Native American culture is alive and illuminating. A new course from Dr. Shannon Epplett explores the arts and ideas of current Indigenous artists.

“The idea is to bring culture hiding in plain sight and make these artists visible,” said Epplett, an instructional assistant professor of theatre at Illinois State University. He began teaching the theatre class “We Are Still Here: Native American Popular Culture” in the spring of 2022. “People often dismiss Native American culture as historical, or traditional, as something that only exists in the past. This class is about looking at the work that is created by and for Indigenous people today, to make Native America visible and present for non-Natives.”

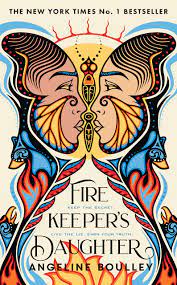

An enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Epplett drew from tribal members for some of the course materials, including Angeline Boulley’s young adult novel The Firekeeper’s Daughter. Released in 2021, the book is set in Sault Ste. Marie, in Michigan’s upper peninsula. Epplett knows the area well as his maternal family is from “the Sault,” going back at least seven generations. “Growing up, I spent every summer and holiday in ‘the Soo,’ and Boulley really captures the place in writing,” he said. “A sense of place, the land, is really significant in Native American culture.” Epplett noted his tribe members were not removed from their land in the same way that other Native Americans were displaced. “Rather we were assigned to allotments of land in the area. So, we still live in our traditional environment.”

As they dive into media, students also glean the basics of the culture, belief systems, and the names of the people. “Our tribe is called both Chippewa or Ojibwe, which are both renditions of the same term,” said Epplett. Europeans adopted the name another tribe used to describe them, referring to the way they made their moccasins. “Ojibwe is how it was rendered by French speakers. Chippewa is how it was rendered in English,” he said. “Anishinaabe is the term we apply to ourselves, it roughly means ‘breath in body,’ ‘spirit in flesh,’ or simply ‘the people.’ Officially my tribe is called the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, but other tribes say Ojibwe or Anishinaabe.”

Some things need to be felt in order to be understood. Art does that. It instills empathy and understanding.

Dr. Shannon Epplett

Fire Keeper’s Daughter, which features a teen Anishinaabe girl often compared to an “Ojibwe Nancy Drew,” provides students a potentially new perspective in storytelling. “It’s really cool to see a place you know so well depicted in a book or film, and to see it portrayed in a distinctly Native way, from an Indigenous point of view,” said Epplett. Other tribal sources include Edward Benton-Benai’s The Mishomis Book and the 2016 independent film INAATE/SE by Adam and Zach Khalil. “The film is a reimagining of the Seven Fires prophecies as they appear in Benton-Benai’s book, and is filmed in Sault Ste. Marie,” he said.

For the course, Epplett aimed to include works to which students could connect. “They related to the young people in the TV show Reservation Dogs, which is about Indigenous teens in Oklahoma. It also helped that they recognized co-director Taika Waititi from directing and acting in Marvel films,” Epplett said. He added that many students also connected with Tracey Deer’s 2021 movie Beans. The film follows a Mohawk girl during the 1990 Oka Crisis in Quebec. “We hardly know of the Oka Crisis, but everyone has been 12 or 13 years old, had a first crush, and tried rebelling against their parents by staying out late or hanging out with the ‘bad kids,’” he said. “These are the things the main character is experiencing, set against the backdrop of a violent standoff over land between Native people and the Canadian military.”

The course also explores Native Americans making music, like the The Halluci-Nation, John Trudell, Tanya Tagaq, DJ Shub, and Snotty Nose Rez Kids; producing social media, like Comedian Tonia Jo Hall’s “Auntie Beachress” character and The 1491s; and creating visual arts, such as Cannupa Hanska Luger, Kent Monkman, and Wendy Red Star.

The exposure to Indigenous culture is even more vital in places like Illinois, Epplett noted. “It’s especially important in a state like Illinois to show Native people as living and present,” he said. “Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio were cleared of Native Americans in the 19th century. There are no reservations or Native communities here as there are in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Chicago’s urban Native community was created by the Relocation Act of 1956, moving Indians off the reservation and into the city, hoping we’d assimilate. So, in Illinois, Native Americans are especially invisible, outside of sports mascots and place names.”

Though Epplett said his original intention was to try and avoid the “sad Indian narrative,” he quickly realized to celebrate the artists and the art meant walking with all of the stories. “I don’t teach the class from the perspective of history or trauma. It is about the art Native people make now,” he said. “Trauma, history, identity inevitably play into that, but the focus of the course is to appreciate the story, enjoy the film, and look at the work aesthetically.”

“Art and artists bring another dimension to understanding,” said Epplett. “You can read all the anthropology and history and political theory there is, but I think some things need to be felt in order to be understood. Art does that. It instills empathy and understanding.”