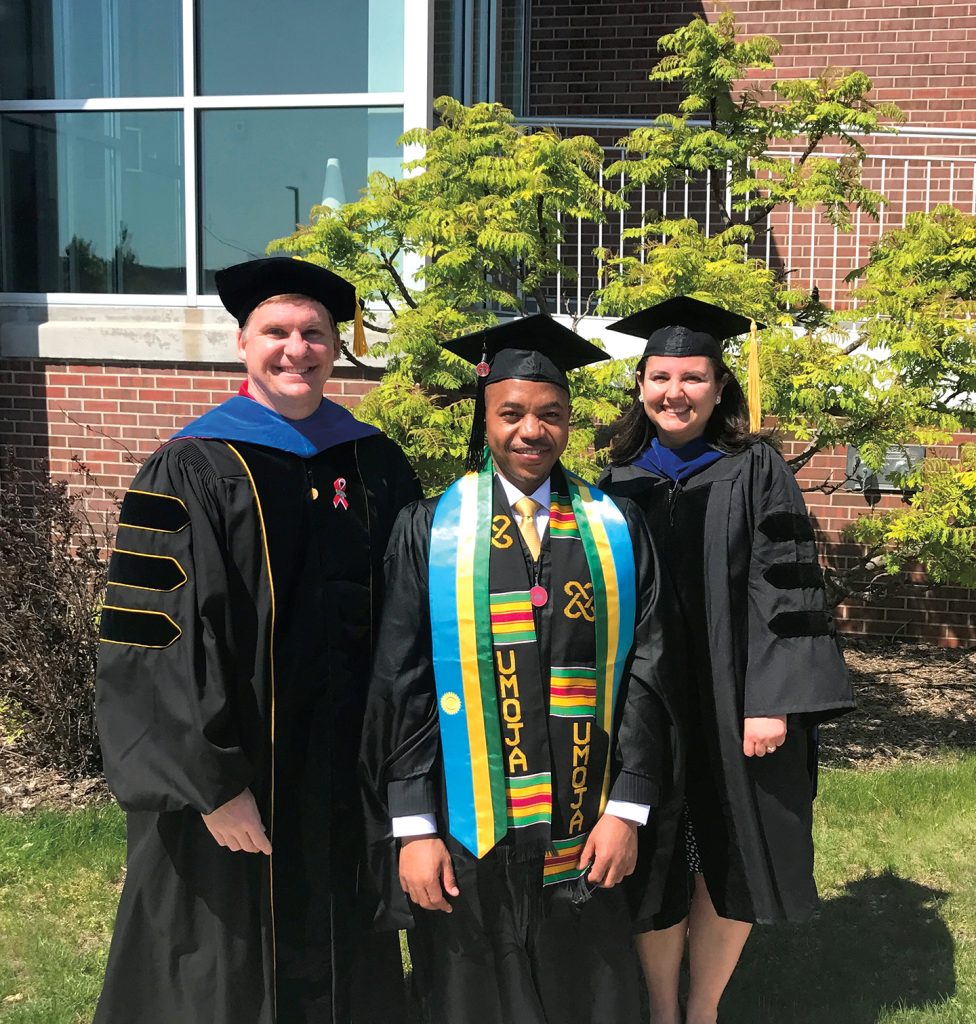

A year later, Nzaramyimana began working toward a master’s in agriculture science at Illinois State. Kopsell was his advisor.

“Dr. Kopsell was instrumental,” Nzaramyimana said. “My writing was not that great. My first paper was extremely red (with Kopsell’s ink) when he reviewed my proposal. I was like, ‘I think I need to quit and go back because this isn’t for me.’ And he said, ‘Don’t worry. You are here to learn.’ He kept revising my drafts, and I built up a topic and started really learning.”

Nzaramyimana connected with everyone in the department and willingly shared his personal story. While excelling in graduate school, Nzaramyimana also volunteered at the Unity Community Center in Normal where he helped underserved kids with their homework and planted a community garden.

“Theo is probably one of the most genuine individuals I’ve ever met,” Kopsell said. “You can tell that tragedy has kind of shaped who he is. I think it’s caused him to view life as being very special, and he shares his talents with as many people as he can.”

For his graduate thesis, Nzaramyimana hydroponically (using a water-based nutrient solution rather than soil) grew edamame in a greenhouse and manipulated the sulfur fertility to alter the vegetable’s bitterness.

“He did really well with that project, and I told him he should go for a Ph.D. because he had that much talent and was that intelligent,” Kopsell said.

After graduating from Illinois State in 2017, Nzaramyimana pursued a doctorate at Purdue University. By then, he was married to a woman he met in Zimbabwe, and the couple had a son.

“(Working toward a Ph.D.) was extremely intense,” Nzaramyimana said. “But I give credit to my wife who always says, ‘Whatever’s in your heart, go for it. I’m there to back you up.’”

For his dissertation, Nzaramyimana co-initiated a program in Indianapolis where he worked with inner-city youth to develop urban agricultural skills and entrepreneurship opportunities.

He graduated from Purdue in 2020 and became a faculty lecturer. In January 2023, he started his current role as an assistant professor for urban agriculture at Kentucky State University, a historically Black university (HBCU), in Frankfort, Kentucky.

Nzaramyimana said urban ag provides an effective solution for food inequity in underserved communities.

“A lot of community gardens and youth programs are born because of activists’ visions,” he said. “They want equal opportunity for fresh produce in different parts of cities.”

This can be accomplished through urban ag, which includes rooftop farming, vertical farming, greenhouses, and Freight Farms—hydroponic farming systems in retrofitted shipping containers.

“When students interested in ag see a greenhouse or a Freight Farm, they see it’s a great opportunity because they can do it too,” Nzaramyimana said. “It’s really expensive to purchase farmland. But they can own a small greenhouse in a backyard. So, we’re starting to see kids from the city joining urban ag programs.”

Kopsell is in the process of co-developing a cross-disciplinary Sustainable Urban Agriculture class at Illinois State funded by a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant. Nzaramyimana is on the course advisory panel. Plans to install a Freight Farm on Illinois State’s campus are underway.

“Getting this life—it’s just a miracle.”

—Dr. Theoneste “Theo” Nzaramyimana, M.S. ’17

Not only can urban ag improve food access, but growers can produce culturally relevant food for their customers, according to Nzaramyimana. He focused on serving immigrant populations during a class he started at Purdue called Ethnic Crops.

“(Immigrant populations) need the food that they used to eat back home,” Nzaramyimana said. “They need that traditional, culturally relevant food.”

Nzaramyimana understands the power of food firsthand. He and his wife would drive 90 minutes from Purdue’s campus to Indianapolis to buy African eggplants.

“It’s not just food. It takes you back home. It connects you to your home country,” he said.

Nzaramyimana predicts exponential growth in urban ag during the coming years, and he will be at the forefront as one of just a handful of professors in the country currently focused on the specialized area of horticulture.

Now the father of three young boys who enjoy helping their dad grow tomatoes in backyard containers, Nzaramyimana is “thankful” for how he’s grown personally—from surviving a tragic childhood to becoming an impactful educator and mentor dedicated to helping his students blossom.

“Many people lost their lives in the war. There are many people who never got what I got,” Nzaramyimana said. “Getting this life—it’s just a miracle.”