Mennonite College of Nursing (MCN) marks its centennial year having achieved a level of excellence and energy that belies the struggle behind its founding. From its start as a Sanitarium Training School in Bloomington to its national status today at Illinois State, the educational endeavor has required extraordinary courage and commitment.

The beginnings trace back to Emanuel Troyer, a humble Central Illinois Mennonite pastor. While raising funds to establish a school in 1919, he could never have envisioned the college as it stands today with graduate programs, million-dollar research initiatives, high-tech lab equipment, and students who consistently pass the profession’s standardized test far above state and national averages.

Appears InTroyer’s goal 100 years ago was to see the Mennonite Church extend its Christian outreach by establishing a hospital and training nurses. It took work convincing congregations of farmers to financially support the idea, but enough funds were acquired to purchase a home for $10,000 in Bloomington. Converted for hospital care, the first patients arrived in May of 1919.

Expansion into education came quickly with an offer from physician George Kelso, who was ready to sell his Bloomington sanitarium for $75,000. Troyer and four others struck a deal “without a dollar in the treasury to pay for it,” according to Troyer’s personal writings. As a result, the Mennonite Sanitarium Training School opened with 11 students in May of 1920.

“The situation was so acute,” Troyer stated, “that for two whole nights I rolled and tossed, until finally it was just like a voice that said ‘The problem is more mine than yours.’” This brought a peace to Troyer, who repeatedly stated “This is of God—it will succeed.”

The decades since have proven Troyer’s prophecy true, as the college has flourished beyond expectations while remaining grounded in its Mennonite roots. Two decades after the school’s two-year diploma program started, Mennonite Hospital School of Nursing was established.

The school advanced with financial support from Mennonite Hospital. Academic offerings steadily expanded and by the 1980s, a baccalaureate curriculum was approved. The paradigm shift from a diploma to a degree program was significant, as Mennonite blazed a new trail in nursing education.

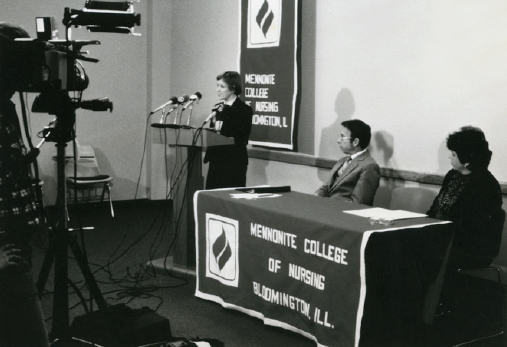

“We were establishing a college. The enormity of that undertaking! We were making history,” said Kathleen Hogan, who served as founding dean when MCN was formed in December of 1982. She went on to become president in 1990.

It was under Hogan’s watch that the college received accreditation from the North Central Association in 1986, with the endorsement from the National League for Nursing acquired in 1987. The credential was retroactive to the first baccalaureate class in 1985, which was the same year the last class of diploma students graduated.

Mennonite was consequently the first independent, upper-division, single-purpose, degree-granting nursing institution in the entire country. The milestone elevated MCN to a new level from which the college advanced further. Scholarships were initiated, enrollments grew to consecutive records, and graduate programs were added.

“We never planned to stop at the baccalaureate level,” Hogan said. “We went right into developing a graduate program. Our 10-year strategic plan included the framework for a doctoral program.”

There were obstacles to overcome in pursuing that goal, with finances the greatest hurdle. Hogan was at the helm when the college’s viability under BroMenn Healthcare became a concern. Medicare funds used by BroMenn to support the college’s $3 million annual budget were dwindling. The situation was so critical that the college had to explore aligning with an existing institution of higher education or face closure.

A proposal from Illinois State was deemed the best fit. The possibility of uniting was pursued by Hogan and ISU President David Strand, with leadership teams from both institutions partnering. Hogan worked to guarantee the Mennonite legacy would continue. Strand enlisted Illinois legislators—Sen. John Maitland Jr. and Rep. Bill Brady—to acquire $1.2 million in state funding needed for the University to finance the college.

The efforts were rewarded with Mennonite College of Nursing at Illinois State University welcomed to campus on July 1, 1999. It was the first private/public higher education merger in the state. ISU acquired a sixth college, and its first professional program. MCN gained financial stability and a world of opportunity with greater teaching resources once settled into Edwards Hall, which underwent a $1.5 million renovation.

There was also a responsibility to intensify a research agenda, while maintaining the fundamental goal of preparing the next generation of caring and competent nurses. The effort to reach both objectives was led by Nancy Ridenour as the college’s first dean at ISU, followed by interim dean Sara Campbell ’86, M.S. ’93. Janet Krejci took the helm in 2009, with H. Catherine Miller serving as interim prior to the arrival of Judy Neubrander in 2016.

As the current dean, Neubrander expresses gratitude to all of her predecessors for collectively creating an exceptional college. “I am blessed by all who went before me the past 100 years,” she said, acknowledging the excellence that has continued throughout Mennonite’s history.

There is ample evidence of reason to boast of all accomplished, including within the 20 years since MCN joined ISU. The college has invested more than $2 million to create a simulation lab that provides a virtual hospital unit. Students learn by working through nursing scenarios that build critical thinking skills and confidence.

Federal external funding totaling millions has resulted in programs focusing on specific aspects of nursing, from training nurses for geriatric care to addressing needs of rural populations and recruiting underrepresented groups to the profession. Community outreach has intensified, with students working beyond hospitals and nursing homes. They are also active in local schools through America’s Promise, which counts as clinical hours for the students as they work to improve the health of children.

MCN students train abroad as well through an ongoing transcultural nursing program. It is one of many expanded academic opportunities, as the college has added doctoral degree programs, accelerated learning options, and a path for registered nurses to complete a bachelor’s degree in nursing.

U.S. News & World Report ranks Mennonite College of Nursing as having one of the country’s best graduate schools, and scores it among the best national online bachelor’s and graduate programs as well.

Given its reputation, it is not surprising student demand is strong. The College is exploring strategic growth where feasible, however, finding additional sites to place students is an obstacle. This is one reason the college’s focus for growing enrollment is in the area of graduate studies and the opportunity for registered nurses to complete an undergraduate degree online. Dual enrollment with community colleges is an option MCN is implementing. Neubrander is also exploring how to expand the simulation lab options as a means for students to complete more required clinical hours.

Regardless of how nurses are prepared, the need to recruit and retain faculty with a master’s or doctorate is a second obstacle as the college goes forward. “As a part of succession planning, we anticipate future retirements within the next few years,” Neubrander said, adding that it is a challenge to entice nurses into pursuing the path of an educator in the field.

Neubrander is confident those who join the faculty in the future will take research a step further by securing more government grants. Work is needed in areas of how to care for patients outside the hospital, which is the direction of health care. She would like to see more done to prepare students to work with geriatric patients, who often have complicated care needs, and is eager to see the college focus on further developing a mental health track.

Efforts to increase private giving are another priority for Neubrander. She is pleased to know the University continues to have within its master plan the building of a facility for the college, but is realistic in knowing such a structure is in the distant future.

Neubrander’s focus is consequently on more immediate issues of ensuring students are prepared to make a difference at the bedside of their patients as a nurse with a fantastic skill set who is equally attentive to the holistic care of the individual. Teaching this critically important mix has been fundamental throughout the past century.

“We have such a rich history that has made us who we are,” said Neubrander, who is as committed as her predecessors to making certain each graduate enters the field with compassion, competence, confidence, commitment and conscience.

That has been—and remains—the Mennonite way of preparing nurses.